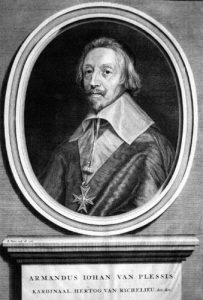

The reintegration policy led by Richelieu from 1630 to 1642

The Alès peace treaty (and the Edict of Nîmes) of 1629 had deprived the Protestants of their strongholds and put an end to their political power. The Catholic worship was re-established in the Reformed cities : Montauban, Nîmes, Castres… and the Protestants had to finance the Catholic Church in compliance with the Edict of Nantes.

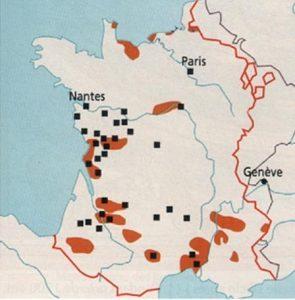

Changes occurred in the Protestant areas with the arrival of Catholic peasants, craftsmen and workers (Montauban, La Rochelle). The Catholic notables followed with their servants. From 1632 onwards, the Parliament in Toulouse required the Protestant towns of Montauban and Castres among others, to provide equal representation for Catholics and Protestants.

On the other hand, Richelieu strove to get the “heretic dissidents” to convert to the Catholic faith. He considered religious unity as the cement of political unity. Richelieu thought that by a re-centring of the Catholic Church on its “true doctrine” the theological disputes between Catholics and Protestants could be lessened. This project of reunion in a new Catholic Church roused opposition from the Reformed synods and Rome as well.

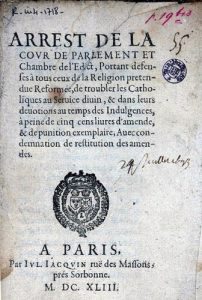

Legal restrictions

Legal restrictions were often taken by Parliaments, which were often under the influence of the Catholic religious organisation : “la Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement”. Their main aims were the suppression of Protestant places of worship or the closing down of schools for violating the Edict of Nantes. A royal statement of 1634 forbade pastors from worshipping outside their place of residence : as a result, secondary temples could not be used as places of worship.

From 1635 on, the clergy assemblies made up of bishops and abbey delegates, which met with the king every five years, started presenting complaints against the Huguenots in order to obtain a stricter enforcement of the Edict.

In 1640, a decree of the king’s council required that processions of the Holy Sacrament should be greeted when passing, under penalty of a hefty fine.

However, the foreign policy led by Richelieu against the Hapsburgs during the Thirty-Year War received support from the Protestant princes of the German Empire. Consequently, Richelieu overlooked the “crackdown on heresy”.

A lull with Mazarin

In 1643, when Louis XIII died, his son Louis XIV became king. He was five years old : Anne of Austria, the queen mother, was in charge of the regency. Cardinal Mazarin carried on Richelieu’s foreign policy against the Emperor Ferdinand III (until the Westphalia treaty in 1648) and against Spain. He was allied with the Protestant German princes and England. It was important for the security of the State to satisfy these allies. Consequently, the French Protestants were no longer legally harassed.

Many decrees of the king’s council even overturned previous decisions meant to limit the impact of the Edict of Nantes. On account of his leniency, Mazarin was said not to be eager to defend the Church.

However, the Catholics gained ground and even created new dioceses : in 1648, La Rochelle became an Episcopal see.

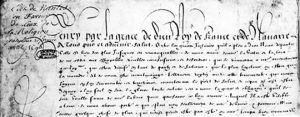

During the events of “La Fronde” from 1649 to 1653, the Protestants remained faithful to the king. The royal declaration of 1652, signed by Louis XIV when he came of age, solemnly confirmed the Edict of Nantes while praising the members of the Reformed Church for their faithfulness and kindness during the period of unrest.

During this period of religious peace, Protestantism regained ground : the members of the Reformed Church rebuilt the temples that had been pulled down and even built new ones. But in 1659, the academy of Montauban (Reformed theological school) was exiled to Puylaurens, a small remote village in the Tarn and the Protestant school in Montauban went into the hands of the Jesuits.

The Catholic response

As the Protestants gained ground, the clergy assembly reacted and in 1655 required the revocation of the declaration of 1652 as well as the destruction of the temples and revocation of the decisions limiting access to religious services.

Mazarin accepted, and the royal declaration of 1656 proved more restrictive than that of 1652. However, the national synod of the Reformed Churches was still allowed in Loundun in 1659 but was to be the last one.

The Pyrenees peace treaty signed with Spain in 1659 allowed even more restrictive measures against the members of the Reformed Church. This led to the “edict of rigor”.