A province not to be antagonized

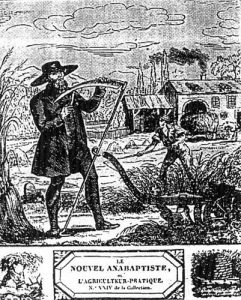

The coercive policy carried out against Protestants was relaxed towards the end of the 17th century. The Treaty of Ryswick (1698) put an end to the disastrous war of the “Augsburg League”. France lost parts of its previous conquests, with the exception of Strasburg, and confirmed some of the liberties theoretically granted in 1648. However, the Treaties of Utrecht (1713) and Rastatt (1714) followed the belated French victories, thus putting an end to the War ofSpanish Succession and granting France the entirepossession of Alsace.

The generally accepted idea was that this frontier province, a likely field of future conflicts, was not to be harassed. Orders to that effect were given by the Duke of Orleans, Regent after the death of Louis XIV. Though King Louis XV, on attaining majority, announced his intention to maintain the Edict of Fontainebleau (The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes), it did not concern Alsace, since its freedom was guaranteed by the previously signed international treaties. Emigration was likewise authorised, but without the usual payment of a heavy tax.

Tolerance towards the Protestant community

From 1727 onwards, a true status was granted to the Protestant community. But the fact that all Protestant ministers – and the Catholic clergy likewise – had to be French nationals, inevitably created difficulties for the Protestants since numerous ministers came from the German Empire. As a result, a career in the Church was encouraged in numerous Protestant families. This had the added advantage the people were closer to their new, locally-born ministers.

“Regard and deference” for the king’s religion were requested from the Protestants, whose religion he tolerated. Naturally, the local authorities did not always hold such a conciliatory attitude towards the government, especially concerning the denominational adherence of children born of new converts, or the enforcing of the simultaneum regulations causing numerous local conflicts. Nevertheless, in 1762, the Duke of Choiseul wrote that « His Majesty’s intention is that all his subjects, without distinction, be treated with justice and humanity ». The suppression of the Jesuit Order in 1764 appeased the Protestant community. Besides, the Alsatians welcomed the economic prosperity brought by reforms carried out by the central power. The construction of huge administrative buildings, of the Palais des Rohan and the Chapitre Saint Thomas are good examples of this.

The Maréchal de Saxe

The funeral in Strasburg of Maréchal de Saxe (1696-1750) bears witness to these improvements. A victorious soldier, the Maréchal had always remained a Lutheran : he could not, therefore, be buried in a Catholic church, and there were no more official Protestant churches left in France. As there were established Lutheran churches in Alsace, Court officials requested their assistance in organising the funeral ceremonies. On 8 February 1751, a grandiose procession followed the coffin to the Temple Neuf in Strasburg, where all the civilian and military authorities had met ; the event caused a great stir, as it showed that Protestantism was officially recognised. The union of Alsace with France was making good progress: in 1773, the remains of Maréchal de Saxe were buried in the Strasburg Lutheran church of St Thomas where Pigalle was commissioned by King Louis XV to build a splendid mausoleum. The ceremony was held exclusively in French.