A free-spirited Cévenol Protestant

André Chamson (Nîmes, 6 June 1900 – Paris, 9 November 1983) was of Protestant lineage and grew up in his native Cévennes where he often located most of his novels after writing his thesis about his region. He went to school in Le Vigan and Alès, and then went to Paris in 1918 to prepare for the competitive exam for the Ecole Nationale desChartes. While studying at the Sorbonne University he created the French branch of the ‘Vorticicts’, a modernist movement inspired by symbolism and cubism. In 1922 he met Lucie Mazauric (Anduze, 20 August 1900 – Paris, 9 June 1983), a Protestant from the same Ecole des Chartes. They married in 1924. In 1927 their daughter Frédérique was born and named in homage to the writer Frédéric Mistral. She became a writer and an actress under the name Frédérique Hébrard.

A committed young man

In 1925, André Chamson published his first novel Roux the Bandit in which he shows his pacifist convictions. In 1926 he was employed at the National Library, and chosen as deputy chief of staff for Edouard Daladier, minister of Public Education. That same year, Lucie Chamson-Mazauric started work as an archivist and librarian at the Louvre museum where she stayed until she retired in 1965. In 1933, André Chamson was appointed assistant-curator at the Château de Versailles.

He became a prominent figure among committed intellectuals; he supported the Popular Front in the 1930s, and was part of the Vigilance committee of Antifascist Intellectuals created after the events of 6 February, 1934. In 1935 he founded the weekly newspaper Vendredi with intellectuals ranging from André Gide to Jacques Maritain, also with Jean Cassou, Jean Giono, Paul Nizan; Lucie Mazauric wrote articles on art for it. Vendredi was suspended in late 1938 though it was a popular success – 100,000 copies were rapidly being printed – and supported the left wing in 1936.

In the turmoil

After supporting the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, André Chamson was mobilized as captain in the Chasseurs Alpins when WWII broke out. In August 1939 the Louvre was closed and the mobilisable staff was enrolled, while the missing non-mobilisable staff was called back to start withdrawing the collections. Thus did Lucie Chamson help transfer works to different places, as far as the abbey of Loc-Dieu, in the southern part of Aveyron, on the edge of the Lot and Tarn-et-Garonne.

After he was demobilized, André Chamson joined his wife and his daughter there. His commitment to Vendredi and to the Republican Spanish cause, as well as his anti-fascism explain why he was not called back by the hierarchy as curator of the museum in Versailles, at the time. Jacques Jaujard was head of the national museums and hired him as project manager in Loc-Dieu and then in Montauban, when paintings from the Louvre were transferred there from September 1940 onwards. André Chamson met René Huyghe again, then head of the paintings department at the Louvre and in charge of the Montauban store: Chamson was his assistant until 1945.

True to his convictions

Chamson was very much affected by France’s defeat, and refused to publish his work while the country was occupied. It did not prevent him from writing, but, as he was overseen by the Vichy police, he hid his writings in a hollow tree.

Of his stay in Montauban the inhabitants remembered his dark novel The Miracles Well describing everyday life and its darker sides under the Occupation. When it was published in 1945 Chamson explained: ‘I admit that The Miracles Well is one of the novels describing the shameful times, but it is mainly about having confidence in man’s indestructibility. From my first book until those I could write tomorrow, I never wrote but as a witness to that’. To that statement should be added the very beautiful and touching Written in 1940: ‘I write for the day of liberty. I write to ward off the evils of the defeat…’ in which he shows his love for the region and the city he then considers ‘a second small homeland’.

He formed ties, and friendships were forged, as was the case with a small community of intellectuals who shared a similar ideal. Besides some resistants, two Protestant women can be mentioned: the first, Elisabeth Schmidt, was the first woman to become a pastor for the French Reformed Church, and the second was her sister Simone, a doctor involved in the Resistance and recognised as ‘Righteous Among the Nations’.

André Chamson tried to exfiltrate an Austrian Jewish couple (called ‘Mister from Vienna’ in The Miracles Well) to his home in the Cévennes. They lived in the same building as he did, but they were rounded up just before leaving for freedom.

In 1943, the events compelled the people in charge of the collections to find new shelters. After some mishaps, the collections were moved in early April and the Chamson couple ended up at the La Treyne store in the Lot. Chamson’s Resistant name was Lauter, and he was connected with the Lot maquis; with André Malraux, he had met before the war, he took part in fighting with the Alsace-Lorraine brigade to free the land.

Public recognition

After the war, André Chamson was appointed curator of the Petit Palais museum – he was also elected president of the Pen Club en 1956. Besides, he served as a board member of the ORTF (T.N.Office de Radio-Télévision Française). In 1959, André Malraux offered him the Direction des Archives de France. In 1964, André Chamson created the store in Espeyran (Gard); and also the store for Overseas archives in Aix-en -Provence, as well as the contemporary archives of ministries and of central administrations in Fontainebleau.

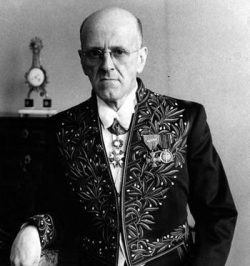

As early as 1936 the idea of applying for the Académie française was brought up by Paul Valéry, but André Chamson was elected in 1956 to the baron de Seillière’s seat, notably with the votes of Jules Romains, André Maurois and Georges Duhamel.

Faithful to Protestantism

André Chamson died a few months after his wife. His funeral took place at the Temple de l’Oratoire in Paris. They are both buried in the Cévennes, in the heart of nature, at the Col de la Lusette: on their grave is engraved, in facsimile, the word « Resister » de la Tour de Constance.

Chamson’s written work is largely marked by his love of the Cévennes and inspired, in large part, by his attachment to the memory and history of his Huguenot ancestors: Roux le bandit, L’Aigoual, Les Hommes de la route, Le Crime des justes, La Tour de Constance, to name but a few.