His first literary works

In 1891, Gide published Les Cahiers d’André Walter ; in this story Walter was in fact his alterego. From the start it caught the attention of many well-known figures of the time, including Maurice Barrès, José-Marie de Hérédia and especially the leading element of the Symbolist School, Stéphane Mallarmé.

From this moment, Gide was considered to be a writer of quality.

He also travelled with friends ; his first stay in Algeria (1893-1894) fired his imagination and it was here that he gave free rein to his homosexuality and also met Oscar Wilde for the second time, having been previously introduced to him in 1891.

His mother died in 1895 ; although she had always cared for him well, her parental authority had been somewhat suffocating ; some months later he married his first cousin Madeleine Rondeaux (1867-1938).

This “marriage of convenience” which André had considered to be a desirable choice since his adolescence, may not have been successful in the terms of a traditional marriage, nevertheless it provided the stability he needed, giving him an emotional and moral base when he was torn between conflicting passions.

In 1897 Gide published Les Nourritures Terrestres, one of most famous works. He advocated the refusal of any kind of moral constraint, the pursuit of pleasure, the importance of happiness as an end in itself. It was a kind of hedonistic treatise which immediately had a strong influence on his generation and its popularity has never waned with time.

His following works fell into two categories : the first being very puritan, for example La Porte Etroite, a fictitious story which used elements from his own marriage and its failure (1909), La Symphonie Pastorale (1919), which was successfully brought to the screen by the producer Jean Delannoy with a pastor in the leading role. The second category was frankly sensual, for example L’Immoraliste, Les Caves du Vatican (1914), in which total amorality was openly advocated. Si le Grain ne meurt, which was published in 1920, was a kind of autobiography of his youth. In this work he criticized his protestant upbringing with scathing reality.

In 1924, he published Corydon, a moderately convincing defence of homosexuality which met with a violent reaction from his catholic friends, then Les Faux Monnayeurs (1925), his most ambitious novel.

Gide’s dramatic works met with some opposition : Le Roi Candaule, (1901), was only performed once – this was followed by Oedipe in 1931 and finally Thésée, a kind of literary testament, in 1946.

Gide was also a literary mentor at the beginning of the century, when there were so many talented writers. He was a co-founder of La Nouvelle Revue Française, which came out in November 1908. Many writers who were also his friends contributed to this publication : Paul Claudel, Jean Schlumberger, Roger Martindu Gard, Francis Jammes, Paul Valéry, Henri Ghéonand others.

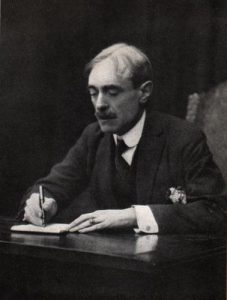

His youth was dominated by the presence of his austere mother

André Gide was born in Paris on 22nd November 1869. His father came from Uzès and was a lawyer ; he held a chair in Roman law in the Law University of Paris. He died in 1880. André, who was an only son, was brought up by his mother. She came from a well-to-do family in Normandy and had a rigid outlook on life. She had been much influenced by her own mother, an almost fanatical Calvinist and had greatly admired her grandfather, Tancrède Gide (described later by André as someone who had been “on intimate terms with God”).

He was not a brilliant pupil at the Ecole Alsacienne, perhaps partly due to the fact that he had to go away frequently for treatment in spa towns to improve his health. His mother took great care of him and he went on to do his lower sixth form at the lycée Henri IV.

From an early age he was friendly with François de Witt-Guizot, whose home Val Richer was situated close to his own home : La Roque in the village of Cuverville in Normandy.

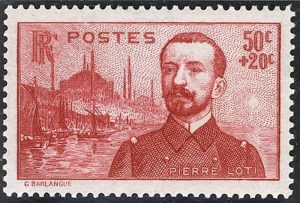

His main schoolfriend was Pierre Louÿs (1870-1925), who later became a symbolist poet.

In 1890, while staying with his uncle Charles Gide, the economist, in Montpellier, he met Paul Valéry (1871-1945) – later described as a “soul mate”.

His mother eventually allowed him to read books from his father’s library and he soon immersed himself in the works of Saint Augustin, Pascal, Bossuet and especially Goethe, whom he held in great esteem.

He was strongly influenced by Amiel’s Journal Intime and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions – these works were introspective in nature and they made such an impression on him that he started to write his own Journal in 1887, which he kept almost daily all his life.

Religious discussion, political involvement

Gide read the Bible a great deal throughout his life and he spent much time meditating about religion, as can be seen by his dialogue with François Mauriac, Paul Claudel, Henri Ghéon, (an agnostic who later openly declared his conversion to christianity). However, due to his puritan upbringing, leading a strictly moral life was considered to be more important than having a strong faith so he did not share the deep religious conviction of his catholic friends.

“There is practically nothing about which I have not changed my mind” wrote Gide in his journal towards the end of his life. This was probably especially true of his political opinions.

He took up the Dreyfus cause in 1898-99, but without much enthusiasm. At the same time, his admiration for Maurice Barrès led him to support the Action Française.

As he was not called up in 1914, he worked in an accommodation centre for refugees, which was a “modest but useful” task. While working there he made the acquaintance of Charles du Bos, who later became a trusted friend with whom he shared his uncertainties and thoughts concerning religious truth.

After the war, Gide took a great interest in colonialism. He spent nearly a year (1926-27) in the Congo and Chad. He described his impressions of this journey and sent these accounts to his friend Léon Blum, who at that time was the editor of a socialist daily newspaper called Le Populaire.

These accounts were later published under the title Voyage au Congo (1927) and le Retour au Tchad (1928).

In the following years he became more and more attracted to communism. For him it was “a new spiritual adventure”. In his Journal in 1936 he wrote “Never have I looked into the future with so much interest and curiosity”.

In January 1934 he went to Berlin with André Malraux to try and obtain the liberation of a Bulgarian communist leader, then in 1936, spurred on by the victory of the Front Populaire, he spent two months in the U.S.S.R., where he met up with Aragon. But he soon realizedwhat was actually happening when he heard about Stalin’s purges and camps. In 1936 he published Retour d’U.R.S.S. and in 1937 Retouches à mon retour d’U.R.S.S., but his friends, who were ardent supporters of communism, reproached him violently for writing such works..

But with age, he distanced himself from the problems of society between the two wars. He lived at the centre of a select literary group (or “cenacle”) of friends and one of the most important members was Maria Van Rysselberghe, known as “La Petite Dame”. He had a brief affair with her daughter, who gave birth in 1923 to a little girl, Catherine Lambert-Gide.

He cut himself off from the world, very involved as an editor of his newspaper, received the Nobel prize in 1947 and died in Paris in 1951.

André Gide was both detested and admired for his work. Although his novels were not very successful when they first came out, due to his scandalous standpoint on some moral issues and lack of popularity for his work today, he must be considered nevertheless as an important writer. Indeed, because of the classical beauty of his language, André Malraux called him “a significant contemporary” of the first forty years of the XXth century.