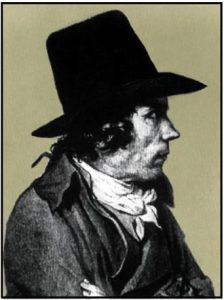

Jeanbon Saint-André (1749-1813), by David © S.H.P.F.

Jeanbon Saint-André (1749-1813), by David © S.H.P.F.

André Jeanbon was born on 25th February 1749, in a manufacturing family who were entrepreneurs, typical of the upper, if not wealthy, middle-class of the textile industry, numerous among Montauban Protestants. In the city, three-quarters of the traders and flour millers were “of the religion” as stated in the “reports” written at the end of the Ancien Régime. As recorded in 1863, the Jeanbon family arrived in Montauban, a town hit by the reformation, in the mid-17th century. They had probably come from Mauvezin, a town now in the Gers department, where there were many Protestants.

As with all Protestants in the 18th century, members of the family were baptised and married in the Catholic church. “Catholic certificates” were then mandatory for civil status. The first protestant certificate was written in 1771 for the marriage of André’s older brother, a proof that things were changing.

The Jeanbon family was definitely Calvinist – but discreet and cautious – although they were present at “Churches of the Desert” meetings and active in maintaining and rebuilding Reformed Churches.

A sailor and a pastor

After studying in his home town from 1759 to 1765, the young André studied seamanship in Bordeaux in 1765-66 and was a naval officer until 1771.

Then, with the support of the “French Committee in Geneva” (“Comité français de Genève”), he went to the seminary in Lausanne founded in 1724 by Antoine Court. He trained for the ministry and was ordained on 21st April 1773. Before leaving Lausanne, Jeanbon, in accordance with the “Churches of the Desert” tradition, assumed the pseudonym of Saint-André, just as Rabaut was called Saint-Etienne.

Even before he was ordained, the clandestine Church in Pau had asked him to come. As soon as 29th April 1773, he was in this textile industry city with a rich Protestant tradition. He soon took on responsibilities. The 1776 “Churches of the Desert” synod sent him to the national synod. At the 1777 synod he was in charge of dealings and disputes with neighbouring synods, a role he also had in 1778 and 1779.

But he was alienated by some of his parishioners because of his law-abiding attitude. They plotted against him and forced him to resign in 1783.

In hiding, he wrote his Thoughts on the civil organisation of Protestant Churches (Considérations sur l’organisation civile des Eglises protestantes) first published in 1848. The implementation of the Edict of Tolerance, signed by the king in 1787 and ratified the following year, was in accordance with his thinking and induced him to resume his ministry in July 1788 at Montauban. Soon after this he started a very successful “religion course” (“cours de religion”), and was also hailed for his oratory skills.

His first steps in politics

After the political turmoil in Montauban in 1790, he fled to Bordeaux where he made friends with many future Girondins. He maintained his political activities and in 1791 his rise began.

He was elected representative of the Lot region (Lot et Garonne was only created by Napoleon in 1808) at the Convention on 6th September 1792, and was awarded a leave of absence by the consistory.

He proved to be an excellent orator and often spoke. Gradually he moved away from the Girondins and was elected president of the Jacobin Society on 2nd November 1792. In January 1793, he voted in favour of the king’s execution. He wrote a very Rousseau-like text, entitled About national education (Sur l’Education nationale) to promote active teaching methods. In March 1793, David and Jeanbon requested the setting up of a revolutionary court of justice. Jeanbon had forgotten neither his home town nor his religious beliefs – he played a key role in buying the Carmes church which was to become the town’s Reformed church.

When he became a member of the Naval Committee, he suggested a reorganisation. On 28th May 1795 he was arrested following the uprising of May-June (Prairial Republican calendar), and was jailed in the Collège des Quatre Nations (presently the Institut) along with David, who later said that the guillotine had stood in the jail yard for two days. He also drew a picture of Jeanbon while they were in prison together. Jeanbon was released six months later.

The Directory, joys and surprises of a new life

He did not go back to the ministry. He was appointed consul in Algiers and then in Smyrna, the most important job in the Levant, where he arrived on 29th October 1798 (8 brumaire an VI). The conquest of Egypt, against the wishes of the Turks, led to his arrest. He wrote about his almost three-year long captivity in Tale of my captivity on the banks of the Black sea (Récit de ma captivité sur les bords de la mer Noire).

Under Bonaparte, and then Napoleon

On 1st December 1801 (10 frimaire an X) Bonaparte signed Jeanbon’s appointment as General Commissioner of the new French departments on the left bank of the Rhine, as well as Prefect in Mont-Tonnerre, but living in Mayenne. He was to stay there until he died.

After the decree of 31st August 1805 (13 fructidor an XIII), which regulated the religious situation in the “reunited territories”, Jeanbon tried to create a faculty of theology at Deux-Ponts in Rhénanie, but failed.

In 1809 he was made Baron of the Empire.

An exemplary and truly Protestant end

Quite separate from what later led to the “Revival” (Réveil) trend, he kept emphasising morals over theology and mysticism, and was little interested in the ceremonies of worship.

He donated his library to the recently created Faculty of Theology in Montauban, which proves how concerned he was about the future of reformation in his city, even though he lived a long way from there.

While taking care of sick soldiers, he caught typhus fever and died in Mayence on 10th December 1813. His funeral oration was delivered in the Protestant church on Christmas Day.

Grateful for his activity as a prefect, the people of Mayenne had a monument erected, which can still be seen today.