Republican Protestants are the enemy of the nation as defined by Maurras

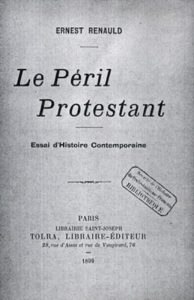

The last decade of the XIXth century was marked by an anti-Protestantism whose intensity has nowadays been forgotten but the most striking example of which was the publication of two books by the nationalist Ernest Renauld : Le Péril Protestant (1896) and La Conquête protestante (1900).

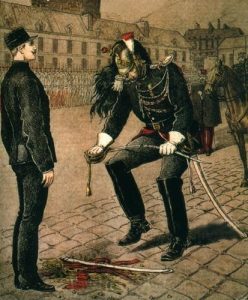

The Dreyfus case, which opposed Catholics and Protestants, was an essential component of anti-Protestantism ; it also explains the term of « Judaeo-Protestantism » which right wing Catholics and nationalists – such as Edouard Drumont, Maurice Barrès and Charles Maurras – used to qualify the Republic. This anti-republican right wing denounced not only alliances between Jewish and Protestant families, but also eventual conversions, such as Alphonse Daudet’s portrayed in his novel L’Évangéliste. The anti-Protestant lobby interpreted common attitudes and thinking of Protestants and Jews – who were often associated in the organization of this new Republic – as being a conspiracy. They denounced the « triple alliance » of Jews, Protestants and Freemasons.

The nationalist Press reminded its readers of the foreign origins of some families, such as the Waddington and the Monod families ; Maurras called them « a cosmopolitan tribe, allied to all the German and Anglo-Saxon races of the world ». Some authors even go further by stating that « religions are races » ; they described the struggle between « Celtic-Latin Catholic races » and « German and Anglo-Saxon Protestant races ».

The Huguenot oligarchy was also denounced as appointing Protestants – often former ministers or liberal theologians – to prominent positions in the senior civil service, while Roman Catholics were said to be excluded. The permanent presence of Protestants in various governments is was a consequence of the diversity in political opinions of influential Protestants. The lobby mostly attacked the prominent role played by Protestants in the field of education (the Protestants and the creation of the republican system of education). For Renauld this new school system was not really secular since it was imbued with the notions of a religious minority.

The « Protestant Party » would betray France. The colonial expansion of a Catholic France, thwarted by a Protestant England, made passions run high. The conflict in Madagascar was an example of this : the Protestants were accused of collaborating with Malagasy nationalism and with British missions from « perfidious Albion ».

Because of its principles of free examination, Protestantism was presented as anti-national and politically subversive. At the roots of the French Revolution, Protestantism could evolve towards anarchy with the added risk of a despotic reaction, such as Calvin’s in Geneva. Protestantism was at the roots of capitalism, which Pope Leo XIII had recently condemned, and likewise of socialism, as it abolishes all hierarchy among men.

With the separation of Church and State and the rehabilitation of Dreyfus, the anti-protestant attacks decrease. « The fates of Protestants and of Jews under the Republic begin to differ : the former complete their integration into the nation, their differences becoming less and less apparent, while the latter become the target of an increasingly aggressive anti-Semitism. In 1940, with the advent of a markedly clerical regime (…), the strong and active sympathy towards the Jewish community becomes apparent once more as a specific feature of French Protestantism are » (C’est alors que la communauté de destin dans la République se relâche entre les protestants et les Juifs : les premiers achèvent de réintégrer la communauté nationale, leur différence commençant à se banaliser, tandis que les seconds sont en but à un antisémitisme qui n’en finit plus de s’aigrir. En 1940, à l’avènement d’un régime aux fortes allures cléricales (…) ce philosémitisme, très particulier aux protestants français, se retrouvera, très agissants, P. Cabanel).