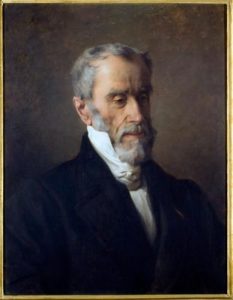

Descendant of a French Huguenot family who emigrated in 1685

Benjamin Constant was the descendant of a Huguenot family of the Artois, converted to Protestantism in the 16th century and settled near Lausanne in Switzerland after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

His father was an Army officer ; his mother Henriette de Chandleu died in childbirth. Due to the mediocrity of his private tutors, his education was somewhat chaotic but his intelligence was revealed at a very early age.

After spending six years serving under the Duke of Brunswick (Commander of the allied armies at the time of the invasion of France in 1792), he came back to Lausanne where he met Madame de Staël in 1794. Their intimate relation, with its ups and downs, lasted more than fifteen years (their break-up lasts five or six years). He followed her to Paris and went into politics after obtaining French nationality thanks to the law of 1790 which granted civil rights to the descendants of families formerly exiled for religious reasons.

His political action was exercised in three periods

- Two years at the Tribunat under the Consulate, where he was to defend a middle-of-the-road policy. Until 1802 he joined the combat of moderate republicans against attempts by both royalists and passionate patriots. Member of the Tribunat for two years, he was excluded by Bonaparte and banished at the same time as Madame de Staël. He settled in Weimar but frequently spent much time in Coppet with Madame de Staël.

- Two months during the Cent Jours : Napoléon entrusts him with drafting the new Constitution.

- Thirteen years under the Restauration : he was one of the leaders of the liberal party and its only theorist. Député during eight years – successively for the Sarthe, Paris, and the Bas-Rhin – he was an outstanding speaker, passionately defending all individual liberties within the framework of the 1814 Charter. He was feared by the “Ultras”, and the “Doctrinaires” block his access his to the Académie, while the liberal wing of his party judged him as too moderate. Public opinion, however, much appreciated him.

He fought his combat by means of the press, and by the publication of political works (Cours de politique constitutionnelle etc.).

All his life he made considerable efforts to reformulate the conquests of 1789 by means of reforms. But he favoured a parliamentary monarchy : a monarchy and conservative peers, associated to a House elected according to the “censitaire” system, with ministers responsible to a legislative power and the separation of judiciary power.

He died on 8 December 1830. His funeral was a popular triumph : students unharness the horses from the hearse to draw it themselves to the Père Lachaise cemetery.

A permanent religious quest

Constant’s religious opinions varied greatly : at times of personal crises, he would feel close to beliefs that he would later abandon. But in his opinion, man needs religion in order to be a man, even though God – in whom one believes or hopes – remains undefined.

His main work in this field is a seven-volume opus published between 1824 and 1833 after twenty years of hard work : De la religion, a glorification of religious feeling.

Religious feeling can only be recognized by the way it manifests itself : a desire for immortality, a need for man to be in harmony with nature, the sense of closeness to a superior being. Constant established a difference between such religious feeling as helps man to communicate with an invisible power, and the religious structures imposed by the Church.

In moments of crisis or despair he would not hesitate praying to God, but his faith was somewhat vaguely defined ; he believed that « religious feeling is quite compatible with doubt, and it is even more compatible with doubt than with such or such religion » (que le sentiment religieux est très compatible avec le doute, qu’il est même plus compatible avec le doute qu’avec telle ou telle religion). Such doubt is of a positive nature and brings progress : doubt breeds renewal and all established creed is an obstacle.

Constant maintained that moral and social commitments are part of religion, along with the highest values, like liberty and human dignity. For him liberty is at the very root of religion which can only develop if all authority is kept well apart. « For forty years I have defended the same principle : freedom in all things, in religion, in philosophy…..in politics ».

A master of psychological analysis

Mention must be made of his best-known novel, Adolphe.