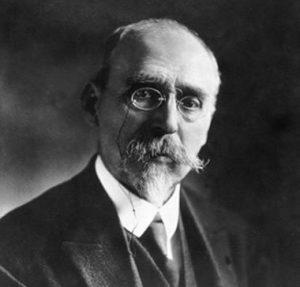

An outstanding academic career

Charles Gide grew up in Uzès in a protestant family – his father was the president of the civil court. His uncle was a widely-recognized jurist and the father of André Gide. Charles Gide studied law in Paris ; in his thesis (1872) : “the right to work in association with others in religious matters”, the main ideas were already in place which were to influence all his later work.

After the “aggregation”, he was appointed Professor of political economics at the Law University of Bordeaux (1874), Montpellier (1880), and Paris in 1898. He also taught in the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées and in the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre. He became a member of the College de France in 1921.

His famous work Principes d’économie politique was a great success – there were twenty six editions in French and nineteen translations into foreign languages (including Braille). In 1918, André Gide wrote to his uncle “How much I have benefited from what you have written ; what admiration I have for the honesty of the theories which you have set forward !”

In 1881, Charles Gide founded the “Revue d’économie politique”.

The leader of the French cooperative movement

From 1886 onwards, he became the theorist of what became known as the “Ecole de Nîmes”, a French cooperative movement whose leading members were protestant (Auguste Fabre, Edouard de Boyve). This political/social organisation was especially present in the South of France. The main idea was a corporation which would enable its members to become emancipated in society ; it was also a structure promulgating democracy and economic efficiency : it did away with the profit system but was not a state system. The idea of cooperation was made accessible to the general public at a congress in Paris in 1885 and in a monthly newspaper L’Emancipation in 1886, which was described by its editor as “a journal of political and social economics.” The idea was put into practice in Nîmes : Charles Gide participated actively in a “Consumers’ Cooperative” ; he studied actual problems of management and the tensions between the cooperatives and private business.

In 1888, the “protestant association for the practical study of social issues” was set up in Nîmes : pastor Fallot was president and Charles Gide was vice-president.

This principle of mutual support was set forward as being a middle road between liberalism and Marxism ; the idea was shared by men like Henri Marion, Emile Durkheim, Léon Bourgeois. It “is not pure idealism, like freedom or equality ; it is a fact which is well corroborated by science and history : the daily continuous interdependence of men on each other.”

One of the founders of Christian socialism

Charles Gide insisted on high moral standards in all his political activities. He underlined the religious aspect of the “New School,” founded on the same concept of solidarity that appears in epistles of the Apostle Paul. When Tommy Fallot created Social Christianity in 1888, Charles Gide was first vice president, then the president of the movement in 1922.

Charles Gide was a supporter of Dreyfus, the French socialist “associationist” ideology and movements advocating social change, but he disapproved of revolutionary socialism. He studied the various social problems of the last years of the XIXth century with a certain degree of moderation, not wanting to cause offence to institutional protestantism, (which showed only lukewarm interest in problems of this kind.) This was despite the fact that the situation was becoming more and more serious with the approach of the economic crisis and the rise of Marxism. The object he had in mind was to find a balance between a religion which refused to acknowledge the existence of a social problem and a socialism which denied man’s spiritual dimension.

After having written articles in which he expressed his open hostility to Bolshevism, Charles Gide was invited to come to the USSR in the autumn of 1923 ; an “integral cooperative organisation” did appear possible, but communism itself was “too red” for him. Recently his work, which was criticised by both the bourgeoisie and the left, has been rediscovered. Apart from the omnipresent idea of solidarity, many of today’s problems were already receiving his attention : the ageing of the population, the difficulty of creating legislation to deal with social problems and in particular the case of pensions. One can also read about the questions he was asking himself concerning the setting up of the state of Israel.