Peaceful times

Protestants in the Midi did not disarm and organised themselves. The siege of La Rochelle, resistance movements in Sancerre, Nîmes and other cities in the Midi, showed that the protestants, who mistrusted their King, could resist as the population sided with them. Getting organised was paramount. The creation of the Union of Protestants in the Midi set up a real parallel government, which could be called a Huguenot State.

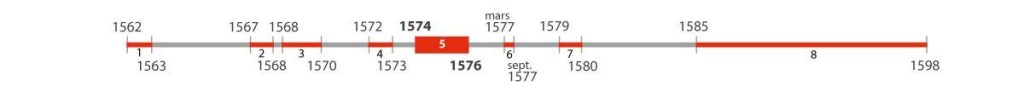

The situation in Paris was chaotic. Upon Charles IX’s death on the 30th of May 1574, Duke Henri de Guise suddenly left Poland, arrived in France in September 1574 and became Henri III. He was crowned King on the 13th of February 1575. He was back in a country where unrest had sprung up again the year before, as the Protestants had taken up arms again as early as February 1574 in the Dauphiné, Vivarais, Poitou and Saintonge regions. These combats marked the beginning of the fifth war of Religion.

Times of War

The royal authority was questioned. Pamphleteers railed especially at the Queen Mother, her intriguing Italian circle was considered as oppressors of the kingdom. Some writings even questioned the legitimacy of the Royal power: the “monarchomaques” differentiated the fallible prince from royal dignity. They stood up for representative institutions, for the people’s authority that, as an assembly, could make laws and choose the King by election. The rebellion was legitimate even if the King did not govern for the good of all. The ideas were largely circulated by Calvinist publicists.

Intrigues developed among princes, rivalries were common place. Most great Lords were armed and surrounded by body-guards. Duke François d’Alençon, the King’s young brother, plotted and requested a bigger participation in power. He was watched by his brother but led a movement comprising Protestants and moderate Catholics. It was called the alliance of the ‘dissatisfied’ requesting a reformation of the State, because tolerating the Reformed worship was first and foremost a problem of political reform. The fifth war lost part of its religious characteristic and became a political war against tyranny.

When unrest appeared again in the Midi, François d’Alençon drew up a plan to leave the Court with princes Henri de Navarre and Henri de Condé and reach Sedan, where Ludovic de Nassau was waiting for them. The plot of Spring 1574 was discovered and the main participants executed. Marshall François de Montmorency was suspected and imprisoned in the Bastille. Count Gabriel de Montmorency, who unintentionally fatally wounded Henri II during a tournament and disembarked in the Cotentin with English troops, was caught and dramatically executed.

The movement of the “Dissatisfied” picked up in the Midi under the impulse of the Governor of Languedoc, Henri Montmorency-Damville, François’s youngest brother, cousin of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, who had fallen out with Catherine de Medici. Though he was a Catholic, a moderate one, he allied with the Huguenots, and offered the French of both religions to lead them to fight the ‘oppressors’ of the kingdom.

Battles were fought in Poitou, Dauphiné and Languedoc. In April 1575 Henri III initially refused to meet the ‘Dissatisfied’s’ requests. But on the 15th of September 1575, François d’Alençon fled from the Court and laid claim to govern with his brother while excluding his circle. The situation became all the more difficult as foreign countries got involved, ie: Henri de Condé made an agreement with Jean Casimir, the son of the Palatine elector, who committed himself to mobilising 16,000 mercenaries. The invasion was stopped by the Duke de Guise at Dormans on the 10th of October 1575. During the battle he was wounded in the face, which won him the nickname ‘scar-face’. A temporary victory because German troops later invaded Burgundy.

Henri de Condé’s army was met up with François d’Alençon’s. The Protestant party was reinforced by Henri de Navarre, who had fled from the Court, after reconnecting with ‘the true religion’. The princes had 30,000 men, more than the royal troops. Duke François d’Alençon, a Catholic leading Protestant troops, hesitated, knowing that Paris was fanatically ‘Guise partisan’. But Prince de Condé ordered him to march to Paris. Negotiations were necessary. Henri III signed the peace treaty called ‘peace of Monsieur’.

The Edict of Beaulieu of the 6th of May 1576 testified of the victory of the ‘Dissatisfied’. It was very beneficial to the Protestants, the most liberal edict since the wars had started. It allowed Reformed worship everywhere in the kingdom, except in Paris and two leagues around, freedom to hold their assemblies, permission to hold any job or position, creation of mixed law-courts and mixed-party chambers in each Parliament.

Every law-suit was dropped, seized goods were handed back. The Protestants were granted their own cemeteries. Notification to attend General Estates was promised. The Protestants though had to pay a tithe to the clergy as did the Catholics. The Catholic religion was reinstated everywhere, even in cities where the Protestant rule had decommissioned the churches.

But above all, the Protestants were granted eight stronghold towns under the responsibility of Prince Henri de Condé, who Henri II had allowed to come back to the kingdom, and was appointed Governor of Picardie. Henri Montmorency-Damville remained Governor of Languedoc, and the king of Navarre, Governor of Guyenne.

The Saint Bartholomew events were denounced. Duke François d’Alençon had his power increased in land and money, and while becoming Duke of Anjou, as had been his brother, he also became an heir to the throne.