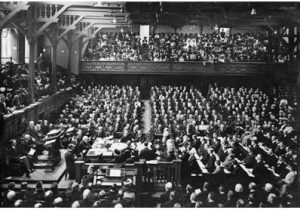

The Synods expressed their views openly on the future of the colonies (1947)

In 1947, some regional reformed synods (Cévennes-Languedoc, Alpes-Rhône) asked the Church to speak out about the Government policy towards the colonies and in the review Foi et Vie (September-October 1947) Michel Phillibert denounced the “long painful silence” of the Church assemblies and protestant press concerning several violent incidents which had taken place in Madagascar, Indochina and North Africa. They said “We refuse to accept nazi methods”.

In 1948, the national synod of Grenoble took up a clear position “against the continuing struggle in the territories of the French Union, for which we hold ourselves responsible”, they “asked the Government to be vigilant about the methods used and to even go so far as adopting a generous policy towards the colonies”.

The issue of Madagascar

A country of particular concern to Protestants where many missions had been sent in the past, was Madagascar. Here, a rebellion broke out in 1947, with violent incidents continuing to take place in the following years. The militias belonging to the French colonists and especially the troops sent out to restore order were unbelievably cruel ; their violent repression resulted in the death of 80 000 people in Madagascar.

In December 1948, a petition was drawn up calling for the Tananarive trial to be brought to an end and reconducted in France. It was signed by the social Christianity movement, together with Catholics in ecumenical groups, militants from the review Esprit, the journal Témoignage Chrétien and the movement called Vie Nouvelle. In 1954, the synod of Le Havre took up a position in favour of granting a free pardon to political prisoners from Madagascar.

The Indochina war (1946 - 1954)

Although there had been hopes of a solution negotiated with the nationalist leader Hô Chi Minh in Tonkien and what amounted to an acceptance of independence had been established (conference of Fontainebleau July – August 1946), France suddenly returned to its former strongly colonial position : on 23rd of November 1946, warships were used to send bombs on Haiphong, causing the death of at least 6 000 victims and an expeditionary force was sent out to re-establish colonial authority. A war then broke out, which lasted eight years. It came to an end when the French army were utterly defeated at Diên Biên Phu (May 1954), and the peace treaty, negotiated by Pierre Mendès-France, was signed in Geneva in July 1954.

In February 1950, a position was taken on the war in Indochina at Issy-les-Moulineaux. In 1952, the synod in Paris asked for negotiations. In 1954, the synod of the Hague expressed “a deep fear that the war in Indochina would drag on interminably” and hoped for peace to be established at the conference in Geneva in July 1954.

The war in Algeria

In North Africa, the violent riots in Sétif in May 1945 and their repression were a sign that things had come to a breaking point between the Algerians and the European colonists, who could not understand that the days of the colonial system of government were numbered. On 1st November 1954, known as “bloody All Saints Day”, war broke out, instigated by the Front de Libération Nationale – it was to last for eight years. In 1957, the army were given the task of maintaining order : their use of torture during interrogation (battle of Alger, January 1957), horrified the French population. On 13th May 1958, supporters of the continuing presence of the French in Algeria held an enormous demonstration. It degenerated into violence. Général de Gaulle came to power on 31st May. In September 1959 he announced the independent rule of the Algerian people and the war came to an end with the treaty of Evian (18th March 1962).

The French Protestants were particularly concerned by this war ; between 1954 and 1963 their position was expressed 24 times in the protestant press. In June 1954, five months before the war started, the national synod called on the protestants of North Africa to take action so that “everyone should be able to lead a normal life” and that all feelings of hatred should cease. Throughout the war the protestants continually denounced the methods used by the police to “establish peace”, also the torture and summary executions. In 1957 the Cimade began to work in Alger, Médéa, and the regrouping centres. The council of the Fédération Protestante de France made an official protestation to the authorities on 12th March 1957 and again on 23rd March 1958, beseeching “the Government once more to bring to an end the violent repression which was causing incalculable harm to the image of France as a nation in the eyes of the world”. André Philip, Paul Ricoeur and Daniel Parker joined forces with the Catholics H.Marrou, J.M.Domenach and A.Mandouze to create a committee of “spiritual resistance”.

In May 1959, pastor Boegner and cardinal Feltin, the archbishop of Paris, appealed to the Government to take action over the people (there were a million of them), held in regroupment centres. A decision was taken at the national synod of Toulouse in June 1960 to distribute 8000 copies of a white book called “A study by the Church of the Algerian problem” throughout the parishes, in order to make protestants aware of the situation and to stimulate a reaction on their part.

In November 1960, the Assembly of Montbéliaird made a firm declaration that “this war is causing the inexorable deterioration of the moral and legal status of the State”. It resulted in a strong reaction on behalf of the government. One of the reasons for this was that it brought up the thorny question of insubordination (many protestants had been present among the 3000 rebels of 1960), the refusal to accept torture and the freedom of conscience. In December 1957, Etienne Mathiot, the pastor in Belfort, (who had formerly been pursued by the Gestapo), was arrested because he had helped one of the FLN leaders to escape into Switzerland. Pastor Boegner accused the Ministry of Justice of acting in a deplorably corrupt manner. At the trial in March 1958, several pastors (Georges Casalis, Maurice Sweeting and Charles Westphal, vice president of the Fédération Protestante de France) were summoned before the court to witness for the defence of Mathiot ; in spite of this, he was given a prison sentenced of eight years.

The leaders of French Protestantism were not all in agreement however, over the question of bringing about peace. Pastor Bourguet, who was president of the national council of the Reformed Church, realized that there were some members of the protestant reformed Church within the European Algerian community who were averse to any form of negotiation. Some councils were so concerned about the possibility of a split arising in the Church, which would be of inestimable harm, refused to take up any position against the Government. 1961 – 1962 were difficult years for the Church : the Algerian protestants asked the Church assemblies to stop repeatedly publishing texts about Algeria and the colonists who wanted Algeria to remain French at all costs started up a newspaper called Tant qu’il fait jour.

The role of the press

The press played an important role and in particular concerning Algeria.

The weekly review Réforme, which represented the majority of French Protestants, was on the whole very cautious in its attitude to “the colonial issue”. In 1954, France was “still considered as being beneficial to the Algerians” and the first acts of terrorism remained incomprehensible. However, religious convictions led to a gradual change of heart and in 1959 Algeria became “a kind of obsession”. The Easter edition was all about Algeria and the war there was considered to be “a human tragedy”. It expressed concern at the manifest confusion of the Europeans in Algeria, was “dumbfounded by the horrific acts of terrorism ” carried out by the FLN, but was equally opposed to the torture “which was becoming commonplace” according to Albert Finet, the editor of Réforme. The regroupment centres were described as “concentration camps”. Some leader writers, Marcel Niedergang and Jacques Ellul, defended the situation of the persecuted muslims.

Other protestant newspapers were more outspoken in their opinions, some even bordering on the extreme. Many special articles and pieces of information about Algeria were published in Le Semeur, Foi et Vie, Cité Nouvelle, (which was the mouthpiece of the Social Christian Movement), and Cahiers de la Reconciliation. From 1955 onwards, all these newspapers considered the necessity of negotiating with the rebel leaders and bringing the war (which had been brought about through the colonies), to an end.

Totally opposed to these attitudes was the journal Tant qu’il fait jour, which was first published under the inspiration of pastor Pierre Courthial, (who, after the second edition, decided to stop writing for it in order not to reveal a political standpoint which might shock his parishioners). The Editor expressed opinions of the extreme right, in defence of the French in Algeria, making a stand against Réforme, which was considered to be too left wing. The paper’s attitude was to protect the Europeans and all Algerians against the FLN, continue the evangelization of the Muslims and prevent Algeria from “falling into the grip of the communists”. The positions of Christianisme and even Réforme were violently attacked – the latter was even considered to be “out of their minds”. To abandon the Europeans of Algeria was seen in the same terms as the protestants who were persecuted at the Révocation de l’Edit de Nantes. Tant qu’il fait jour upheld the putsch led by the French generals, the setting-up of the OAS and described the Evian treaty as “a new Saint Barthélemy”. Tant qu’il fait jour’s last edition was published in June 1962. The protestant Jacques Soustelle was a typical example : he had been a former fellow-soldier of Général de Gaulle, chose to support French Algeria and wrote to Brissaud in order to protest against the “gangrene of the protestant journalists”. In his book l’Espérance trahie, he compared those defending French Algeria to the Protestants who had been persecuted by the armies of Louis XIV.