Peaceful times

For four years after the Peace of Amboise imposed by Catherine de Medici, the state of things was still precarious with trials against protestants who plundered churches, with attacks and killings of a smaller number of Protestants by organised gangs. Each side hired mercenaries to ensure its security. Religious fanatics fought against attempts to make rebel parliaments record the edict and its measures. Some governors, especially in the Midi region, did not follow royal directives, imposed taxes and fought against judicial decisions. The unity of the kingdom was threatened.

In January 1564 Catherine de Medici, knowing how much the French loved their king, decided that the Court with the young Charles IX and his brother Henri d’Orléans, the eleven-year-old Henri de Navarre, as well as constable Anne de Montmorency and Cardinal Charles de Lorraine should go on a tour of France, to show the king and exhibit the prestige of the monarchy.

Upon Philippe II’s request, who sent his wife Elisabeth – the daughter of Catherine de Medici –, the queen had a political meeting with the Duc d’Albe in Bayonne between 15 June and 2 July 1565. The latter asked for all pastors to be expelled from France, for the decisions of the Council of Trente to be accepted, and for repression to be strengthened. The negotiation failed, and Catherine de Medici made only vague promises.

The tour lasted almost two and a half years, from January 1564 to May 1566, when the king came back to Paris. Meanwhile Catherine de Medici noted the apparent quietness and loyalty of the people, even of the Huguenots, while Catholicism dominated there was an apparent peace.

She believed that the pacification of the kingdom was established. But in August 1566 Philippe II sent an army from the Milan region to the Spanish Flanders to subdue the Protestant uprising. This large army went through the Savoie and Franche-Comté regions, bordering the frontiers of France.

The Protestants were worried that the results of the Bayonne meeting remained secret. The Protestant leaders, such as François d’Andelot, no longer commanded the respect of their Catholique soldiers. The prince Louis de Cordet was publicly insulted by the young (just 16 years old) Duke of Anjou, claiming command of his troops as Lieutenant Général.

In June 1567 Pope Pie V condemned the Huguenots. Their leaders Louis de Condé, Gaspard de Coligny and François d’Andelot left the Court. They were determined to take up arms again as early as Autumn 1567. They were worried by the growing influence of cardinal Charles of Lorraine on the young king Charles IX, and contemplated forcefully shielding the king from that ascendency.

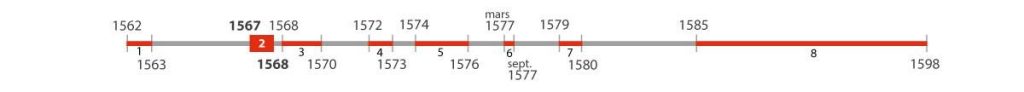

This is known as the surprise of Meaux. But the king was warned, thwarted the attempt and came back to Paris under the watch of his Swiss guards. 26 September 1567 was considered the start of the second war of religion. The royal power was challenged and Anne de Montmorency was entrusted with conducting the hostilities.

War times

Cities in the Dauphiné and Midi regions under Louis de Condé rose up. Outbreaks of violence took place on both sides. On 30 September 1567 during the Michelade, 80 public figures, priests and clergymen were thrown in the well in the court of the bishop’s palace. Montauban became protestant again, as well as Orléans.

Louis de Condé’s army stationed in saint-Denis besieged Paris. In Paris the Catholics violently went after the Huguenots. The royal army under constable Anne de Montmorency decided to get out of Paris. His army was 20,000 strong, whilst the Huguenots had 5,000.

On 10 November 1567, the battle of Saint-Denis lasted 2 hours, and was indecisive. During the battle constable Anne de Montmorency was wounded and refused to surrender, but was shot in the back. He was pulled out by his sons but died 2 days later. Sumptuous funerals were organised in his memory. Assistance was sent to both sides. The Calvinist Elector Palatine Frederick III sent 10,000 knights to France through Lorraine. Gaspard de Coligny joined that army at the beginning of the year 1568. From the Midi region 4,000 men joined the troops of Louis de Condé and beseiged Chartres. Italian and Swiss troops came and reinforced the army of the king, but the 30,000 Protestants remained a threat. Paris was under siege again, and both parties were exhausted. The harsh winter and the lack of resources made negotiations necessary.

After long negotiations a peace was signed on 23 March 1568: the edict of Longjumeau restored the edict of Amboise. But safe strongholds required by the Protestants were refused, except for La Rochelle. Though it seemed more favourable to the Protestants, the edict meant only a truce. Nothing had been gained by the war.

Confronted by the failure of her moderation policies, Catherine de Medici dismissed chancelor Michel de l’Hospital in May 1568, who deemed the monarchy more important than religious unity. The regent took the side of the Catholic cause.