Biographical landmarks

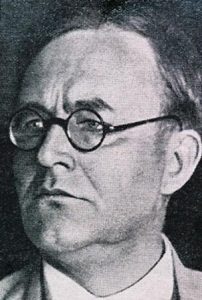

Dietrich Bonhœffer was born in the then German Breslau, today the Polish Wrocklav, the seventh child of an upper-class Prussian family. He was one of the great theologians of the 20th century, and probably the most attractive. He was executed by the Nazis, hanged at the Flossenburg concentration camp, a few days before the war ended, after having been imprisoned in Berlin for more than two years. Thus he was remembered as much for the testimony of his exemplary and brave Christian life, as for the depth of his theological thoughts. Bonhœffer’s Christian militancy, political action and theological reflection were inextricably intertwined. One cannot talk about his theological thoughts without mentioning what he experienced within the University and the Lutheran Church, outside them and finally against them.

The life and thoughts of the Berliner and theologian can be divided into three separate periods.

The university years from 1927 to 1933

Bonhœffer was a theologian of the Church, and open to the world. He reflected on the reality of the Church with a very Lutheran approach and focused his thoughts on the weakness of Christ on the cross. At an early age he wrote bright university theses about the Church as the mystical body of Christ, which made him known in the university where he began to teach. Alongside his teaching he entered the international protestant ecumenical movement, where he established precious relations with foreign Churches. He studied in the USA and was a trainee-pastor in Barcelona. Though he was born in a very privileged and educated family, he committed himself to helping children in a poor area of Berlin.

The confessing years from 1933 to 1942

After a stay in London as the pastor of the German community, Bonhœffer went back to Germany. He turned out to be a militant theologian and struggled for the protestant church to resist nazification. He publicly denounced the idolatry of the Nazi regime on the very day when Hitler took office, in January 1933. He was one of the founders and managers of the confessing Church, opposed to the mainstream tendency to either ally to Nazism, or adopt a neutral attitude. He was one of the few theologians of his times to oppose the marginalisation, and then the persecution of the Jews. From 1933 to 1937 he led a clandestine seminar at Finkelwalde in Pomerania with a view to educating the future pastors of the confessing church. There he wrote two fundamental books The price of Grace (Nachfolge) about the cost of Grace and the need to follow Christ even in suffering, and About community living describing the almost convent-like way of living at the confessing seminar. As the regime became more and more threatening, he decided to leave for the USA, where he was offered a professorship by some friends in 1932. But he could not bear living far away and went back to his homeland on the eve of the war. He pursued a very intensive and often underground activity within the confessing church. He simultaneously initiated links with the resistance network thanks to the complicity with high ranked relatives in the German administration.

The political years from 1943 to 1945

He lived his faith in solitude, abandoning the Church and man.

Bonhœffer realised that caring for the Church was not enough, but that caring for the world was also a requirement, and that the destructive madness of the Führer should be stopped. He was arrested and imprisoned in April 1943, a few weeks after getting engaged. In prison he wrote some of his most beautiful texts in his probably best known book Resistance and Submission. He predicted the emergence of a world in which “God as a hypothesis” would no longer exist, and founded a new way of thinking about God and talking about him. Some heralded him as an apostle of secularism. But they forgot his intense spiritual life in prison, which thrived on praying and regularly reading the Scriptures. He never gave up his hope for a new world in the future, a world of peace, reconciled with itself and God.

The influence of Bonhœffer on contemporary theology

It was overwhelming. He was well-known, studied and translated on all five continents. The Catholic Church acknowledged the outstanding believer, and considered him a courageous witness of the confrontation between faith and modern totalitarian ideologies. In France Bonhœffer was discovered in the late 1960s, notably thanks to André Dumas’s work. In those days the trend was to consider his political rather than his religious stature. After a sort of eclipse, Bonhœffer’s personality and thinking revived interest when the confessing faith and the dialogue with the word were re-discovered.