A complex geography

The geography of the installation of Protestantism in Alsace can explain the scattering of remembrance places. Indeed, the entanglement of territories that remained Catholic with those that became Protestant caused a great complexity of the denominational map, which was largely defined by the 16th century, in spite of many political turmoils.

Catholic territories were a majority

In the 16th century, the House of Habsburg possessed two-thirds of the Haut-Rhin region and the Hagueneau region in the north. The properties of the Duke of Lorraine extended to Alsace.

Moreover, ecclesiastical territories covered a great part of Alsace. The bishopric of Strasbourg was the most important with a territory ranging to the South to Sélestat, to the West and to the North to Saverne, amounting to half of the Bas-Rhin and part of Haut-Rhin. Because of its wealth, many princely families of the Empire tried to retain it within the family, especially the House of Bavaria, and then the Honstein family at the time of the Reformation. Other territories were ecclesiastical propert, such as the bishopric of Spire to the North, and that of Basel in the South.

On the eve of the Thirty-Years War, the House of Habsburg still ruled over most of Alsace.

Territories that became Protestant

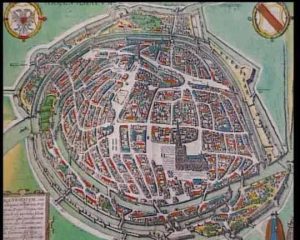

- Strasbourg

The city of Strasbourg, already emancipated from episcopal rule in the 13th century, was a free city under no authority except that of the Holy Empire, to the diets of which he sent his representatives. As early as 1517, printers in Strasbourg handed out Luther’s writings, which spread quickly thanks to strong characters such as Zell, Bucer, Capiton, and the crucial support of the population. Around the year 1525, Strasbourg was committed to Lutheranism. In 1538, it welcomed Calvin who drew on the new worship practices in Strasbourg Church, especially the use of psalms, as well as initiating worship in French for the Huguenot refugee population.

In 1566 the city bought the Lordship of Barr and expanded its territory, and the authorities hoped that the bishopric of Strasbourg could open up to the Reformation, but to no avail because the relations between Protestants and Catholics remained stressed after a time of relative peace.

Several small or average territories were stimulated by the Strasbourg example, and most of them turned to Protestantism.

- Lower-Alsace

The Hanau-Lichtenberg county comprised about one hundred municipalities all over Lower Alsace, this region greatly suffered during the Thirty-Years war (1618-1648).

Palatine areas – some dependancies of various branches of the Palatine House swung between Lutheranism and Protestantism as their sovereigns chose, like Bischwiller. Cleebourg and Oberseebach had Calvinist leanings as did the Lordship of La Roche. The most important ownership of the Palatine House in Alsace was the county of the Petite Pierre.

A lot of small territories, sometimes 2 to 3 villages, theoretically dependent on the Empire, turned to the Reformation, often on the initiative of their inhabitants, the county of Sarrewerden and the ‘seven Protestant villages’, for instance.

Territories dependent on free cities: Haguenau, Obernai, Sélestat.

- Higher Alsace, ruled by the Habsburg

The House of Wurtemberg had property in the Haut-Rhin area, especially the Lordship of Riquewihr and the county of Horbourg.

Territories dependent on free cities: Munster, Colmar.

Mulhouse: at the end of the 13th century, the city had already obtained the rights of a free city in the Empire and was emancipated from the tutelage of the Basel and Strasbourg bishops. Surrounded by the lands of the House of the Habsburg, Mulhouse had asked the Swiss for support, and in 1515 the city was allied to the Swiss Confederation. The Reformation was introduced following the Basel example, and Mulhouse was Reformed in 1529 until it was joined to France in 1798.

The evolution of the Alsatian Protestant community

The crucial steps were as follows:

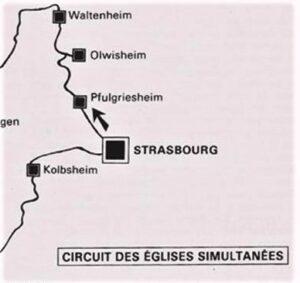

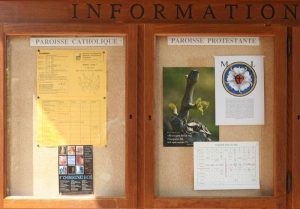

The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, then the surrender of Strasbourg in 1681 turned Alsace into a French region, but Alsatian Protestants kept their religious rights. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 – the Edict did not cover Alsatian areas, as they then did not belong to the Kingdom of France – entailed a coercive policy, which did not reach the same intensity as in other French regions. Many churches were used by both Catholics and Protestants: that ‘simultaneum’ was a specificity of Alsatian memorial sites.

From the early 19th century until the German annexation in 1871, Churches in Alsace were ruled by the Concordat and the Organic Articles signed by Bonaparte. Before WWII, a specific local right ruled over Alsace and Moselle. It stemmed from French laws before 1870, not repealed by the German administration, and from German laws promulgated by the German Empire between 1871 and 1918, but also from legal provisions of the time adopted by local administrations, and finally from French laws passed after 1918, and maintained by the law of 1 June 1924. Besides the very important fact that the Church and State separation law was not applied in the three departments, the law of 1 June 1924, clarified the fact of four acknowledged types of worship – Catholic bishoprics of Strasbourg and Metz, Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine, Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine, Jewish Consistories of Strasbourg, Colmar and Metz – were private and autonomous institutions pursuing general interest activities. They were organised within the framework of public law and funded by the State and the municipalities.

Public primary schools were neutral, as well as denominational secondary schools, religious education is part of the official school programme for on:e hour a week.

Today, the Alsatian Protestant community comprises 23,000 Lutherans, mainly in the Bas-Rhin region, linked to the Church of the Confession of Augsburg in Alsace-Lorraine (E.C.A.A.L.), and 50,000 Reformed, mainly in the Haut-Rhin region, belonging to the Reformed Church of Alsace-Lorraine (E.R.A.L.). The two Churches are now coming closer within the Protestant Church in Alsace-Lorraine.