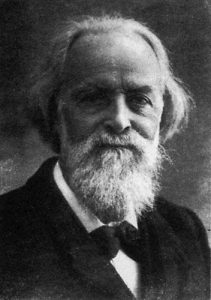

Elisée Reclus defended many noble causes

Elisée was born in Sainte-Foy-la –Grande (Gironde). He had thirteen brothers and sisters; his father was a Calvinist pastor; later he became a teacher in the Protestant College in Sainte Foy.

He first went to school in the Sainte Foy college, then at the age of 12 as his brother Elie, he went to a college run by the Moravian Brothers (Lutherans) situated on the banks of the Rhine, which took in pupils from all over the world. He later returned to France and started studying theology at the Montauban Theology University; however, he was sent away after a few months because he did not respect the rules and was a keen Republican. In 1851 he went to Berlin to study socio-economic geography at the university situated in the capital.

He met up again with his brother in Strasbourg and decided to go back home; he had already published his first Anarchist pamphlet.

When Napoleon III carried out his coup d’état in 1851, Elisée and his brother held Republican ideas. The day before they were due to be arrested they escaped to England, where they lived in great poverty. In fact, Elisée went as far as the United States to take up a job as a tutor to a plantation owner’s family of French origin near New Orleans. While living there he discovered the world of slavery.

When he returned to Paris he joined the Geographical Society, where he met Blanqui and Proudhon. He wrote many articles for “La Revue des deux Mondes” (which dealt with socio-economic geography, international politics and literature), had “La Terre” published, contacted the Russian anarchist Bakounine and became an official member of the Anarchist Movement. He participated in many international meetings with themes such as liberty and peace. In 1864 he set up a bank with his brother Elie called the Crédit du Travail.

In 1870 he joined the army during the siege of Paris and in 1871, during the Commune, he became a member of the National Guard; he was arrested and sentenced to deportation but international scholars and in particular those from Britain, took up his cause: the French Government was impressed by this long list of signatures and reduced his sentenced to ten years exile.

He then settled in Lugano in Switzerland with his wife and two daughters – his brother Elie also lived there. This is where he began to write his great work “A New Universal Geography”, which ran to 19 volumes. In 1877, writing in the review “Le Travailleur” he robustly defended stated libertarian communist ideas.

In 1880, he took advantage of the amnesty which was granted to offenders who had been sentenced during the Commune. He was able to return to Paris and began to travel worldwide. The first volumes of his great work “La Nouvelle Geographie Universelle” began to be published, with the last volume, number 19, coming out in 1894. Elisée gradually acquired an international reputation as his work was translated into many languages; he received many honorary distinctions and in particular the gold medal award of the Paris Geographical Society.

In 1892, he was offered a Professorship at the Free University of Brussels; however, due to many violent Anarchist events taking place in Europe at this time the offer was later withdrawn. The Université Nouvelle was then set up and Reclus’ first lectures attracted many students. Towards the end of his life he had many works published which dealt with socio-economic geography and philosophical history. His book “L’Homme et la Terre”, which he took many years to complete, was published shortly before he died of a stroke on the 4th July 1905. He was buried in Brussels.

The themes of freedom of conscience and fraternity, applied to both the scientific and political spheres, can be found throughout Elisée Reclus’ work. He believed in the fraternity of individuals and of all races living on earth.

In 1897, he wrote in “L’Evolution, la Révolution et l’Idéal Anarchique”: ‘Our destiny is to achieve a state of ideal perfection where nations need no longer be submitted to any form of government: this is Anarchy, the highest expression of order’. Although he rejected Christianity, morality is the basis of his political and social viewpoint.

His combination of scholarly geography and political anarchy embarrassed the university world, which is why he has been partially forgotten.