How the Protestant Church was organized

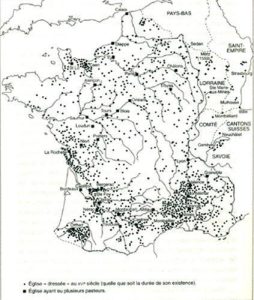

Reformed churches in the 16th century © Musée du Désert

Reformed churches in the 16th century © Musée du Désert

John Calvin decided to organize the structure of the French Protestant Church – this began in Meaux: from 1555 onwards, other churches were ‘established’ in Paris, and especially in the Languedoc, Provence and the Garonne valley. There was a secret meeting of Church leaders in Paris in 1559. At this first national synod, members voted a confession of faith and an article of Church discipline, both inspired by John Calvin. From 1555 onwards, more and more people joined the Reform Movement; they were mostly to be found amongst the nobility, the population living in towns, in the Southern provinces, Normandy, Brie and Champagne.

When Henry II died in 1559, some aristocrats belonging to the King’s Council joined the Reform. Protestantism was no longer a secret movement and began to enter the world of politics.

Events leading up to the Religious Wars

In King Henry’s court there were powerful, ambitious Catholic noblemen, including Duke Francis of Guise, a notable military leader much admired by the Parisians and his brother, the Cardinal Charles of Lorraine. They became increasingly concerned when the king died accidentally on the 10th July 1559 as he had always been considered as a bastion against the ‘Lutheran invasion’. Although Francis II was king of France, he was in fact little more than a puppet in the hands of the Guise brothers who gradually became very powerful at court.

In 1560 some Protestant noblemen planned the removal of the young king from court, away from the dangerous influence of the Guise brothers: this was known as the ‘Amboise conspiracy’ but it was never carried out. The Guise brothers took revenge by ordering a great many executions, while the Protestants rebelled, seizing hold of many Catholic churches. Violence increased on both sides. When Francis II died in 1560, Catherine de Medici, Henry II’s widow, became regent as the new king, Charles IX, was only 10 years old. Catherine saw the power of the Guise brothers as a dangerous threat to peace and with the help of the new chancellor Michael de l’Hopital she tried to gain the confidence of the Protestants and put an end to hostilities between the two religious parties. As the monarchy became increasingly weak, so the nobility became increasingly powerful, the crisis soon became not only religious but also political. In 1561, Catherine de Medici organized a gathering of both Catholic and Protestant theologians at the Colloquy of Passy with a view to reconciliation, but they did not manage to agree on the question of Communion.

Even though the Colloquy never achieved its aim, Catherine de Medici issued an edict in January 1562 which officially recognized religious diversity. Protestants were allowed to hold consistories, synods and to celebrate a public act of worship: this was no longer held at night as before but it did have to be held outside the jurisdiction of the towns and in the presence of royal officers; pastors were now officially recognized if they swore an oath of allegiance to the royal authorities. On the other hand, the Protestants had to give back the Catholic churches and ecclesiastical objects which had been seized: they were not allowed to disturb mass, Catholic ceremonies or desecrate religious symbols. The position of the Protestants was greatly strengthened by this edict.

As for the Catholic population, especially in the North of France, there was a negative reaction to this turn of events ; poor people mistrusted this ‘rich people’s religion’ and all the more so because the Protestants were becoming increasingly violent and aggressive: in march 1562, they massacred Catholics in Brignoles , destroyed sacred objects, profaned the Holy Bread and attacked priests. On the Catholic side, similar actions took place, especially in Northern France. The massacre of Huguenots in Carcassone and Toulouse was as cruel as ‘the first Barthélemy’, another terrible massacre, according to the historian Michelet. The situation was becoming explosive. Sadly, the edict of 1562 came too late and the regent was unable to enforce it. The Wars of Religion began in earnest after the massacre of Wassy.

In Wassy, in the Champagne region, an act of public worship was being held by the Protestants on the 1st March 1562 in a barn which was probably within the town ramparts, thus openly breaking the law which had been enforced in January. Duke Francis of Guise, with an escort of soldiers, happened to be passing through the town, which was on his own land. At first there were violent disputes and later acts of violence. Francis and his escort attacked the barn, killing 50 Protestants, among whom there were women and children, leaving 150 wounded. Protestants considered the incident as an act of provocation and for them the Wars of Religion had their origin in this massacre. The Catholics, on the other hand, considered the attack on Orléans by Prince Louis of Condé as the real starting point of hostilities.