A military life at the service of the crown

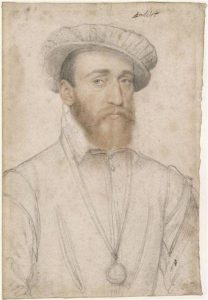

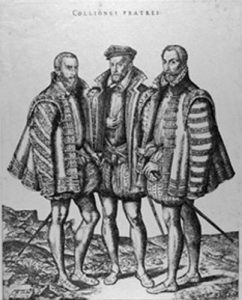

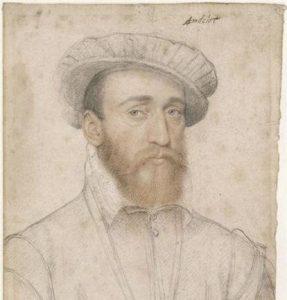

Gaspard II de Châtillon, Lord, then Count de Coligny was the third son of Gaspard I de Coligny, Marshall of France, and of Marie Louise de Montmorency, the sister of Constable Anne de Montmorency. Pierre, his elder brother Lord of Châtillon died in 1528 ; his second brother, Odet de Châtillon, Cardinal in 1533, Archbishop of Toulouse, converted to Protestantism, and married and left several children when he died in England ; his younger brother, François, Lord of Andelot was his comrade in the struggle for the Protestant cause.

In 1522, when his father died, the constable took the Coligny children under his wing. As Louise de Montmorency was appointed lady in waiting to the queen, the Châtillon brothers befriended the Guise. Coligny’s whole life was marked by his relationship with the Guise.

Gaspard had a humanist education at the Court. He had a studious youth and intended to have a military career with his brother François d’Andelot, while his other brother Odet de Châtillon received his Cardinal hat at 16 years of age.

As early as 1542 Coligny entered into arms and relentlessly fought for Francis I, and then for Henri II, against the Spaniards and their allies, and also against the English. He proved very brave and was wounded several times. He took part in winning Boulogne back from the English and negotiated with them the return of the city, thus proving to be a great diplomat.

In 1547, Coligny married Charlotte de Laval (1529-1568) and they had eight children.

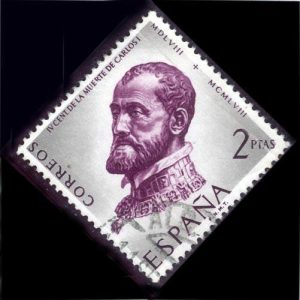

The Italian wars opposed France to the Habsburg from 1494 to 1559, the battle fields were in Italy but also in Northern France and in the United Provinces – The Valois and the Habsburg fought over the leadership of Europe.

In 1552, Henri II seized three bishoprics, namely Metz, Toul and Verdun. Charles V’s troops besieged Metz. Coligny commanded over 10,000 men on foot and won the victory at Renty against the Spaniards. Charles V lifted the siege ; François de Guise, in charge of the defence of Merz received all the glory, but Coligny was rewarded for his actions with the office and title of Admiral of France. The king also appointed him governor of Picardy.

The conflict against the Habsburg went on, the Vaucelles truce was broken by the King of France, so that Coligny kept fighting. He was ordered to defend the city of Saint-Quentin. He locked himself in the city but had to capitulate a few months later, in 1557. He and his brother d’Andelot were made prisoners. The military campaign was a disaster despite the Duke of Guise winning back Calais. The combatants were tired and the war ended with the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, signed in 1559 with the king of Spain, the French claims on Italy were put to an end and France was also made to return the places it occupied in Flanders.

Coligny regained his freedom after the signing of the peace treaty and in exchange for the payment of a ransom. He then took refuge in his castle of Châtillon-sur-Loing.

Coligny admiral of France

At the end of 1554, Henri II asked Coligny to prepare an expedition to Brazil to create the colony of Antarctic France. The expedition, entrusted by Coligny to the vice-admiral de Villegagnon (1510-1571), was launched in 1555. The settlement was founded on an island in the bay of Rio de Janeiro. Villegagnon built a citadel there which he named Fort-Coligny. Protestants were encouraged to join the colony. But the settlement was short-lived, as the colonists were expelled in 1559 by the Portuguese.

After the death of Henry II in 1559, Coligny kept his position as admiral: he organized a relief fleet for Scotland. This mission led him to resign as governor in 1560.

In 1562, Coligny launched a force led by two Protestants, Jean Ribault and René de Laudonnière, to establish a settlement in Florida. Under the blows of the Spaniards, this colonization effort did not succeed.

Conversion to the Reformed faith

Gaspard de Coligny’s personality predisposed him to Calvinism. Serious and very pious, he exercised a very austere discipline on himself. He was sensitive to the preaching of Calvin and felt the spiritual deficiencies of Catholicism.

He was imprisoned in Charles V’s prison from 1557 to 1559 with the Bible as the unique book to read, and the despair of solitude and illness led him to a mystical crisis. His d’Andelot brother’s exhortations and his correspondence with Calvin convinced him to convert to Protestantism. He only took a public stand for Protestantism later.

The leader of the Protestants

In 1559, upon Henri II’s death, the Guise clan seized power and imposed more radical measures against Protestantism. There were numerous martyrs, Anne de Bourg’s fate particularly impressed and shocked Coligny. The bloody repression after the Conspiracy of Amboise in 1560 prompted Coligny to display his commitment to the Reformation. In July 1560, he submitted the demands of the Protestants to Catherine de Medici and king Francis I, particularly the opening of worship places. He expressed his growing hostility towards the initiatives of the Guise, as well as his opposition to their religious policy and to their government.

Coligny was soon known as one of the leaders of the Reformed party. He played an important role at the Colloquium of Poissy in 1562 where he had Théodore de Bèze invited. Unfortunately Catherine de Medici’s bold idea to reconcile Catholics and Protestants and to have both religions coexist within the kingdom was ambandoned.

As the attempt to coexist had failed, the wars of religion began.

The wars of religions

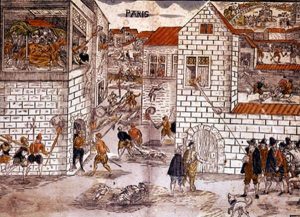

In 1562 the Protestants feared a severe repression by the extremist Catholics influenced by the Guise. The massacre in Wassy was the first excess, which was all the more serious as it was the work of François de Guise. The Protestants no longer felt secure after the first war of religion in 1562 and 1563.

Louis de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, was the soul and leader of the Protestant army. Coligny, an eminent legalist, took up arms against the King’s troops after deeply reflecting on his duties as a subject, and on his religious convictions. He was at the head of the Protestant cavalry. To finance the troops he commanded, he signed the Treaty of Hampton Court with Elizabeth I, which gave her part of Le Havre harbour and guaranteed the return of Calais, in exchange for financial assistance.

After a number of battles, the death of Antoine de Bourbon and the murder of the Duc de Guise, the first war of religion ended with the Edict of Amboise, in 1563, to no one’s satisfaction.

In 1567, the second war of religion broke out. Coligny took part in it, commanding the fore-posts of the army of Condé. Anne de Montmorency, a former protector of the Châtillon brothers was killed in Saint Denis during the siege of Paris. In 1568, the Treaty of Longjumeau mentioned that the Protestants would lose all their strongholds except for La Rochelle.

Disarming the Protestants seemed a manoeuvre of Catherine de Medici as the Edict of Longjumeau was revoked, and the hunt for Protestants was launched that very same year. There was killing and looting everywhere. It was a dark period for the Admiral who lost his wife Charlotte de Laval (1530-1568) in an outbreak of typhoid that affected Orléans where she had taken refuge, and then he had to leave Châtillon. The main Protestant leaders fled to La Rochelle except for the Cardinal, his brother, who went to England to find the necessary funds to keep fighting.

The third war of religion (1568-1570) saw a Protestant defeat in Jarnac in March 1569, where Louis de Condé was killed. The Protestant troops, now under Coligny, won at Roche-d’Abeille, but lost at Moncontour. The war went on with much local fighting that resulted in horrible massacres and looting. Coligny justified them by the need for retaliation for the King’s troops abuses. The Protestant armies managed to reach as far as the Charité-sur-Loire and to threaten Paris from there. The King eventually suggested a peace be signed in Saint-Germain in August 1570. It was a victory for the Protestant side and particularly for Coligny.

The admiral’s death

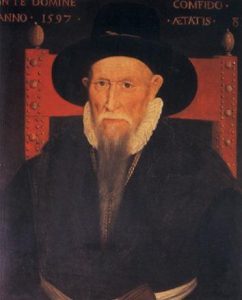

From then on Coligny’s life was more peaceful. He remarried in 1571 to Jacqueline de Montbel d’Entremont, the widow of Count du Bouchage and returned to the king’s good graces.

He continued supporting the Protestant cause. He notably stood up for the Netherlands subjected to Spanish Catholics repression, and advocated a French intervention against the Habsburg. Its objective was to bring Catholics and Protestants together against a common enemy. Catherine de Medici saw it as an attempt to reinforce Protestantism and was violently opposed to it. Coligny recruiting troops to fight in the Netherlands was seen as an act of disobedience. It resulted in the king Charles IX’s Council wishing to eliminate Coligny.

On 22 August 1572 at the end of a game of tennis, the king had him dragged inside, Coligny was shot at and wounded by Sir de Maurevert. He was brought home to the rue de Béthisy – now rue de Rivoli – where the king sympathetically visited him. He placed his confidence in the king’s word against his friends who urged him to leave Paris. He also did not wish to offend the king and refused to risk starting a new civil war.

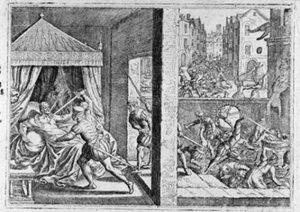

In the evening of 23 August, the king’s Council launched the massacre of Protestant leaders. They were assembled in Paris for the marriage of Marguerite de Valois with Henri de Navarre, and they were murdered.

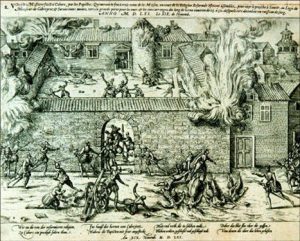

Coligny was thrown out of a window, finished off, cut into pieces and displayed in various places in Paris.

The story of Coligny’s murder according to Agrippa d’Aubigné in the Universal History: ‘Besme entered his room, and found the admiral in his night dress and asked him: “Are you the admiral?” The answer was “Young man respect my old age”…Besme drove his sword through his body and having drawn it out, cut his face in two. The Duc de Guise asked if he had done the job and as Besme answered yes, he was ordered to throw the body out of the window, which he did.’

Among the main Protestant leaders present in Paris, only Henri de Navarre and Henri de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, escaped the Saint Bartholomew massacres.

Elizabeth of England mourned for the admiral, Protestant German Princes were indignant, while Pope Gregory XIII and Philip II of Spain openly rejoiced. Indeed with the death of the admiral the Protestant camp lost a character who, thanks to his birth and to his diplomatic and warrior talents, carried the colours of the Reformation in Europe.

It should be said that the beautiful memorial at the temple Oratoire du Louvre in Paris, featuring the admiral and carved by Gustave Crauk (1827-1905), bears the wrong date of birth. It never was corrected…

The reigning dynasty in the Netherlands, the Orange-Nassau, are descendants of Coligny through his daughter Louise who married William I the Silent, stadtholder of Holland (1544-1584).

The monument in memory of Coligny

The beautiful white marble monument, at the head of the Oratory temple, rue de Rivoli in Paris, was created by the sculptor Gustave Crauk (1827-1905). Inaugurated in 1889, it represents the admiral standing in front of a window in memory of his defenestration.

It bears an erroneous date of birth. This has never been corrected…

The reigning dynasty of the Netherlands, the Orange-Nassau, descended from Coligny through his daughter Louise, wife of William I the Silent (1544-1584), Stathouder of Holland. Two sovereigns of the Netherlands, queens Wilhelmine and Juliana, came to the statue to honor the memory of their ancestor, respectively in 1912 and in 1972.