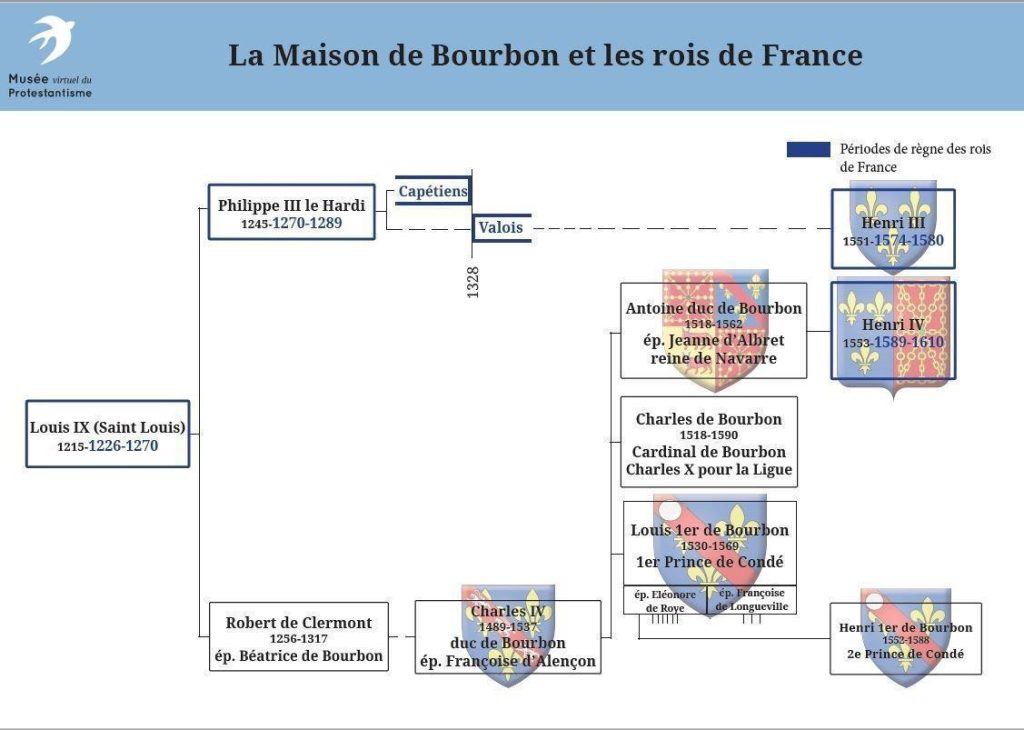

He was the head of a family with royal connections

Henry of Bourbon, second prince of Condé, was born in 1552. He was the son of Louis de Bourbon and Eleanore de Roye; his cousin was Henry of Bourbon, who later became Henry IV and head of the Bourbon family.

In 1572 he married Marie of Cleves, who died in 1574 without having any sons. In 1586 he married Charlotte de la Frémaille, who came from a distinguished Protestant family in the North of France. She had three children, including a boy called Henry, but who died in childbirth.

Little is known about the exact circumstances of Henry of Condé’s death in 1588. He was wounded in the battle of Coutras and was just regaining his health when he suddenly died without any apparent reason. Probably one of his enemies poisoned him but who could it have been? Perhaps it was either a moderate Catholic or a Protestant who was irritated by his extreme views? Finally the Princess of Condé was accused of the murder, together with her lover; she was arrested in her home in Saint-Jean-d’Angély.

Henry was a Protestant leader

Sadly, Henry of Condé did not inherit either his father’s charisma as a leader or his political talent. Above all things, he was a Protestant – his faith was dogmatic, austere and unyielding; in his eyes the success of the Protestant cause was all that mattered. What’s more, although he was nominally appointed head of the Protestants at the death of his father in 1569 (this became official in 1574) because Henry of Navarre had to remain at the royal court, he was soon replaced by Gaspard de Coligny a military leader and Henry of Bourbon Navarre, first prince of the blood, who both took on the leadership of the Protestant cause because of their strong personalities.

The Treaty of St Germain in 1570 brought the Third War of Religion to an end. Protestants were given a certain degree of religious freedom and some strongholds where they could be safe. Coligny was appointed as a member of the Royal Council and Marguerite de Valois, the king’s sister, became engaged to Henry of Navarre. This reduced even more the influence of the second prince of Condé over the Protestants.

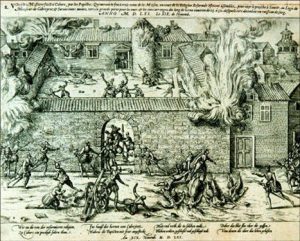

The kingdom was at peace until 1572, when the St. Bartholemew massacre took place. In the court of the Louvre Palace, the Protestants were put to death, their military leaders were assassinated; Navarre and Condé survived but only at the cost of abjuring their Protestant faith and being coerced into Catholicism. Condé spent the next two years at court; during this period the religious wars began again; he was with the king at the siege of La Rochelle.

At this time the Protestants in, the South established the Union of Provinces of the South of France. This structure sought to set up a State within a State so as to organise its own finances and diplomacy.

The king’s younger brother led a public revolt against those in power

The younger brother of the king, the Duke of Alençon, led a revolt in 1574 against the leadership of Catherine de Medicis; it was called the conspiracy of Dissatisfied Subjects. It provided just the opportunity Condé had been waiting for to escape from France into Germany. He raised 20000 soldiers (Reiters) under the command of Prince Casimir of the Palatinate, who came to join the Protestant army in their fight against the royal troops. At the Assembly of Millau in July 1574 he was appointed leader and general of the Churches of France by the Protestant supporters.

Condé was one of the Protestant military leaders during the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Religious Wars. He won renown for seizing the town of La Fère in 1579, although it was lost to the royal troops the following year and also Angers (1585) which was also lost a fortnight later, forcing Condé to flee to Guernsey.

In 1587, he accepted the authority of the King of Navarre, the Bourbon leader, and also his cousin. However, there were many violent disputes between them over the real reason for opposing the Crown. Condé only wanted to make Protestantism the official religion in France. However, the situation was different for Henry of Navarre, heir to the throne. It was more important for him to obtain peace in the kingdom and not necessarily a protestant supremacy. Sadly, this lack of unity weakened the Protestant army.

A forgotten prince

Regretted by his contemporaries he shared their passion and he seduced them by the strength of his convictions.

Agrippa d’Aubigné said the second prince of Condé was a brave, determined and inflexible warrior but he was also narrow-minded, sometimes lacking in judgement and did not possess the King of Navarre’s unusual capacity to have an overall view of any given situation.