His life

He was born in Madrid in 1925 into a Spanish Protestant family, and his family name was his Danish grandfather’ on his father’s side. His father Enrique Lindegaard (1879-1944) was a pastor at the El Salvador temple in Madrid, and also chaired the Spanish Evangelic Church. Eduardo Diaz Yepes (1910-1978), his uncle on his mother’s side, was a renowned sculptor in South America.

In 1938, during the Spanish civil war, his family migrated to France at Clairac (Lot-et-Garonne), and was accommodated by pastor Jacques Delpech (1887-1965).

In 1942, Lindegaard was 17 and he studied at the Cevenol secondary school in Chambon-sur-Lignon (Haute-Loire); he was already fascinated by painting and poetry. At the house of Roches, a hall of residence for refugee-students, he escaped being rounded up by the Germans on 29 June, 1943. He was deeply affected by the war background while growing up, by his life as a refugee, and by his father’s premature death in 1944. In 1945 while studying at the theology school in Montpellier, Lindegaard attended Beaux-Arts classes as well.

The dialectical theology of Karl Barth (1886-1968), focused on the person of Christ, and the Christological interpretation of the Old Testament by Professor Wilhelm Vischer (1895-1988) decisively inspired his work as a pastor and as an artist.

After 1952 Lindegaard was a pastor in the Gard region. In 1956 he married Béatrix de Rougemont and they had three children. In 1958, Jean Delpech ordained him to the pastoral ministry. Until 1982 he was a member and then chairman of the liturgy commission of the Reformed Church. In Vézenobres his part-time ministry enabled him to pursue his artistic vocation.

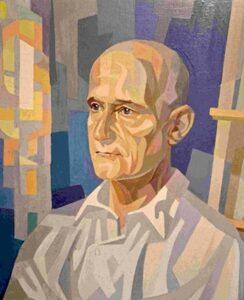

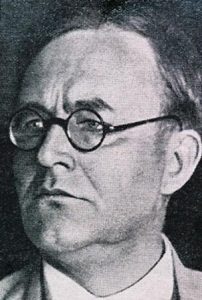

His acquaintance with the cubist theoretician Albert Gleizes (1881-1953), he had met in 1952, increased his training. Albert Gleizes turned Catholic late in his life and became interested in religious art. They talked about religion and art. Though he was influenced by Gleizes, Lindegaard developed his art with his own aesthetics which progressively evolved into a more and more poetic and stylised expression. Later on, he was renowned for his watercolours -mainly landscapes -, his portraits, and his Biblical drawings in black ink.

Lindegaard stopped his pastoral activity in 1990 and withdrew in the Mas Soubeyran near the Musée du Désert (Gard). Since the 1960s he lead watercolour workshops. In 1996, he died at the Lazaret in Sète surrounded by his watercolour trainees, and left an almost completed watercolour of the cathedral in Maguelone.

A theology of the image

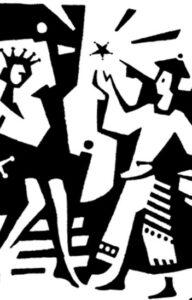

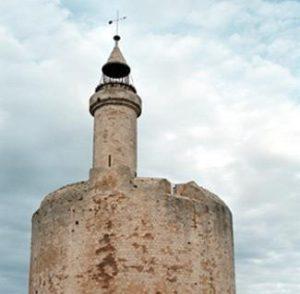

Olivier Tric (1936-2024), an architect and writer, mentioned the scientific structure of Lindegaard’s black and white drawings, and the genuine and unrivalled contribution they all made to art history. He especially noted the visual craftiness, intelligence, and the evocative capacity as well as their internal precision and potency. He also identified a major stylistic invention, i.e. including nested figures within a central figure. For instance in A Voice in the Desert, under the lifted arm of John the Baptist the bright figure of Christ can be seen, and announces his coming; in At the Constance Tower, the Protestant women prisoners, gathered around the edge of the well on which the word had been engraved, also form the fingers and palm of Christ’s pierced hand.

In his Biblical art, Lindegaard also unobtrusively used signs and symbols to be seen only on careful scrutiny. For example in the text with the drawing featuring the Magi in front of King Herod, Lindegaard invites us to see the pictorial link between Herod’s crown with five points, each with a pearl, and the similarly adorned star. We are thus made to meditate on the difference between ephemeral temporal power and spiritual power: ‘There is a link between the star and Herod’s crown. But the crown will fall whereas the star is firmly in the sky. The star can be pointed out, its light can be received, but it cannot be got hold of: it is for all men and for all times.’

Lindegaard explained his work as a search for a refined style progressively rid of incidental details, in his drawings, watercolours or his sermons: ‘Throughout my ministry I never wanted to dissociate what could be heard from what could be seen. But I distrusted images that depict, confine and immobilise. I merely drew signs expected to be significant to point, like John the Baptist’s finger, to the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.’

The Bible of contrasts

In 1993, Lindegaard gathered his Biblical black ink drawings with the texts explaining them in The Bible of contrasts: Meditations by pen and line. Combining the sober black and white contrast and the original, expressive and energetic, sometimes dramatic graphic style often full of motion, grabs the attention and makes us reflect. The texts point out details in the drawings and alternate description, narration, dialogue, poetry, prayer and sometimes even with humour or irony. The book came into being thanks to a subscription launched by pastor Jérôme Cottin, and presented a synthesis of Lindegaard as a pastor, a writer and an artist. When it was published in German, Jerôme Cottin said: ‘The rare fact that a theological or spiritual French piece of writing was translated into German is a noteworthy success […] That means that it meets a need: the need for quality spiritual works, the need for an easily replicable black and white Biblical visual material, and the need for catechetical documents for teenagers and youths as well as for adults.’

The drawings and texts from the Bible of Contrasts still circulate in Europe, in America and Indonesia under various formats.

Some temples and community centres are adorned with Lindegaard’s works:

• Easter Lamb – mosaic in the temple at Aubagne (Bouches-du-Rhône);

• Fire Bird – mosaic in the Protestant student hostel in Montpellier (Hérault);

• Children in the hands – mosaic at the Centre Arc-En-Ciel (Rainbow Centre) for handicapped children in Nîmes (Gard);

• Christ in Majesty – mural painting at the temple in Saint-Dié (Vosges);

• Drawings from The Bible of Contrasts as mural tapestries by Daniel Bourguet, some of which are exhibited at the Communauté de Pomeyrol in Saint-Etienne-du-Grès (Bouches-du-Rhône);

• He is risen, a drawing from The Bible of Contrasts enlarged and exhibited at the entrance of the Protestant Centre in La Rochelle;

• Translucent prints of drawings from The Bible of Contrasts on window panes in the church at Abbenbroke in Holland.

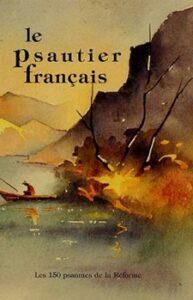

Lindegaard’s works also illustrated several books on religious practice and contemplation, for instance The Pilgrim’s Psalm (1998), and The French Psalter – the 150 psalms of the Reformation (1995), among others.

Lindegaard also made multiple versions of the Huguenot Cross in pewter.