His youth, his studies and early political leanings

Jacques Ellul was born on 6th January 1912 – his father was orthodox and his mother protestant. He was a brilliant pupil at the Lycée Montaigne (now called the Lycée Montesquieu) and then he studied law at Bordeaux university. During his time there he was converted to Christianity but his preference for Protestantism came at a later date

He became friendly with Bernard Charbonneau (1910-1996), who was also a student at Bordeaux university. The two friends began to start up “press clubs” and discussion groups around the themes of scientific progress and the changes which came with it. This movement could be described as ecological before its time – the two friends were enraged by the helplessness of political parties when confronted with the power of technology ; they also organized camps for the student organization called the “Fédé” (Fédération Universelle des Associations chrétiennes d’étudiants).

After his doctorate viva in 1936, Jacques Ellul was a lecturer in the University of Montpellier (1937-1938) and then law professor in Strasbourg (1938-39).

He then published his first articles in the protestant press (Le Semeur and Foi et Vie) and entered into a theological debate with Suzanne de Dietrich (1891-1981).

The Vichy government dismissed him in 1940 because he was the son of a foreigner (his father was born in Malta), so he tried to earn his living as a farmer and became an active member of the Resistance movement, although he never actually took up arms against the enemy. He passed on information to the Maquis, took in prisoners on the run and Jews hunted down by the Germans. He managed to obtain false papers for them so that they could escape to the free zone.

In 1943 he took the “agrégation” exam in Roman law and history of law ; he was then appointed Professor in the Bordeaux law university, where he taught until his retirement in 1980.

Like so many of his generation, he was deeply distressed by the failure of the Front Populaire as a political party, by the threat of Nazism and the onset of the war. This is why he wanted to take up politics and he participated enthusiastically in the preparation of the general election of October 1945. He became a member of the Union Démocratique et Socialiste de la Résistance (U.D.S.R.) but his party did not manage to obtain 5% of the votes in the Gironde so they were unable to have a seat in parliament.

A committed protestant

Ellul was disappointed by the fact that the traditional political parties had returned to power. This is why he became a more deeply committed protestant – in his view Christianity could really contribute positively to the modern world.

He began to write for Réforme, a review which started in 1945, and Foi et Vie. In 1947 he was elected delegate for the reformed churches of Béarn, Dordogne and Guyenne at the National Synod of the Eglise Réformée de France (E.R.F.). In 1956, he was elected member of the National Council of the E.R.F.

He was a founder member of Le Protestant d’Aquitaine, a monthly review.

In his local Church, he organized a service every month in his own home in Pessac and with his friend Yves Charrier he founded one of the first Youth Clubs, with the aim of warding off delinquency.

With pastor Jean Bosc (1910-1969) he founded the Protestant Professional Association in order to help Protestants conciliate both their professional and Christian commitments.

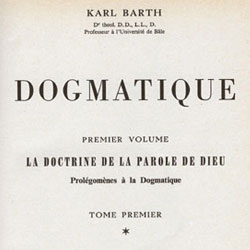

It was Jean Boscwho enabled him to discover the works of Karl Barth. At his death in 1969, Jacques Ellul took over from him as main editor of Foi et Vie until 1986.

In every institution he joined, he would bring with him a note of non-conformism : although he wanted to reform Protestantism, he only managed to obtain the partial reform of theological studies in 1973 and that was only after much discussion.

He was on very much the same wavelength as the student movement in 1968, but he later drew back from it because he was shocked by the excessive behaviour of those who claimed they were leading a “proletarian revolution” ; rather, he tried to mediate between the government and these “angry young men”.

In his native region, with his friend Bernard Charbonneau, he sought to discourage the interministerial commission set up to develop mass tourism on the Aquitaine coast which would entail the arrival of the inevitable motorways, hotels, supermarkets etc.

A truly modern approach

Jacques Ellul was a truly original thinker because he criticized modern society vehemently, he thought it was too dependent on technology and its by-products : the various different means of communication and advertising.” Publicity encourages man to no longer value his own experience or personal reasons for making decisions : instead, he follows the sociological trend of his time… Modern means of communication are very efficient but at the cost of authenticity, quality and any normal relationship between human beings”.

According to Ellul, industrial production controlled man’s true needs, forcing him to consume more than he either wanted or required.

He refused to accept any kind of political or philosophical system because he defended the individual against the State, freedom against conformity and a meaningful, rewarding life against crass materialism. In his many articles and books he continually denounced political illusions and the danger of naïvely believing in the ideals of both Marxism and liberalism.

According to Ellul, a rich world bursting with inventions still held little value and prevented us from understanding that “the only true moral action is to believe in the Resurrection”.

However his message was only partially understood and is was due to the fact that he was greatly appreciated abroad, particularly in the States, that Jacques Ellul was finally recognized in France.