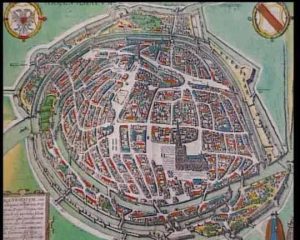

Sturm at the Strasbourg council

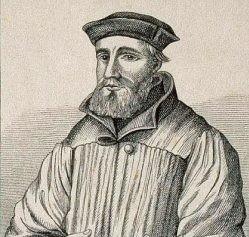

Jacques Sturm belonged to a noble and ancient family in Strasbourg which included religious men as well as political figures. Jacques Sturm, like them, repetitively held honorary positions, such as Stettmeister (President of the city council), but he was first and foremost a member of the council of the XV (domestic affairs) and the council of the XIII (foreign affairs).

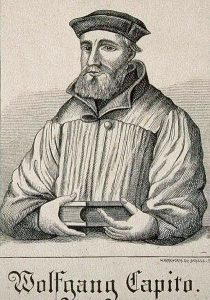

He was first interested in a clerical career, and spent three years at the Faculty of Arts in Heidelberg, then he studied theology in Friburg where he met Wolfgang Capiton and Matthieu Zell. Back in Strasbourg in 1509, he was part of a humanistic ‘ sodalité ‘ (society) where he met Erasmus in 1514, who considered religion to be a matter of personal conscience. That meeting and the reading of his writings drove Sturm to turn to antique literature, to the Bible, the Fathers of the Church and to humanism in general which stressed pedagogical renewal. It seems that he read Luther’s writings around 1520.

In 1523 he relinquished his clerical status at the service of the provost of the cathedral, and entered politics to be elected member of the city Council. In a few years he emerged as the leader of the city and played a key role in the Empire’s affairs.

Sturm and the Reformation

The Evangelical movement reached Strasbourg in 1520 under the influence of Matin Zell, bishop of the cathedral. Catholic worshipping progressively changed, and clerics married. As early as 1524 most Council members tended to support the Evangelical trend, generating tensions due to the interweaving of religions life and institutions: Who could decide on reforms, were they compatible with the laws of the Empire and with the condemnation of Luther in Worms in 1521, then what should be done about those who remained faithful to traditional forms or conversely wanted more radical reforms?

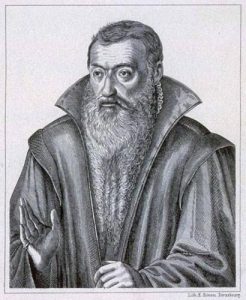

The exercise of control, also in ecclesiastic matters, had to be clarified. After troubled times, the closing down of convents, and uncontrolled initiatives by some Evangelical preachers, Sturm the patrician, decided that affairs dealing with religion and their institutions, should come under the exclusive control of the city’s authorities, and not left to the people or the ministers. He was true to Erasmus’ more conciliatory attitudes, and was in favour of religious pluralism i.e. temporarily keeping mass. But the discords in the initial years, the struggle against the Anabaptists, the failure of his conciliatory endeavours during the peasants’ war, all prompted a more severe attitude. For him, the civilian authorities were responsible for the city and its unity, but the Council’s power was over the Church and its doctrine too. Sturm reminded the preachers that their role was to spread the Gospel, and not to provide guidance to the Council.

He presided the 1533 synod during which Martin Bucer‘s text was adopted, banishing the Anabaptists and other religious dissidents.

He was interested in education and presided over the school commission until he died. Elementary schools were modified and a college created to train ministers. He asked Jean Sturm (a homonym, but not a relative) to come to Strasbourg and become the rector of a High School, later called “Gymnase”, one of the most influential schools in Europe.

Sturm the diplomat

In 1524, Sturm married the daughter of a stettmeister and thus increased his influence after he was elected to the two councils – XIV and especially the XIII devoted to foreign affairs, complemented by his appointment as stettmeister in 1526.

His statesman’s stature established, he took charge of most of the external affairs of the city. He represented Strasbourg at the first diet in Spire in 1526, which temporarily gave freedom of worship to princes and free cities. Then at the diet of 1529, confronting the Emperor’s pressure against the Reformation, five princes and representatives of fourteen cities, Strasbourg included, presented a solemn protest against the decree proposed by the Emperor.

Faced with the risk of armed repression against the Evangelical confession, the need to be armed to resist implied alliances. Turning to the free cities of the Empire was impossible, though their rights were often defended at diets, because the cities, in spite of their unity, were too weak to resist imperial troops, even more so as some had not joined the Reformation.

At the colloquium in Marbourg in 1529, an Evangelical alliance was forged between Swiss cities – Zurich, Basel and Bern, Philip of Hesse and John of Saxony -, and the cities Nuremberg and Ulm. But it was fragile, given the differing conceptions of Luther and Zwingli about the Eucharist. The quarrels with Saxony brought to the foreground the alliance with the Swiss, within a “right to Christian middle class fellowship” each vowing to support the others in case it was attacked on faith grounds.

At the diet of Augsburg in1530, Charles V was opposed to the Protestant princes in Northern Germany, and refused the Confession of Augsburg, the founding text of Lutheranism. Strasbourg did not concur with it. Martin Bucer wrote a specific confession of faith for Strasbourg, the tetrapolitan Confession.

When the Smalkalde League was founded in 1531-1532, theological differences with the Lutherans being were tolerated and Strasbourg was accepted in the League that lasted fifteen years. For Sturm the only aim of the League was to defend and spread the Evangelical faith, contrary to Zwingli who considered war legitimate in order to establish religious free choice in the Catholic Swiss cantons. Sturm was also opposed to the wars of aggression of the league in Wurtemberg and in Northern Germany, which created conflict with Philip of Hesse.

But the conflict with the Empire became inevitable. Charles V destroyed the League at the Mühlberg battle in 1547. Strasbourg was threatened, the choice was to capitulate or to resist: Bucer and the preachers were against capitulation and asked that the people be consulted, which Sturm refused, but he pleaded for negotiations. He yielded to the “interim” proclaimed by Charles V, who imposed the return to Catholicism, but obtained a few concessions (celebration of the Lord’s supper, priests’ marriage) while waiting for the decisions of the Council in Trente. Sturm pledged allegiance, negotiated with the bishop who demanded that Martin Bucer leave; the concessions were annulled ten years later, thus allowing Strasbourg to save the Evangelical faith.