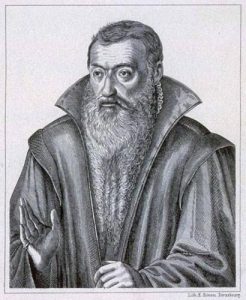

Jean Sturm was a politician and teacher

Jean Sturm was born in Schleiden in Westphalia in 1507. He studied first at Liège university (1521-1524), then at the famous “College des Trois Langues” at Louvain University (1524-1529).

In 1529, Sturm came to Paris, where he taught at the Collège Royal, recently set up by king François Ier (it is now called the Collège de France). He specialized in rhetoric and dialectics.

He spent his time either working hard in the university (he published various works including commentaries on the classics, especially Aristotle and Cicero) or else he was sent on political assignments by the French court.

Diplomatic assignments

He strived for religious peace and supported François Ier in his efforts to reconcile France with the Protestants in Germany. He wanted to see the Reformation movement take place, but on one condition, that a spirit of tolerance should prevail towards each religion.

He stayed in close contact with those of the reformed faith in France and was careful to maintain their freedom. However, he also worked at reconciliation between Protestants and Catholics and unity between different reformed Churches.

However, due to his defence of the Reform movement, it became dangerous for him to continue living in Paris so he decided to go back to Strasbourg, the heart of European humanism, in 1537.

Charles Quint’s victory over the German protestants in 1547 forced Sturm to leave politics for good and from then on he devoted his time to teaching and nothing else.

The foundation of the Strasbourg "Gymnase" (1538)

In March 1538, the Strasbourg chief town councillor asked him to completely reorganize education at a local level, which was a major task as this town had recently joined the Reform movement. Jean Sturm tried to create a balance between moral and religious education on the one hand and culture and intelligence on the other.

His plan to reorganize primary and secondary education was accepted and the “Gymnase” (secondary school) came into being – he was shortly after appointed headmaster. He also laid down the basic structure of higher level education – this later became first the Haute Ecole and then in 1566, the Académie de Strasbourg, of which he was the rector until 1581.

The theological controversies of Strasbourg

During the years 1571-1575, Jean Sturm took part in theological controversies between members of the Lutheran and reformed faith. He himself took up the cause of the Reform movement and protected their Church in exile in Strasbourg. He was not in agreement with the orthodox Lutherans, notably Jean Marbach (1521-1581), a professor of theology, or Jean Pappus, (1549-1610), who was another professor of theology in the Strasbourg Académie. Sadly, his controversy with him took such a violent turn that in the end he had to stand down as rector in 1581.

His works

Jean Sturm was a prolific writer. His works fall into three categories :

- Firstly, he published classical texts and in particular the works of Cicero (1540-1541). Then came translations from Latin and commentaries on a selection of classical texts, one of which was the speeches of Cicero.

- Secondly, in a completely different sphere, there were his educational and teaching programmes, with advice for the teachers. He also wrote textbooks for the “Gymnase” and other documents of use to the school administration and teaching syllabus.

- Lastly, his treatises on rhetoric and dialectics, which were his true speciality.

Jean Sturm was an educational theorist and a teacher

Jean Sturm’s educational and teaching theories can be mostly found in Classicae Epistolae, published in 1565. These letters were to be a series of helpful instructions for teachers to follow.

Here are the main ideas of this work. Psychological factors were of the utmost importance.

Indeed, intellectual and moral teaching formed part of a whole, according to him.

Jean Sturm was particularly concerned with the youngest pupils. He did not impose any rigid method but thought it was important that pupils should cover a lot of ground at quite a sharp pace, without, of course, being overworked. For him, memory work was also important – he had conceived some fairly difficult exercises in this field, which were not, however, beyond the children’s reach. His educational system was based on an ideal of balance, which would enable a pupil to later develop his full potential. Indeed, this ideal of balance pervaded all his educational concepts.