Circumstances upon signing

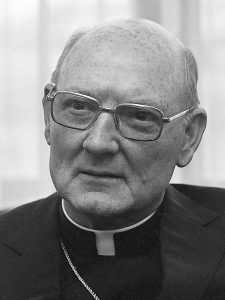

Cardinal Edward Idris Cassidy (1924) © Wikimedia Creative Commons

Cardinal Edward Idris Cassidy (1924) © Wikimedia Creative Commons

Évêque luthérien Christian Krause

Évêque luthérien Christian Krause

The declaration was the result of discussions between Lutherans and Catholics initiated in 1967, referring to many documents among which Are 16th century anathemas still valid? (1986)

It was completed in 1997, presented in 1998 and officially signed on 31 October 1999, the anniversary date of Luther’s 95 theses posting in 1517. The city of Augsburg in Germany was chosen with reference to the confession of Augsburg, the founding text of Lutheranism subjected to Charles V in 1530.

The signatories were Cardinal Edward Cassidy, president of the pontifical council for promoting Christian Unity and Bishop Christian Krause, president of the lutheran World Federation.

The original document was written in German.

The declaration was also signed by the Methodist World Council in Seoul (Corea) in 2006.

The World Communion of Reformed Churches (WCRC) and the Anglican Communion signed in 2017.

The issues

A differentiated consensus was reached whilst various different interpretations remain.

The subject of the declaration itself is of particular interest: justification by faith was a major cause of divergence between Catholics and Protestants since the Reformation.

The declaration is presented as a step towards ecumenical intercommunion, which shows a willingness to pursue the dialogue.

The place and date of the signing as well as the quality of the signatories emphasize the symbolic nature of the declaration.

Content of the common declaration on justification

Cardinal Edward Idris Cassidy et Évêque luthérien Christian Krause © Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Cardinal Edward Idris Cassidy et Évêque luthérien Christian Krause © Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The text comprises a preamble and five chapters consisting of 44 articles.

The preamble, in article 1, recalls that ‘doctrinal condemnations were put forward both in the Lutheran Confessions and by the Roman Catholic Church’s Councile of Trent. These condemnations are still valid today and thus have a church-dividing effect.’

But in article 5, the preamble specifies that ‘the remaining differences are no longer valid for doctrinal condemnations.’

Chapter 1, the biblical message of justification explains the meaning and justification based on Biblical verses, especially from Paul’s epistles: justification is forgiveness of sins, union with Christ, and is given by God alone by grace through faith in the Gospel.

Chapter 2, the doctrine of justification as an ecumenical problem, explains that a common understanding of justification allows to resume an ecumenical dialogue on the truth of this doctrine.

Chapter 3, the common understanding of justification, explains the consensus reached: ‘Together we confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works.’

Chapter 4, explicating the common understanding of justification is at the heart of the document. It comprises seven sub-chapters with three articles each expressing the consensus ‘We confess together that…’and both points of view of the Lutherans and the Catholics.

The seven sub-chapters are entitled:

- human powerlessness and sin in relation to justification

- justification as forgiveness of sins and being made righteous

- justification by faith and through grace

- the justified as sinner

- law and Gospel

- assurance of salvation

- the good works of the justified

The consensus is that good works (Christian life lived in faith, hope and love) follow justification and are its fruits. That’s why Christians are admonished to bring forth the works of love.

According to Catholic understanding a reward in heaven is promised to these good works which contribute to growth in grace. Lutherans view the good works of Christians as the fruits and signs of justification and not as one’s own merits.

Chapter 5, the Significance and Scope of the Consensus Reached puts an end to doctrinal condemnations about justification and lists the doctrinal points which need further clarification. The declaration on justification offers a solid basis for pursuing the clarification of these remaining points.