When the skies talk about the world and the future of its inhabitants...

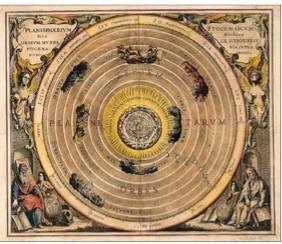

Prophecies “deduced” from the paths of the stars are part of a very ancient tradition – probably part of life in any community. They were mentioned by the Chaldeans, Egyptians, Mesopotamians, as well as in time-honoured societies, and also in the debates they gave rise to, led by the great personalities and prophets of Israel, such as Joseph, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, etc. The prophecies were based on multiple day and night observations of the heavens : the changing position of the sun and the moon, the fluctuations in brightness of the planets, and their paths within constellations, the trajectory of comets, the appearance of new stars, etc. All these fascinating components were used to draw up maps of the heavens and they then given names. These data enabled setting of time markers which were used to organise daily life : day, night, time to sow, time to harvest, weather-related disasters, and other ways of controlling the natural environment according to the observations.

Observing the heavens raises a lot of puzzling and hard-to-answer questions

The first astronomers who observed the sky saw regular features, fixed stars, time markers, but also movements and discontinuities, which raised a lot of questions leading to astrological speculation. Mythological texts raise a wide range of fears which were fuelled by these speculations ; natural disasters, epidemics, tragic destinies, fatalities, predeterminations, and other severe judgements man seems unable to escape.

After Ptolemeus, astronomy developed within Islamism, a fact mentioned by Calvin, and knowledge has not stopped growing ever since.

The beginning of the Renaissance was the time when Galileo’s telescope enabled subtle and significant observations that encouraged a mathematical approach, which allowed, among other things, the calculation of orbits. Astronomy could then no longer back up accidental fatalities that had made astrology so successful. But philosophers who had understood and spoken their minds accordingly, such as Marsile Ficin, Savonarole and, a little later, Giordano Bruno, were harshly condemned by the Church.

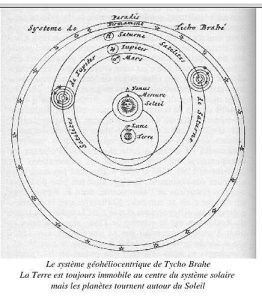

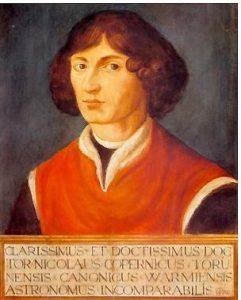

So the ambiguity still lingered, and great astronomers like Nicholas Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) and Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) in the late 16th century, had to claim – especially to their patrons – that they were astrologers, and used this to justify establishing calendars with reliably fixed religious celebrations.

Judiciary astrology totally disappeared with Newton (1642-1727). It lasted, along with prosperous horoscope making, only as a private business, but did not benefit from advances in astronomy.

The battle of astrology in the 16th century : a critical point for the Reform movement

In the 16th century almanacs, horoscopes, birth charts, i.e. portrayal of astrological circumstances on the occasion of a birth. These texts became easier to circulate with the development of printing.

Some of these poetic tracts, anthologies or poems more or less supported the new evangelical trends, and were a meeting point for opinions, but stressed evangelical hope rather than risky predictions.

François Rabelais is known to have written many almanacs of that kind : To the kind reader, Greetings and Peace in Jesus Christ. Considering many an abuse, in the shadow of a glass of wine, the source of lots of Louvain Prognostications, I myself have calculated one more reliable and sure than any seen so far, as shall be proven by experience. (The 1553 almanac, published after the Placards affair)

Clément Marot was the writer of many birthday horoscopes :

Come boldly, & do not fear that Saturn should disturb your worldly ways, for you will be born, not poor & thin as I (alas !) but the child of a great Prince. So you will have (God providing) the true means to obliterate boredom, The true means for prolific enjoyment, Through Jesus Christ who vanquished death triumphantly. So come little child (Eclogue upon the birth of Monseigneur le Dauphin’s son, 1544)

Other writings used astrological predictions for the benefit of the Roman Church. Referring to dramatic events – Henri II’s death for example – they explained it as a judgement of God announced in the stars. And they also used them to predict other impending disasters, in case evangelical trends and Calvin’s writings should have disciples. Nostradamus’ prophetic writings, cryptic as they may be, were extensively used that way too.

In this context Calvin intervened with all his energy and remorseless irony and wrote his Treatise or warning against astrology called judiciary and other peculiarities ruling the world today.