The beginnings

In 1895 in Vadstena (Sweden), John Mott (1865-1955) lay down the foundation of the international student movement which soon had a large audience among Christians of all persuasions. It was called the World Christian Student Federation. Soon after, in 1905, the movement was open to women at a time when mixed activities were very rare. A branch was open for young adults – in France called the post-fédé – that later joined it.

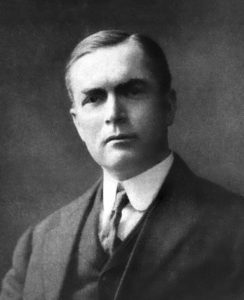

John Mott (Nobel Peace Prize 1946) was born in a militant Methodist family. He studied History at Cornell University (New York) and was involved in the local branch of the YMCA, to which he soon devoted all his energy. In 1888 he became national secretary. In those days most Western universities were involved in reformations to enrich and diversify their training courses. John Mott took up the opportunity to develop YMCA groups and to offer students biblical and ethical training to further their studies towards assuming responsibilities. He was then in contact with other student associations working on similar projects. He wished to assemble the various groups and associations with a common ecumenical demand. The different approaches, far from being an impediment, seemed to him a good way of testing the respect for others in a plural and interdependent world. Ever since the beginning, the multidisciplinary approach was chosen when organising the work.

John Mott was Secretary General of the WCSF until 1920, and then President from 1920 to 1928.

The WCSF set up its headquarters in Geneva where the YMCA’s already were, as well as those of the Red Cross. Later on a number of international organisations also had their headquarters in that city, namely the League Of Nations (LON), the International Labour Office (ILO), the World Council of Churches (WCC).

Immediately after the WCSF was created, several national federations emerged.

The British branch, Student Christian Movement (SCM),was created in 1895, on the initiative of a young Irish pastor, Tissington Tatlow (1876-1957). It was immediately set up in Oxford and Cambridge. It appealed to many students, some of which later had important responsibilities in the lives of Churches and played a key role in ecumenism, namely Ruth Rouse (1892-1956), Joseph H. Oldham (1874-1964), William Temple (1881-1944). The SCM helped many foreign federations to discover the Anglican liturgy, to translation problems and to a pragmatic approach of social problems.

The German branch, Deutsche Christliche Studentvereinigung (DCSV), was created in 1897 in the dynamic academic community with numerous students associations. Pastor Hans Brandenburg was its first secretary general. In the interwar period the people in charge and the students of the DCSV played a key role in spreading Karl Barth’s thought. He was then professor at Göttingen university. Some worked in the ecumenical group ‘Faith and Order’. Most of them signed the Confession of Barmen in 1934 and were involved in the confessing Church, such as Reinhold von Thadden (1891- 1976), Martin Niemöller, Hannes Lilje (1899-1977) and of course Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945). The Nazi regime banned the DCSV in 1938. However, it still continued to exist secretly within the WCSF. After 1945 many of its membres were present in the Evangelische Studentingemeinde (ESG), in the evangelical academies and the Kirchentag meetings from 1949 to 1989, which enabled students in the FRG and the GDR to meet regularly.

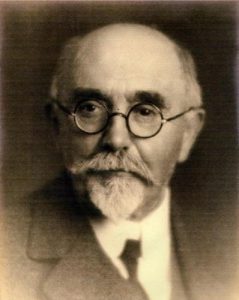

The French branch (Fédération française des Associations chrétiennes d’Étudiants) was created by the dean of the Protestant faculty of theology, Raoul Allier (1862-1939). Groups of the YMCA soon joined as well as the society of Protestant students in Paris and a few others, mainly of Protestant origin. Later on Jewish and Orthodox students also joined, and some openly agnostic ones too. Charles Grauss was very active by promoting meetings, enabling to buy land in the Hautes Alpes and on the Ile d’Oléron for holiday camps, and creating a magazine.

In the early 20th century national federations existed in the Netherlands, in Switzerland, in India and in China.

The WCSF had its own magazine World Student, relayed by national magazines, for example in France it was the Semeur (Sower) and for secondary school students Notre Revue (Our Magazine).

The first commitments before World War I

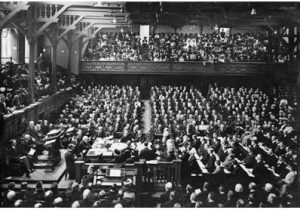

John Mott and other leaders of federations attended the Conference in Edinburgh in 1910 where Protestant Churches of various denominations met to design a missionary project to evangelise, at a time when colonisation politics were developing and in confrontation. John Mott’s talks insisted on reaching a fuller understanding of others thanks to the will to respect them. The WCSF played a key role in ecumenism and largely contributed to Faith and Order as well as Life and Work groups.

In 1913, some missions societies required more commitment from their staff, the WCSF created Volunteers for Christ ( a community-lifestyle). The men and women who committed themselves to it took a vow of celibacy. Suzanne de Dietrich (1891-1981) in France, Ruth Rouse (1872-1956) in England were among the first members. They became itinerate secretaries for the WCSF, thus promoting the life of local groups and organising meetings.

Suzanne de Dietrich, after studying engineering, became interested in theology. She developed biblical studies for students groups. In 1936 with Madeleine Barot they created the inter Movement Committee to assist refugees, that became the Cimade in 1939.

Ruth Rouse, after studying Sanskrit and theology, created groups in several countries, notably in India where she travelled widely. She became John Mott’s closest associate.

The effervescent interwar period

During World War I Churches were confronted with nationalistic uprisings and divisions. At the end of this long and murderous period, as borders were drawn up again and migrating movements increased, political and ethical questions were raised in many places and especially in academic circles. The WCSF and its various entities were confronted with these problems on the local and international level.

On the local level it supported common readings, interdisciplinary encounters – philosophy, history, literature, mathematics- in an international context. Some students came from Russia, others had fled from anti-Semitism in Central Europe, from countries where Jews were forbidden access to academic positions. Karl Barth’s works were studied and soon translated into English and French, and significant questions about dialectical theology were raised. Orthodoxy, Judaism and philosophy were studied.

Ecumenical meetings were numerous during that period.

In 1927 the group Faith and Order met in Lausanne which triggered a violent reaction from the Vatican (the encyclical letter Mortalium animos of 1928). It refused any talk with the Protestant and Orthodox circles.

In contrast meetings in Oxford and Edinburgh in 1937 the groups Life and Work and Faith and Order came closer together and eventually decided to create an ecumenical Council of Churches.

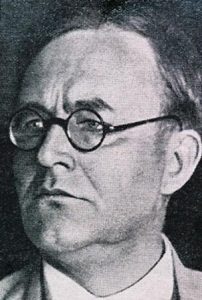

Thanks to the leaders, namely the pastor Pierre Maury, pastor Visser’t’Hooft and others, such as Reinold von Thadden, bishop of Lilje in Germany, JH Oldham, bishop Temple, the unflagging Ruth Rouse in England, links were developed and strengthened, the solidarity between the various national and international entities was rendered stronger.

This accounts for the active part played by many federalists – men and women – at the synod in Barmen in 1934, where the Confessing Church was created in Germany and committed to resisting Nazism. They signed the Pomeyrol Theses in 1941. They contributed to the Declaration of Guilt of the German Church in 1945 called the Stuttgart Confession. They were also active in the work of constituting the Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948. Later on a number of Secretary-generals and people in charge were ‘committed federalists’, such as W. Visser’t’Hooft, Philippe Maury, Philip Potter, Konrad Raiser, among many others.

After World War II

After World War II the WCSF remained active in supporting secondary-school and university students. It took part in reconciling missions with Germany, for instance building the reconciliation Church in Taizé with young people from all over Europe, or rebuilding the cathedral in Coventry. It played its part in the student movements of the 1960s. Some federalists were included in the liberation theology that developed in South America after the Vatican II Council.

In the 1960s, however, at a moment when economic growth seemed steady, when the idea that democratic involvement was assured and the war threat of a Europe war averted, universities changed and the WCSF activities evolved.

But the WCSF maintained it’s links with other organisations and continuing it’s involvement in the federative adventure, i.e. the Ecumenical World Council of Churches, the Cimade in France, some commissions of the French Protestant Federation, Evangelical Academies in Germany, some British NGOs in universities – Oxfam, etc.