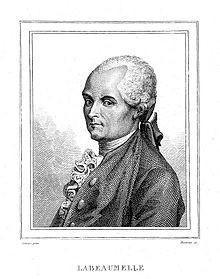

La Beaumelle studied theology ; then he went on to become a tutor, a teacher, a journalist and lastly, a writer.

He was born in Valleraugue in the Cévennes (Gard) ; his mother was a catholic and his father a protestant (the Angliviels had been protestants since the XVIth century). He was christened by the parish priest, according to the rules set out by the edict of Fontainebleau (1685). Then he studied at the college de l’Enfant-Jésus in Alès. However, when he returned to Valleraugue, he had a deep religious experience which resulted in his turning to Protestantism.

For this reason he decided to go to Geneva in order to study theology (1745).

Then he went to Denmark, where he was a family tutor and later, a teacher of French literature in Copenhagen.

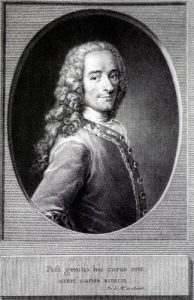

He came back to Paris in 1750, only to return to Copenhagen once more. From there he went on to Holland and finally Berlin (1751), where he met Voltaire.

His quarrel with Voltaire

La Beaumelle had violent opinions, was intellectually honest and not afraid of confronting others openly. He came into opposition with Voltaire and told him that many of the facts mentioned in his book Siècle de Louis XIV were purely superficial or inaccurate, while other subjects had not been treated. A quarrel between them ensued which soon developed into an affair of state and was very detrimental to La Beaumelle’s reputation.

Voltaire wrote Le Supplément au Siècle de Louis XIV, an attack against La Beaumelle, which was hastily countered by Réponse au Supplément du Siècle de Louis XIV. In this work, La Beaumelle, in violent terms, criticized Louis XIV’s religious policy. In particular, he was in disagreement with those responsible for the terrible sentence imposed on Claude Brousson, who had been condemned to the wheel. Voltaire had claimed, apparently, in his book that Brousson was a State criminal and not a heretic, because, according to him, the Cévenol prophets were rebels against the king.

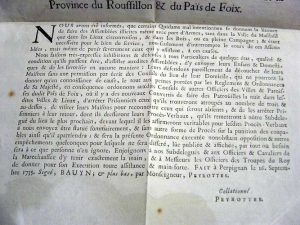

Voltaire publicly criticized La Beaumelle, who had nobody to stand up in his defense when he was thus accused of being a dangerous man whose writings attempted to undermine the Government. The situation degenerated to such an extent that, because of Voltaire, he was twice sent to the Bastille prison (in 1753 and 1757).

When he came out of prison, he was sent in exile to his native Languedoc. In 1758 he lived in Nîmes, the following year in Montpellier and he finally settled in Toulouse.

Between 1761 and 1762, he was one of the defendants of Calas.

He wrote on many varied subjects and was an advocate for tolerance

In the history of French literature, La Beaumelle holds a special place, as he was an intermediary between France and the countries of Refuge, enabling a cultural exchange to take place between the two.

He began writing at an early age. When he was 22 he started a periodical called La Spectatrice danoise ou l’Aspasie moderne (1749-1750), where he expressed disapproval of atheism and deism but advocated civil tolerance.

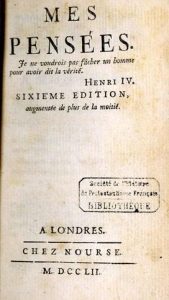

Three years later he published Mes pensées, ou Qu’en dira-t-on ? (Copenhagen, 1751). In this work, it is possible to see a link between La Beaumelle’s branch of Calvinism and republicanism, which was considered to be a major political heresy at the time.

Between 1755 and 1756, in Amsterdam, he published the 15 volumes of his Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de Madame de Maintenon et à celle du siècle passé, which were immediately successful. However, the subjects treated in both volumes were somewhat provocative and implicated well-known people, who, in self-defense, were liable to cause the author opposition and serious difficulties.

La Beaumelle contributed greatly to the court’s gradual acceptance of civil tolerance for the protestants ; he advocated freedom of conscience for all.

In L’Asiatique tolérant (1748), which was, in effect,” a treaty on tolerance” addressed to the king of France, Louis XIVth, La Beaumelle wisely concealed his true identity. In this work he set out to prove that to be tolerant was an essential quality for a Christian. He also insisted on the fact that the State would not be in a position to govern properly unless it had a policy of civil tolerance towards all its citizens. He advocated freedom of conscience for the French Protestants. He even went so far as to justify rebellion against a tyrant.

In the years 1762-1763, he corresponded with pastor Paul Rabaut and gave him assistance in drawing up the resolutions which would be discussed at the national synod in 1763.

His Catéchisme universel (1763) was never published – probably to avoid causing him any more trouble with the authorities. His aim in this work, which was set out in the form of a dialogue, was strictly limited to answering questions raised by the texts of the Scriptures.