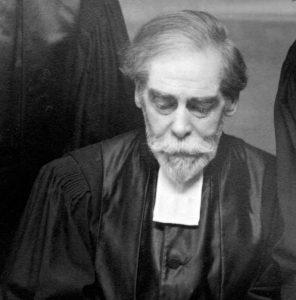

Biography

Louis Dallière was born in Chicago to a Catholic father and an Anglican mother. In 1921 he married Caroline Boegner, the daughter of Alfred Boegner, head of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society (SMEP).

After studying theology and philosophy in Paris and Harvard, United States (1915-1924), he was a pastor in Charmes, in the Ardèche region from 1925 to 1962, first with the ERE and, after 1938, with the ERF. In 1932-1933, he was a junior lecturer at the Faculty of Theology in Montpellier.

During the summer of 1932 he went to England to investigate the Pentecostal movement and devoted himself to promoting the Revival Movement within his Church. He was a passionate evangelist, and met Douglas Scott, a Pentecostalist. He was welcomed by the Free Church but not by the Liberals nor the Darbyites. In 1930 he became leader of the spiritual Pentecostal Movement at Charmes, in the Ardèche. In 1938 Louis Dallière encouraged the parishes of the Eyrieux valley to join the French Reformed Church. He was part of a Resistance network during World War II, and was recognised by Yad Vashem as “righteous among the nations” in 1990. In 1946 he paid homage to Wilfrid Monod, who had founded the Veilleurs (The Order of Watchers), and created the Union de prière de Charmes (The Charmes Prayer Community) – a national religious association which signed a treaty with the ERF in 1970. Louis Dallière founded the “Cours Isaac Homel” (Isaac Homel College), a secondary education establishment that ran until 1975.

His writings

- D’aplomb sur la Parole de Dieu. Courte étude sur le Réveil de Pentecôte (Steadfast in the Word of God. Short study on Pentecostal Revival), Charpin et Reyne, Valence, 1932 ;

- Le baptême en vue du retour de Jésus (Baptism with a view to Jesus’ return), s.d., “la réalité de l’Eglise” (the Truth of the Church) , ETR, 1927/2, p.395-441.

In the 1935 issue of Foi et Vie (Faith and Life), he had an article published on Le Protestantisme de nos jours et la doctrine (Protestantism of today and doctrine) showing how Protestantism had strayed from its roots since the 18<sup>th</sup> century, and could only survive by turning back to the core message of the Protestant Reformation.