The diffusion of the Reformation in Brittany in the 16th century

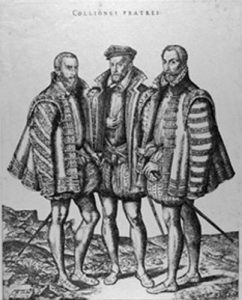

The Reformation took root in Brittany in 1558 when François d’Andelot, the brother of the Amiral de Coligny invited all the nobility in Brittany to his castle of La Bretesche in Missillac to listen to a Protestant sermon. He did all he could to have the lords interested in the new faith. The Reformed ideas were already present in Brittany, but on that occasion he overtly showed his sympathy or his membership. Calvinism spread in Brittany until 1565, mainly in the French-speaking areas. The Finistère region was less concerned for lack of Breton-speaking preachers.

The nobility was a significant component of the Protestant community, even the aristocracy, namely the Rohan and the Châtillon. More than a hundred noble families converted to Calvinism. They founded rural Churches. Urban Churches in Nantes,Vitré, Rennes, Guérande, or Morlaix consisted of middle class people and craftsmen.

The Saint-Bartholomew massacre had little effect in Brittany. Until 1585 few persecutions took place, undoubtedly thanks to the nobility’s protection. But in 1585 when the Governor of Brittany, the Duke of Mercoeur, took sides with the Ligue, everything changed and the Protestants were harried. Pastors left the region. Part of the nobility recanted, others joined the army of Condé. In 1589 after Mercoeur refused to obey Henri IV, the conditions worsened for the Protestants. Churches were scattered except in Vitré held by the Protestants. Vitré withstood Mercoeur’s siege, and was saved only when the Royal troops arrived. The Protestant nobility joined Henri IV’s side but many of them were killed in the clashes.

The conflict ended with the Edict of Nantes. Mercoeur surrendered to Henri IV, but Protestantism in Brittany was shattered. Moreover, the Edict was not favourable to Protestants in Brittany because worship was only authorised where it was openly practiced between 1596 and 1597. During Mercoeur’s rule Protestant worship was secret, except in Vitré. In Nantes, Rennes and Le Croisic however it was reinstated. The other Churches were fief churches around Protestant noblemen, terribly weakened by the struggle against Mercoeur. The Protestants were not granted any stronghold in Brittany but had a few Wedding Places.

The decline of protestantism in the 17th century

In 1611, the 20-year-old Henri de Rohan, succeeded Coligny, Condé, and Henri de Navarre, and headed the Huguenot movement. In 1621 he led the uprising of the Protestants against King Louis XIII but was defeated by the Royal troops and had to submit to the King. It put an end to the Huguenot movement. His mother, Catherine de Parthenay, a fierce Huguenot, supported the resistance of La Rochelle during the 1628 siege. But two generations later the Rohan descendants became Catholic. Meanwhile another noble family rose to fame: the Gouyon de La Moussaye. In 1629, Amaury III de La Moussaye married Henriette de La Tour d’Auvergne, the daughter of the Prince of Sedan and Turenne’s sister, and thus became Governor of Rennes as well as Lieutenant-general of Brittany.

Fief Churches survived as long as noble families remained Protestant. But many noble people returned to Catholicism under the reign of Louis XIII.

Among urban Churches, the one in Nantes was the most thriving because many Dutch tradesmen arrived in the most important port of the Kingdom. The community met for worship at the temple in Sucé on the banks of the Erdre river that the Protestants sailed up singing psalms.

The community in Rennes met at the temple in Cleusné which held the sad record of fires due to popular rage: four in the 17th century in 1613, 1654, 1661, and 1675. Each time the Royal power required their reconstruction at the city’s expense, despite the protests of the Catholics of Rennes. In 1675, the Protestant cemetery was desecrated. Most of the Protestants in Rennes were not natives of the city: they came from Vitré, but also from Normandy or Poitou.

The flight of the Protestants in 1685

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes all temples were destroyed. The region did not experience Dragonnades because the Governor of Brittany, the Duke of Chaulmes, refused to have troops come. Most Protestants recanted. Some fled to the Channel Islands, to England and to the Netherlands. The main ports of embarkation were Nantes and Saint-Malo. The Royal administration had the coast under surveillance, but with limited success in the region surrounded by the sea. In Vitré one third of the Protestants emigrated, and half of them to Nantes and Rennes. Those who were caught were imprisoned in Saint-Malo or Rennes.

The eclipse of the 18th century

In Nantes the Protestants soon acquired some semblance of freedom thanks to the foreign merchants from Switzeralnd and Germany, involved in the trade and manufacturing of Indienne, the sought after printed material in the 18th century. From 1740 secret worship took place at a Dutchman’s place, and then later in the Pelloutier manufacture of Indienne.

Breton Protestants were mostly in favour of the Revolution. But after the war was declared in 1792, foreigners became suspect and the Indienne manufacturing collapsed. The Protestant community of Nantes survived the revolutionary years but was weakened. It had no Pastor and no place for worship.

Brittany, a target for evangelisation in the 19th century

In the early 19th century Brittany had only one Church recognised by the Organic Articles of 1802: the one in Nantes that soared again after 1804. Some Protestants of Nantes reestablished their fortunes again like Thomas Dobrée, one of the major French ship-owners and Louis Say who constructed huge sugar mills.

The Protestant community thrived under the ministry of Pastor Benjamin Vaurigaud (1818-1883), a follower of Adolphe Monod. He created many works and wrote a History of the Reformed Churches in Brittany. At the end of the century the community comprised one thousand members and appealed to the newly converted, namely the very well-known Hippolyte Durand-Gasselin whose family presided over the community for half a century.

Thanks to the English migrants on the coasts of Brittany, a new Church was opened in Brest. In the beginning it was served by an English lay man, then in 1832 by a young French Pastor from the Revival movement, Achille Le Foudrey, who was given tenure with the help of the anticlerical city council. Around 1850, among the parishioners was the frigate captain Jean-Bernard Jauréguiberry, who was to be appointed Minister of the Navy in Waddington’s cabinet. He founded a new parish in Rennes and then in Lorient, with the help of the Evangelical Society.

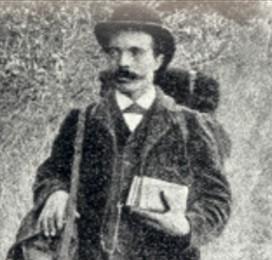

The French evangelisation was replaced by Welsh missionaries. The Revival movement reached Wales in the 18th century and prompted a renewal of the Celtic language and literature. So the Welsh became interested in their Celtic brothers: the Britons. The first Welsh missionary the Baptist Pastor John Jenkins, arrived in 1834, learned the Briton language and translated the New Testament with the help of a Briton writer. He created travelling schools that initiated new communities, notably in Trémel in the Côtes d’Armor département, thanks to a woman, Marie Ricou, and her son, Pastor Guillaume Le Coat.

The Baptist mission was strengthened by a Methodist mission and was supported by Welsh Churches. Pastor William Jenkyn-Jones exerted a considerable influence. He founded churches near Quimper and then in the harbours in the Sud Finistère where evangelisation was combined with anti-alcohol campaigns. In 1914 there were ten places of worship in Finistère-sud and several in the north.

The evangelicals largely contributed to the development of the Breton language, thanks to the translation of the Bible and hymns in the Breton language circulated by peddlers. The hymns on Welsh melodies or traditional Breton tunes were very much appreciated. Peddling was financed by several evangelical societies.

Moreover, the Popular Evangelical Mission was at work in Lorient and Nantes among the workers and founded ‘fraternities’. The Nantes Fraternity greatly developed and mixed spiritual activities with social action.

The birth of Protestant gipsy Churches in the 20th century

The Evangelical Mission pursued its action at the beginning of the century, developed in Paimpol but lost its impetus after 1930.

Many places of worship were destroyed in WWII in Brest, Lorient, Nantes, and Saint-Nazaire. After the war, worship took place in wooden sheds before temples were rebuilt.

After the war Pentecostals took over from the Mission and over twenty churches were opened in all major cities in the 1950s.

It was also in Brittany that the mission of the Pentecostal Pastor Le Cossec for the Gypsies was initiated in 1951. A few years later thousands of Evangelical Gypsies gathered near Rennes. The Evangelical Gypsy Mission spread all over France and abroad.

Today, Protestantism definitely is in the minority in Brittany but is also very diverse. There are about fifty places of worship, ten of which for the Reformed Church and the Popular Mission (Mission Populaire Evangélique de France), apart from the temples opened only in holiday resorts in the Summer.