From Guillaume Farel the Reformer in the Dauphiné region to the first four wars of religion (1522-1573)

To understand the early days and the progress of the Protestant Reformation in the Dauphiné region one should first follow the spreading of Luther’s ideas in cities thanks to printing. In Grenoble, capital of the Dauphiné region, some monks preached his ideas as early as 1523.

It also means following Guillaume Farel the Reformer (1489-1565) and a great friend of Calvin in his native province. In 1522 he converted Noble Ennemond de Coct. In 1532 he played a significant part at the synod of Chamforan where the Waldenses, disciples of Pierre Valdo of the 13th century, rallied to the Reformation. In 1561 Farel visited Churches in Grenoble and Gap taking along a pastor and a regent or school teacher, and then presided over the synod in Montélimar.

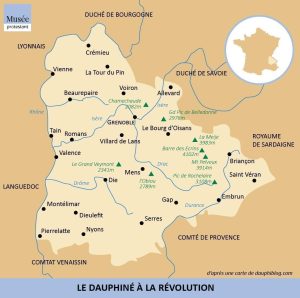

In cities the Reformation affected all social classes, monks, legal professionals, craftsmen and merchants, and nobles, those who could read. Later on, the movement spread into the mountains. In 1561 about forty Churches were planted and built following the Geneva model – 10% to 20 % of the population was converted to the ideas of Jean Calvin, the French Reformer and refugee in Geneva.

Violence in the Dauphiné region started in April 1562. La Motte-Gondrin, the king’s lieutenant, was massacred and hanged by the ‘Huguenots’ led by the baron des Adrets in Valence on 25 April 1562. The latter spread fear between the Rhone valley, Grenoble and Grande Chartreuse, from April to June 1562. Moreover three waves of iconoclasm hit the Dauphiné region in 1560, 1562, 1567, notably in about ten cities of the province, but also in country churches, as in Haut-Oisans. Violence divided the Protestant party. Grenoble was a Huguenot city for a few months after April 1563 ; in the south-east suburb called Three Cloisters, the first temple was established. Gap also experienced three periods of Huguenot domination.

At the time of the Saint Bartholomew massacre in late August and September 1572, the Dauphiné region was protected from violence – the king’s lieutenant, baron Simiane of Gordes implemented the Edict of Saint Germain, with the agreement of the parliament, but not on the king’s order. Still, a first wave of exile and conversion to Catholicism was significant in Grenoble as well as in the Oisans region. The Dauphiné region provided many representatives to the Union of the Provinces in 1573, as did all of the Languedoc region.

The era of Lesdiguières (1575-1622)

François de Bonne, Duke of Lesdiguières, was born at Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur. In 1575 he succeeded Charles Dupuy de Montbrun, the warlord. During the wars of religion he was nicknamed ‘the fox of the Alps’ because he was trained in small mobile and quick mountain ambush technics. From the Haut-Dauphiné region, a Huguenot stronghold , after several attempts he finally conquered Grenoble on 22 December 1590.

Faithful to the King, he became one of his commissioners and implemented the Edict of Nantes – what he wanted was ‘disarmament of consciences’ and obedience to the King. He continued waging war against the Savoie region. His Protestantism was weakening, so while helping the Reformed cause , by paying school teachers and pastors, from his castle in Vizille and Montélimar, he also supported the Catholics and their Counter-Reformation. In 1621 he took part in the siege of Montauban against the Protestants with King Louis XIII. On 24 July 1622 in Grenoble Lesdiguières converted to Catholicism and was granted many royal favours, for instance being appointed the last constable in France. He died in Valence on 8 September 1626.

The Protestants under the Edict of Nantes (1599-1679)

The Protestants in the Dauphiné region remained true to the king and did not take part in the 1621-1625 riots. The Dauphiné under the Edict of Nantes had a number of Huguenot clusters. There were 90 churches, 270 annexes and 73,000 Protestants, of which 40,000 in the Drôme valley, 12,000 in Trièves, 10,000 in the Hautes-Alpes, 11,000 in Vaucluson or 10% in the Dauphinois and 8% Huguenots in the kingdom. The province had 12 strongholds until 1629, but Huguenots in Dauphiné remained true to the king. The Chamber of the Edict in Grenoble was a major local originality. Until 1679 it judged the Protestants in the whole eastern part of the kingdom, with about 300 judicial acts per year.

The system called ‘Presyterian-synodal’ was set up with a consistory in each church, with pastors and secular people, the ‘Elders’. Each church had a school so that the children could read the Bible and sing hymns. Each consistory sent one elder and one pastor to the provincial synod, which, in its turn, sent representatives to the national synod.

Mens in Trièves, with its 1,000 faithful, was called the ‘small Geneva of the Alps’. Die with 4,000 faithful an academy and Protestant papers, was an important Protestant place as well. Gap also had a strong Huguenot minority. The financial and religious fervor seemed to diminish throughout the 17th century.

Towards the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes and exile (1679-1685) (1679-1685)

After 1679, the Edict of Nantes was applied ‘with rigour’. Conflicts were recurrent, as the Protestants were expelled from the consulats, the chamber of the Edict was eliminated, conversions highly encouraged. About fifty temples were destroyed between 1681 and 1685. During the Summer of 1683, the Reformed of Châteaurouble, of Crest and of Bourdeaux rallied to the ‘Camp of the Lord’ in the mountain between Saou and Bourdeaux. The repression was terrible: there were 200 victims.

The dragoons intervened after 1681. The conversions increased. Two bishops stood out and encouraged the dragoons to convert all the communities, firstly Daniel de Cosnac, bishop of Die and of Valence; secondly Étienne Le Camus, called ‘bishop of the mountains’ in Grenoble, who turned out to be less coercive in terms of conversion and managed to have the dragoons leave.

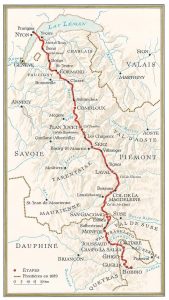

In 1685 upon the Revocation, temples were destroyed except for the one in Poët-Laval, set up in a common house. It is, nowadays, the Museum of Protestantism in Dauphiné. Ten to twelve hundred thousand Protestants took the road of exile to the Swiss cantons, to the German Principalities — Bade, Wurtemberg, Hesse-Cassel and Brandebourg with Berlin —, to The United Provinces, but also to Virginia or South Africa. Protestant communities of the Oisans region, for instance, totally disappeared. Today the association « Sur les pas des Huguenots »”(‘In the footsteps of the Huguenots’) perpetuates the tradition of the memorable paths from Poët-Laval to Germany, following the GR 968 hiking trail.

The time of female prophets and of the Desert (1685-1788)

Abjuration was massive but some officially ‘newly converted’ still remained truthful to the Reformed faith. Repression in all its forms increased.

In 1688, young women in the Dauphiné, including Isabeau Vincent, prophetised, spoke mystical words at night, urged the faithful to repent and to ‘leave Babylon’. Around 1700, pastor Amaud counted several hundred young female prophets. The « école des prophètes » (‘school of prophets’) was often frowned upon by the pastors of the Refuge.

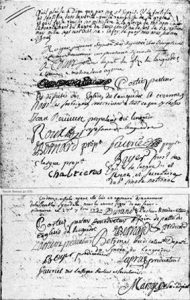

Clandestine assemblies of ‘the Desert’ multiplied, first at night in six places near Mens, for instance. Baptisms and marriages were celebrated by touring ‘preachers’, then by pastors from Lausanne, or from Switzerland in the Vaud region. There was a number of schools with clandestine regents. Repression remained serious, even in quieter times. Assemblies were sneaked up on, women imprisoned, as in the Crest tower, men sent to the galleys – 247 galley slaves out of 1,500 Huguenot convicts were from Dauphiné – and preachers were hanged. The first two pastors to be executed were Louis Ranc in Die and Jacques Roger, the restorer of Protestantism in Dauphiné. Jean Bérenger pastor of the Desert, called Dove, was killed twice in absentia and in effigy in 1759 and 1766. He performed 200 baptisms and about 700 marriages in the Desert, mostly in Trièves. Daytime assemblies in the Desert were tolerated after the 1760s ended.

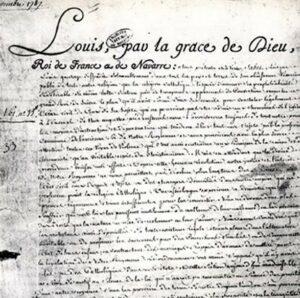

In 1787, the Edict of tolerance allowed Huguenots in Dauphiné to be entered in the civil register. There were only 43,000 left in Dauphiné.

The revival of Reformed Churches in Dauphiné under the French Revolution and the Empire

In Dauphiné, the Protestants were initially in favour of the Revolution. Antoine Barnave, a Protestant and mayor of Grenoble, had become the President of the constituent Assembly in mid-1790. He was against equality with ‘niggers’ and drifted from the Jacobins, and then got closer to the queen after the king had fled to Varennes. In 1792, he was accused, imprisoned, judged in 1793, and guillotined.

Under the Consular and the Empire, the Concordat and then the Organic Articles enabled to reconstitute seven consistorial Churches in Dauphiné, namely Mens, Orpierre, Crest, Die, Bourg-les-Valence, Dieulefit and La Motte-Chalancon. Temples were then built. According to Chaptal’s census, the Protestants were 1% of the population in Isère, of which 2% in Grenoble and 50% east of Trièves in Mens, Saint-Jean-d’Hérans, Saint-Baudille-et-Pipet. In the 19th century, the Drôme was the fourth most Protestant region in France. Hautes-Alpes had two Reformed pastors, Isère had four and Drôme twenty-six.

From the Revival of the 1820s to the Revival in the Drôme valley in the 1920s

Around 1820, Félix Neff, a Swiss Evangelist, called the ‘apostle of the Alps’, breathed a new religious spirit as a non-official pastor, an evangelist, a school-teacher and an agronomist at the same time. His success was proven by the increasing number of schools, two of them being models, in Dourmillousse and Mens. Pastor Blanc was inspired by his work and created the model Protestant school of Mens in1834, which survived until 1914. One thousand school-teachers were trained there.

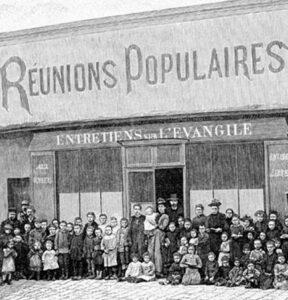

Religious fervour, however, decreased, mostly among men. Debates between orthodoxy and liberalism contributed to emptying temples. Part of the faithful turned to the Darbyist and Methodist minorities. Others turned to Free-thinking and free-masonry. Pastor Tommy Fallot, an emblem of social Christianity, contributed to revitalizing parishes in the Drôme valley.

After WW I, young pastors Henri Eberhard, Bordigoni, Jean Cadier, Édouard Champendal, Pierre Carron and Henri Bonifas initiated the Revival in the 1920s in the upper Drôme valley. The pastors united more easily in the new Reformed Church in 1938.

From WW II to nowadays

Under the Occupation, the parish in Grenoble increased its activities to help refugees, thanks to pastors Charles Cook and Charles Westphal, their wives and the parish ‘ladies’. Grenoble saw its parish grow by one third, comprising of many Jews, which was called the ‘Grenoble experiment’. The boarding-house ‘Snow Breeze’ at La Tronche, with Mrs Péan-Pagès, hid about a hundred young Jewish girls. Suzanne Casalis was linked to the parish, and developed a rescue operation for the Jews, between Grenoble and Mens, with pastor Pierre Gothié.

In Dieulefit, half-Reformed, a real small capital of Protestantism developed thanks to refugees of the elite. The Beauvallon school developed a new system of education inspired by Switzerland, and was headed by Marguerite Soubeyran, and became a haven for Jews and resistants. Dieulefit was a privileged place, like Chambon-sur-Lignon, with a refuge diffused in the local population, i.e. pastors and priests, complicit constables and town-hall secretary, who serially systematically produced fake papers.

Confronted by the FTP (Francs-tireurs and partisans) maquis in Vercors – communist oriented -, the Protestant population was divided. Some young men were tempted by the adventure.

Some theological students from Montpellier took refuge in the summer of 1943 in a camp called «theologians» in Tréminis, south of Isère. They suffered the wrath of treason and then German violence on October 19, 1943. The treasurer of the parish of Grenoble André Girard-Clot, the young René Lescoute and Bernard Laroche died in deportation. To our knowledge, it is the only maquis that can be judged Protestant in France.

After the war, Protestantism developed in urban and suburban parishes in Valence, Vienne or Grenoble.

The Grenoble urban district, for instance, developed along a new Protestant sociology: a middle-class with executives or intellectuals, often holding left wing or ecological views. Of the 500 French Reformed parishes, the one in Grenoble, considering their Sunday attendance to worship on the rue Hébert, ranked 50 in the 1960s. It grouped 2,000 parishioners in 1953, 3,300 in 1958, and 4,500 in 1968. The Protestant strongholds in Haut-Diois or in Trièves lost their demographic weight, even if the holiday population still shows a deep commitment to their ancestral Huguenot roots.

The debates on Communism and Christianity, the war in Algiers, the Winter Olympic games in Grenoble in 1968 and the 1968 events, caused heat and turmoil, along with a reflexion on involvement in a secularised urban society. In June 1961, Protestant women opened the first centre for ‘family planning’ in France. In 1968, ecumenism experienced since 1945, saw the construction of the ‘Saint-Marc ecumenical centre’ in Grenoble. Nowadays 1,120 families are registered in the united Protestant Church in Grenoble. A new protestantism ‘evangelical’, urban and of migrant origin Protestantism is growing.