Reception of the Reformation in Normandy in the 16th century

Normandy accepted the Reformation very early and with great ardour.

Alençon was the first city won over to Luther’s ideas by the influence of Francis I’s sister Marguerite d’Angoulême, who was first married to the Duke of Alençon (and later to Henri d’Albret who made her Queen of Navarre). From 1529 Luther’s Small Catechism was printed there by Simon Dubois.

What was considered the first public event to make Luther’s thoughts public took place in Rouen, in the Palace Hall: ‘the libel case’; libels were considered ‘heretic and blasphemous against the Holy Sacrament.’

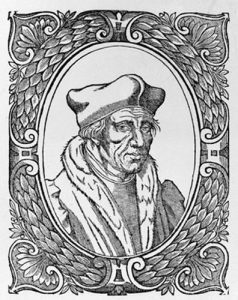

In 1533 Luther’s theses were displayed in Caen in the famous university, imbued with humanistic ideas taught by leaders of the cenacle of Meaux, among which Lefèvre d’Étaples and Briçonnet were the best known.

Many Calvinist Churches were built (1555-1557)

In Normandy, the Reformation was adhered to in cities as well as in the countryside.

In Basse Normandie, the rural world was greatly marked, whereas in Haute Normandie the Reformation was a city concern.

Protestantism spread very rapidly in Rouen. 15 to 20% of the population was converted, and Rouen had its first Church in 1546. In 1577 a Pastor called La Jonchée came from Geneva. In 1561 the Church comprised four Pastors and 10,000 members.

In 1559, in Elbeuf a quarter of the population was Reformed.

Between 1560 and 1568, Caen was mainly Protestant.

In 1557, Dieppe, like Rouen, had its Church with up to 14,000 members.

In Condé-sur-Noireau, most of the population converted to Protestantism.

Large numbers of Protestants could also be found in Le Havre, Lisieux, Pont-Audemer, and Pont-l’Evêque.

Apart from the academic world, representatives of the liberal arts were most sensitive to the ‘new ideas’. For example Jean Goujon (1510-1566), many magistrates (Rouen’s Parliament was involved), tradesmen and noblemen who brought the peasants along. Among the converted were also many men of the Church.

Protestant families were mostly present in cloth manufacturing, in book production (printing and editing), and in maritime professions.

The Protestants were prominent in maritime trade and some took part in the conquest of the New World, notably the Duquesne family from Dieppe (Abraham Duquesne went to Canada) or Jean Ribaut, also from Dieppe, who reached Florida.

The wars of religion

In 1562, the first war of religion affected Normandy: the Protestants were powerful and controlled in all the major cities, namely Dieppe, Rouen, le Havre, Caen, Falaise, Bayeux, Vire, and Coutances. The Count of Montgomery, leader of the Norman Protestants, stood up to the onslaught of the Royal Army led by François de Guise.

Dieppe and Le Havre fell into the hands of the English and were later retaken from the English by united Catholic and Protestant troops.

In 1570 the Edict of Saint-Germain limited worshipping to the possessions of the highest noblemen was implemented and consequently put the followers under the protection of a few families, namely the Montgomery in Ducey and Pontorson, the Sainte-Marie-d’Agneaux around Saint-Lo, or the Richier in Cerisy.

In Rouen, as in many provincial cities, a bloody response to the Saint Barthélémy (17-20 September 1572) claimed 400 lives.

It resulted in much recanting and, for many, in choosing exile. In the beginning people left for other regions in France, especially the Béarn, but some fled to the Netherlands, especially Rotterdam, or to England and even as far as Canada.

In 1574 the war started again in Normandy. Montgomery was beheaded in Paris in the Grève square. In 1576 the ‘peace of Monsieur’ restored peace.

During the Ligue wars (1589-90), Normandy was involved again. Mention can be made of the battle of Arques (1589) where Henri IV defeated the Duke of Mayenne, and that of Ivry during which Sully was wounded.

In 1590, almost all ‘leaguer’ cities, except Dieppe and Caen, were progressively won back by Henri IV, but Rouen still resisted.

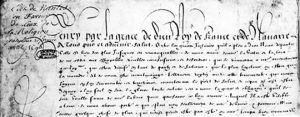

In 1598 the Edict of Nantes was ratified by the Parliament in Rouen on 23 September 1599.

Henri IV recanted and many Norman noblemen did the same. There were still almost a hundred thousand Protestants left in Normandy in the late 16th century, and the Churches led normal lives. After the Edict of Nantes, Protestant Normandy constituted a ‘synodal province’ comprising 58 Churches.

17th century

Strongholds were abolished in Normandy as in other French provinces in 1629 (the Alès peace).

National synods managed to meet in La Rochelle in 1607, and in Saint-Maixent in 1609. The last Provincial synod took place in Rouen in 1682.

The Caen Academy founded in 1652 still comprised one third of Protestants. It was active until the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. But limitations were imposed on Protestant education after 1660. In a number of instances clandestine teaching was resorted to. In 1669 limitations were even harsher: most schools, colleges and academies were closed.

Some temples were destroyed: in June 1685, the Parliament in Rouen commanded to have all the temples in the region brought down.

Children were abducted and forced conversions lasted until the reign of Louis XVI.

Marillac, the intendant of Rouen, was called ‘the great converter of Normandy’. He led the ‘dragonnades’ that took place in Normandy only in October 1685.

The exile of Norman families mostly occured after the Revocation, notably in Rouen where 405 heads of families, who owned buildings, migrated in 1686.

The region became poorer because of the massive exile of Protestant families. Some activities, such as the cloth industry or printing were severely affected.

18th century

The 18th century was the time of the Desert in Normandy as in all other French regions. The Protestants had to practice their religion clandestinely. Four Churches apparently kept their discipline and organization after the Revocation in Condé-sur-Noireau, Fresne, Sainte-Honorine, and Athis.

Worship was mostly a family practice.

Secret assemblies were also set up at the risk of being discovered, and their attendants either sent to the galleys or tortured: 300 prisoners, 37 to the galleys, and 18 sentenced to be hanged and drawn.

As in the Cévennes region, there were lay preachers such as the famous Claude Brousson, who had previously found refuge in Switzerland where he was trained in theology.

Under the reign of Louis XV, some constraints were eased.

The ties with England and the other Protestant countries fostered trade in general.

After the 1787 Edict of Tolerance, Protestant communities restructured themselves, especially in Le Havre, Bolbec, Luneray and in Rouen.

In Caen the Protestant middle class regained control of the main trading companies.

The Protestants readily agreed with the Directoire policies.

Towards the end of the century a few Pastors returned but were rarely attached to a single place.

In Normandy, as elsewhere, worship was reinstated after the Revolution. Cities were granted regular worship but a Pastor only in 1795.

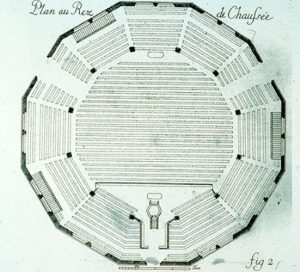

After the Concordat in 1801, the temple Saint-Eloi was built in Rouen to replace that of Quevilly.

19th century

In the 19th century the Protestants still living in Normandy, gathered in cities or scattered in the countryside. They played an important part in the social and economic development of the region. There were about 10,000 Protestants in the Seine-Martime département, but only 5,000 in the Orne and Calvados départements.

François Guizot (1787-1874) died at Val Richer in the Calvados département after an outstanding career as an historian and a politician under the July Monarchy.

Many Protestants arrived from Alsace after the 1870 war, namely Jules Siegfried (1837-1922), and they settled down mainly in Le Havre.

In the 19th century in Normandy the Revival movement found fertile ground. Methodists from England were quite active too. Tensions between liberal Protestantism and orthodox Protestantism developed.

The orthodox trend reasserted itself, thanks to Pastors, David Maurel (1818-1839), Guillaume de Félice (1828-1839), and in Dieppe Pastor Jean Réville (1826-1860).

20th century

In the 20th century Protestantism was still very much alive mainly in Rouen and Le Havre, but less so in Caen.

The most noteworthy rural Church (25% of the population) was in Luneray, where the temple was built in the 19th century.