16th century

The Evangelical propaganda was rapidly circulated in the Aunis, Saintonge and Poitou regions.

‘Preacher-Monks’ were first to spread the ‘Lutheran-heresy’, and preached the need to reform the Church but also to revert to the evangelical ideal. Philibert Hamelin was one of them, was forced into exile and fled to Geneva where he was a printer. In 1554 he went back to Charente as a Pastor.

In 1534 Calvin’s stay in Poitiers contributed to turning the regions into specifically Calvinist areas, which first circulated in cities such as Poitiers, a university city, and La Rochelle.

In Poitiers the new faith firstly concerned the law school circle where Calvin’s audience was most marked. Then it spread to craftsmen and tradesmen.

As everywhere else, Calvinism was implanted when education became fundamental and schools were developed.

The Reformed community in Poitiers, as well as in Meaux and Angers were organised and from their informal meetings an embryonic church emerged.

Indeed, between 1540 and 1550, communities formed. Many French went to Geneva to demand ministers and organisation models.

After 1550 the first churches appeared in Poitiers as well as in the Charente region, with pastors as early as 1559. Rules and regulations were drawn up in Poitiers in 1557.

(In 1558 the Parisian Pastor Antoine de Chandieu visited in Poitiers.)

But Francis I was worried and requested sanctions, up to imprisonment for those who preached Luther’s ideas, and even the death sentence. Philibert Hamelin was executed on 12 April, 1557.

From Poitiers the Reformation spread throughout the region, as early as 1538. Churches were ‘erected’ in Niort, la Mothe-Saint-Héraye, Parthenay, and Bressuire, 14 Churches altogether attended the colloquium of Bas-Poitou.

The rise of Protestantism after the first National synod

On 25 May, 1559, representatives of the Reformed communities in the Kingdom met at a synod in Paris and established a unified doctrine as well as an ecclesiastical organisation. The Churches of Poitiers and Saintes were represented.

The first Confession of faith was drawn up and the ecclesiastical discipline adopted on the basis of the churches’ autonomy.

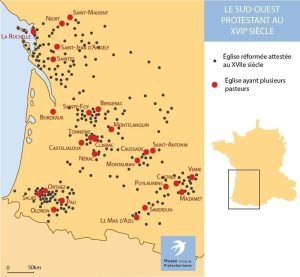

In the Aunis and Saintonge regions, as in Poitou, the Reformed faith spread very fast. Three years after the first synod in Paris, some fifty Churches were registered, served by 38 Pastors. In 1576, almost three quarters of the population had converted to Protestantism.

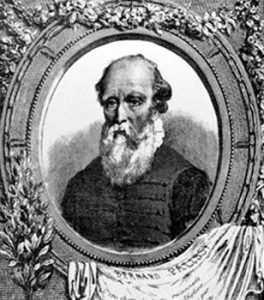

The city of Saintes had a large Protestant community, in which the best known representative was Bernard Palissy, who settled there in 1546 and devoted his work to ceramics.

In 1562, the city organised a Provincial synod.

La Rochelle was the city in the region that no doubt adopted the Reformation most readily. In the second half of the 16th century the greater part of the population was won over to the new ideas.

In 1571, the seventh synod presided over by Théodore de Bèze took place there, during which the ‘Confession of faith of the Reformed Churches in the Kingdom of France’ drawn up in Paris in 1559, was adopted. It is now known as the Confession of faith of La Rochelle.

It is significant that, in the list of National synods held in the 16th century, four of them gathered in Poitou-Charentes: in Poitiers in 1561, but also in La Rochelle in 1571, in 1581 and 1607.

Wars of religion

The region was not spared the civil wars that tore France apart from 1562 till the end of the century. Most of the fighting in the third war of religion took place there. The Huguenots won over cities in Poitou and Saintonge thus ensuring the safety of La Rochelle. But on 13 March 1569 they lost the Jarnac battle, during which the Prince de Condé was killed. They tried to besiege Poitiers but failed, and on 3 October, 1569 lost the battle of Moncontour in the north of the Haut-Poitou, though their military situation was not hopeless. Poitou, however, was devastated and the Protestant party lost a number of strongholds.

The Huguenots demanded cities to ensure their security. The Edict of Saint-Germain (1570) granted them four, among which La Rochelle.

The seventh war of religion ended with the Peace of Bergerac, confirmed by an Edict signed in Poitiers on 17 September, 1577.

During the eighth war of religion, Agrippa d’Aubigné (born in Saintonge, near Pons) was appointed Governor of the Isles and of the castle of Maillezaiz, which remained a stronghold until 1619. There he wrote part of les Tragiques.

In 1585 hostilities resumed in Poitou during the last war of religion. Mercoeur, the Governor of Brittany, almost reached Fontenay and the persecutions started.

Under Henri IV’s reign, however, the Reformed worship was restored in many places.

In the Poitiers region, there were 39 churches and 54 places of worship. Surprisingly the Reformed religion progressed during the wars of religion.

17th century

Throughout the quiet years between the Edict of Nantes and its Revocation, the Protestants were numerous and dynamic in the synodal province of Saintonge, Angoumois and Aunis. It comprised about 98,000 people. The population was highly diversified, all social classes were represented. It comprised numerous members of the nobility, men of law, doctors, craftsmen – especially printers and bookshop keepers- goldsmiths and clock makers – and a number of tradesmen.

In the 17th century Aunis and Saintonge were divided into four major colloquiums: the Aunis colloquium (La Rochelle), the Isles colloquium (La Tremblade, Oléron), the Saintes colloquium and that of Saint-Jean-d’Angély.

In Poitou there were about 90,000 Protestants grouped in three colloquiums:

The Bas-Poitou colloquium, presently Vendée; the colloquium of Haut-Poitou; and the colloquium of Moyen-Poitou, presently the Deux-Sèvres département.

Throughout the century the Protestant society evolved: under Louis XIII’s reign, members of the nobility diminished, and men of law significantly decreased.

In 1630 in some places, notably the Ile d’Oléron, worship was forbidden. Thus, Protestantism retreated.

In Poitou, the four colleges created in the 17th century, could not be maintained after 1685.

The case of La Rochelle was quite noteworthy: in the 17th century most of the population was Protestant. The cultural life was very active. The city housed several editors and a college where Greek and Hebrew were taught. Moreover the city had been independent since 1568, and its contacts with England worried the King who forbade the city to trade with England. Cardinal de Richelieu besieged the city to bring it back under the authority of the King.

The siege lasted from September 1627 to November 1628: 40,000 men surrounded the city and the King had the harbour access closed by a dyke, so the King of England could not send assistance.

The city eventually surrendered after a heroic defence leaving less than 6,000 survivors.

The Protestants and the New World

The Protestants played a noteworthy role in the conquest of the New World.

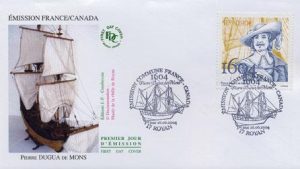

Pierre Dugua de Mons, born in Royan, notably founded the basis for a French colony in Canada called Acadie.

Henri IV appointed him ‘lieutenant-general of Acadie’.

When he returned he was appointed Governor of the city of Pons.

18th century

Persecutions increased after 1680 as in the rest of France.

From 1681, Intendent Marillac used the dragonnade method on the Protestants, which resulted in much recanting.

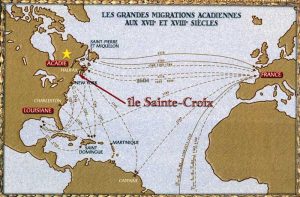

But a number of people from the Aunis, Angoumois, Saintonge or Poitou chose exile. For instance, some eighteen thousand people from Poitou took the path to Refuge. They often went by boat to La Rochelle, where they tried to board ships bound for the Netherlands, England or even America, though the Provost Marshall of La Rochelle made efforts to catch them before they could embark.

The New World was a Refuge land for many Saintonge inhabitants, where they founded the city called New Rochelle.

The period of the Desert

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, all temples were destroyed and Protestant worship forbidden.

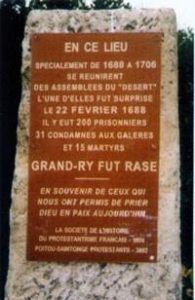

Persecutions however did not put an end to the Reformed Religion. It persisted, resisted and tried to recover in the days following the Revocation. The Protestants met clandestinely for assemblies where they read the Bible and sang psalms, though worshipping was forbidden and they faced risks.

The Grand Ry tragedy is sadly remembered: On 22 February 1688 the Dragons of Intendent Foucaut discovered an assembly and arrested some 200 prisoners, 30 of which were sent to the galleys and 3 were hanged.

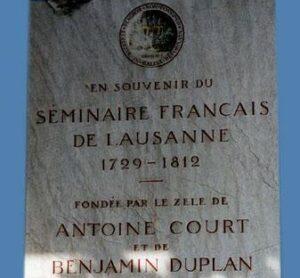

From 1726, the Lausanne Seminary trained preachers, who came to France and preached at their own risk.

One of them, Louis Gibert (1722-1773) from the Cévennes region, was trained at the Lausanne Seminary and granted a pastoral ministry in the Saintonge, Angoumois and Périgord regions by the Cévennes Synod. He founded ’houses of prayer’, notably one for regular worship in a barn in Breuillet, in September 1755.

So did Jean Jarousseau who was a Desert Pastor after he was consecrated at the Saintonge Synod in 1761.

People were condemned ‘for assembly reasons’ until the Revolution.

The Saintonge region lost about 100,000 inhabitants. In the Angoulême region, about 13,000 followers remained, mainly peasants.

19th century

The 1802 Organic Articles, issued from the Concordat, allowed the Protestants to reconstitute the Church and rebuild the temples.

The Revival movement, from Great-Britain and Switzerland, was very lively in that region, just as everywhere else in France. Strong links were established mainly with Geneva.

The Evangelical Society in Geneva was very active in Saintonge and Poitou, and promoted biblical societies and schools, notably for girls. Lucien des Mesnards (1809-1871) and Jean-Louis Benignus (1819-1894) were especially involved in the evangelising work.

Besides evangelising and educating, social work was largely developed and led by the Revival movement. Women played an important role.