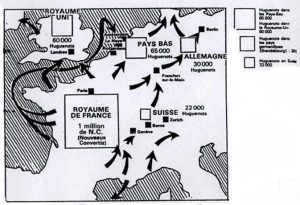

The Huguenot refugees

Nearby refuges of the French Protestants after the Revocation

Nearby refuges of the French Protestants after the Revocation

Jacques Saurin © SHPF

Jacques Saurin © SHPF

A large number of teachers, journalists, writers and “clerks” took refuge in the United Provinces. Intellectuals of the Refuge were first and foremost pastors. 680 pastors and professors of theology were thought to have left France; of which 460, (60%) reached the United Provinces.

Not all of them found positions : around thirty had to leave, a quarter had to accept an assistant position. Upon their arrival they tried to reinstate their working conditions, and used the only tools they had taken with them: the language and the books. The Huguenots played their most important role in book-selling and newspapers. On the whole they were the starting point of the “Huguenot international” which appeared everywhere in Europe, based on the printing in French of a literary, scientific and philosophical press.

Book selling

Pierre Jurieu

Pierre Jurieu

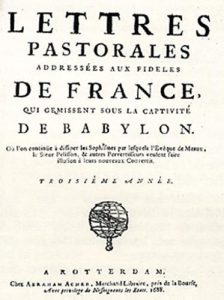

Pastoral letters from Pierre Jurieu (Rotterdam 1688) © SHPF

Pastoral letters from Pierre Jurieu (Rotterdam 1688) © SHPF

It has always played a major role. Among the 230 book-shops registered in Amsterdam between 1680 and 1725, 80 were owned by refugees. The proliferation of submitted manuscripts led to an increased production of printed matter in French. The majority of readers knew French, though they could not speak it well, but French was thus circulated, many of the books being translations of English or German authors.

Some of the books dealt with religious subjects. Pierre Jurieu (1637-1713) took refuge in Rotterdam as early as 1681 as soon as Louis XIV had the Academy in Sedan closed. He published the famous pastoral “Letters to our brothers who moan in captivity in Babylon” meant to sustain the spirits of the Protestants who had remained in France where the letters were covertly circulated.

Many newspapers and gazettes were created, which mostly presented reviews of recently published books, short works with the aim to popularise knowledge. Amsterdam had the oldest and most extended information network. Thanks to freedom of speech, possible censorship being exerted only in retrospect, the periodical press could develop fast. During the second half of the 17th century gazettes from Amsterdam, the Hague, Leiden were read throughout Europe. When the Refuge scattered the Huguenots all over Europe, the circulation area increased as readers discovered the most reliable information about the situation in France.

The literary field

Pierre Bayle, copy of the painting by Louis Ferdinand Elle

Pierre Bayle, copy of the painting by Louis Ferdinand Elle

Historical and critical dictionary, Pierre Bayle © Collection privée

Historical and critical dictionary, Pierre Bayle © Collection privée

In 1684 Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) published the first issue of the News of the Republic of Letters, the first literary paper enabling learned people to be acquainted with the latest publications. Its success was based on its independence, its impartiality and its non-partisanship. It was forbidden in France as early as 1685, but was smuggled in and even read at the Court. It was written in French and significantly contributed to spreading the French language. His dictionary which “was in itself a library to many people” was widely circulated, especially in England and in France. The two books were said “not to be about religion, but about science…and all scientists should be considered as brothers of this republic which is an extremely free State”.

In one entry of the dictionary an interrogated author said he was neither French, nor English, nor Spanish, but an inhabitant of the world in the service of truth alone. The success was also due to the people Bayle was surrounded with, such as Leibnitz, Fontenelle for mathematics, Denis Papin for physics, Leeuwenhoek for microscopy, Huygens for astronomy. His successor, Henri Basgne de Beauval, created the History of Scientists ‘Works. All this activity was highly profitable and spread European culture, mostly French culture.

Newspapers were created by Huguenots everywhere in Europe: the “Journal of Hamburg” by a pastor originally from Millau, the “New Journal of Scientists” by Chauvin, a pastor in Nîmes. They founded periodicals which presented the living thought of various nations: English library, then British, Italian library, German library.

The role of translators

It was crucial. Latin was inaccessible to a large number of readers. Neither German nor English were read by everybody. French alone could act an international intermediary. Therefore all the French refugees were to play a fundamental role in circulating the culture of the Enlightenment. A Huguenot from Brittany translated Spinoza. Jean Barbeyrac, the son and brother of pastors was born in Béziers, and after going through Switzerland, he became a law professor in Croninguen. He also translated works of the German Pludendorf who defended unwritten/common law. Translators sometimes took liberties with the original Latin text. Barberry’s hostility towards the supremacy of the French kings made him add a personal note in his own introduction (translated into English to increase its circulation) inscribed with the famous words “is the people made for the prince, or the prince for the people?” Mazel, a pastor from the Cévennes, translated the first work of the English philosopher Locke, and Pierre Costes from Uzès, a pastor to be, translated the English version of his famous Essay.

The English language was not well known on the continent and largely benefited from translations. English used the French language which everyone spoke, to spread the works and ideas published on the island.

All publishers and translators promoted the circulation of the French language, and all the intellectuals traumatised by the events of 1685 largely contributed to spreading the ideas, be they French, English or German, the rights of the people, tolerance, social rights. The Huguenot contributed to the move from the Mediterranean Catholic central axis to a Northern Protestant one.

The linguistic assimilation of refugees

French faded quickly, except among the elite. The Huguenots swiftly turned to English, German or Dutch. The French language deteriorated over generations, and was kept like a former title or identity. The French tongue survived thanks to liturgical usage and religious readings, as religious communities sometimes kept this tradition in their separate way of living.