Exodus

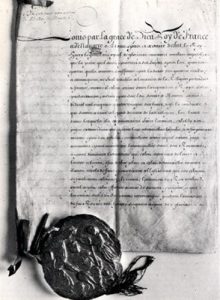

Since the Edict of Nantes was ‘rigorously’ implemented, as ordered by King Louis XIV, and as many and prohibitions were added from day to day, many Protestants decided to leave the country despite a Royal Edict of 1669, renewed in 1683, forbidding them to do so.

In 1685 the Edict of Fontainebleau or the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes prohibited exercising the Protestant religion, a massive Protestant exodus took place in spite of their being forbidden to ‘settle down in a foreign country’, which was extended to the ‘newly converted’ by a declaration in 1686.

Many departures despite the penalties incurred

In the Edict of Fontainebleau, ministers (pastors) had a differential treatment. If they did not recant hey had to leave the country within a fortnight.

Of the 700 pastors in 1685, 560 left for exile and 140 recanted.

For all other Protestants emigrating was strictly forbidden, and other measures were added:

- galleys for men,

- prison for women,

- confiscation of property for all.

The major exodus took place between 1686 and 1689. It slowed down significantly during the war of the League of Augsburg (1688-1697), but increased again after the Peace of Ryswick was signed in 1697.

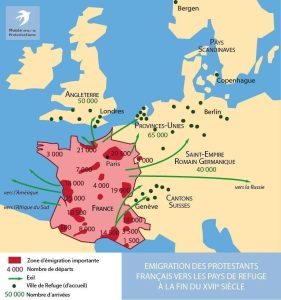

In spite of increased surveillance of the borders, the number of departures was considerable. There were up to 200,000 emigrants between 1685 and 1715.

In 1687, to try and stem the movement the death penalty was decided for the smugglers.

Host or Refuge countries

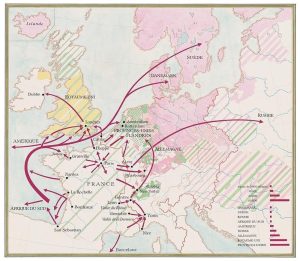

Emigration was organised according to geographical opportunities. Huguenots from the north and the west mainly went to England or to the United Netherlands. Those from the Dauphiné, Languedoc or Cévenness regions generally fled to Geneva. In the year 1687, up to 350 people fled to Geneva per day. Many of them went farther to the Swiss cantons, the United Netherlands or the many Protestant states in Germany, such as Brandenburg in Prussia – where were received very favourably.

The means of emigration

Leaving meant lengthy preparations. To make the passage easier there were smugglers, or otherwise certain ‘exit routes’ were available. On the way the emigrants found hosts who could accommodate them illegally in homes of co-religionists, in specific inns or in the embassies of Prussia or the Netherlands.

It was in these embassies that they could find help with the transfer of their funds.

Economic and cultural impact of emigration

The ones who left were often worked in industry, especially in textile trades, but they were also professionals, in the army, or in teaching. All those excluded from political office should not be forgotten either.

The high level of French living standards enabled the development of industry in host countries, especially in Germany ruined by the thirty-year war. The development of the French economy was stalled in some economic sectors, such as woodworking. Help had to be asked from German craftsmen, such as Oeben or Riesener.