The desire for ecumenism

Fathers of the Church © Wikimedia commons

Fathers of the Church © Wikimedia commons

There has always been a desire for ecumenism, from the very origins of Christianity. This is to do with the earth where we all live together. Even though there are a variety of different contexts and experiences, humanity is seen as being one. It is hoped that the earth will become inhabitable and provide a welcome to everyone in a universal dimension, which is the basis of Christian teaching and its eschatological hopes.

The Church Fathers and the first Christian communities, which were of various different origins, took this idea seriously. They set down to work by meeting together in ecumenical councils which put forward points of doctrine and organized the structure of the Church. They did not shy away from discussions which could have led to conflict, but instead they managed to establish points on which everyone could agree. When the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity a major step forward was taken towards unity. Since then there have been continual, positive debates within the universal (catholic) Church. However, it has not been possible to completely avoid schisms: the most significant ones being the Great Schism of 1054 and the Protestant Reformation in the XVIth century, set off by Luther’s excommunication.

Ecumenism since the beginning of the XXth century

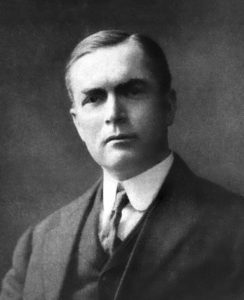

John Raleigh Mott (1865-1955) © Wikimedia commons

John Raleigh Mott (1865-1955) © Wikimedia commons

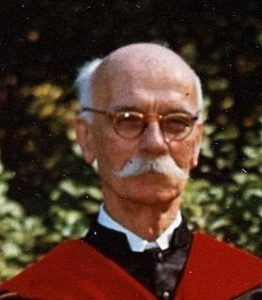

The pastor Marc Boegner © Collection privée

The pastor Marc Boegner © Collection privée

Willem Adolph Visser't Hooft (1900-1985) © Wikimedia commons

Willem Adolph Visser't Hooft (1900-1985) © Wikimedia commons

Abbot Paul Couturier (1881-1953)

Abbot Paul Couturier (1881-1953)

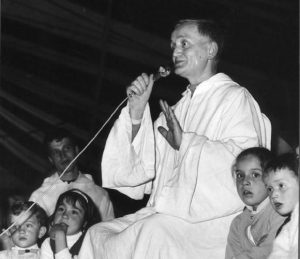

Brother Roger Schutz, prior of Taizé © Fédération Protestante de France

Brother Roger Schutz, prior of Taizé © Fédération Protestante de France

In the XXth century, Protestant missions needed to be organized in a more coherent and efficient way in order to carry out their activities properly. So for them ecumenism was important, on an inter-confessional basis. Little by little this spread to other branches of Christianity such as the Anglicans and the Orthodox Church, who played an active part in the establishing of the Universal Federation of Christian Student Associations (created in 1897). They also took part in some of the preparation of the Ecumenical Council of Churches (1948).

The Roman Catholic Church decided to remain voluntarily outside these discussions for a long time. This is because it considered that it was the only place where unity could be visible according to the authority of its Magisterium. However, after a somewhat difficult start, for example the encyclical Mortalium animos (1927), a more constructive approach was shown.

One can distinguish two dimensions of the ecumenical movement. On the one hand, there is a deep concern, inspired by the Gospel, to amend cases of disorder or injustice caused by certain forms of recent development. On the other hand, there is a more spiritual approach. These two dimensions often come together and provide each other with mutual support, which enables them both to move forward in a positive way to unity.