- The drive to war

After 1517 Protestantism developed in France. The number of Protestants grew rapidly; many noblemen converted and formed a powerful party. The Catholic majority felt rivalled.

In 1560 the Amboise conspiracy raised tensions. Some Protestants tried to abduct the young king, François II. They failed and were executed.

In 1561, Catherine di Medici, regent of France, gathered Catholic and Protestant theologians at the Poissy Conferences to attempt a reconciliation. To no avail. The rivalry led to war.

- The flood of hatred (1562-1572)

In March 1562, the troops of the Duke of Guise set fire to a barn in Wassy, causing the death of 50 Protestants. The civil war then spread all over France.

The conflict was on three grounds:

- religious: for the Catholics, Christianity can only be Roman Catholic;

- institutional: the throne of France rested on Catholicism, as God raises the king to his office;

- aristocratic: the rivalry was that of great families, the Guise on the Catholic side, and the Châtillon, led by Admiral de Coligny, on the Protestant side.

Violence increased and foreign armies were involved, namely German and English troops helped the Protestants.

The first three Wars of Religion succeeded one another, interspersed with ephemeral peace treaties.

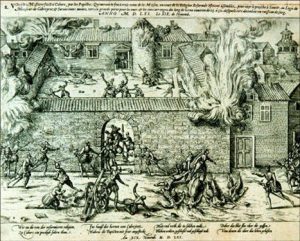

Hoping to bring the parties together, Catherine di Medici planned the marriage of her daughter, Marguerite de Valois, to the Protestant Henri de Navarre. On 24 August 1572 the Saint Bartholomew massacre took place during the celebrations. It was initiated by the Duke of Guise and King Charles IX approved. 4,000 Protestants were slaughtered in Paris, including Admiral de Coligny and other Protestant leaders, while more massacres continued in the provinces.

- A political war (1572-1584): complex issues

The Saint Bartholomew massacre had two major consequences:

– the Protestant population in the Kingdom decreased because of conversions and a massive exodus abroad;

– a fourth war broke out: the Protestants rose in the South and created the Union of Protestants, a sort of State within the State.

In 1574 the death of Charles IX made the situation even more complex: a political movement called the Malcontents, including moderate Catholics and Protestants contested the new King Henri III.

In spite of three more wars, neither of the two camps managed to win.

- Can the King of France be a Protestant? (1572-1584)

In 1584, the death of the Duke of Anjou, the King’s last brother – worried the Catholics. As King Henri III still had no offspring, the Valois dynasty had no heir. The leader of the House of Bourbon – King Henri de Navarre – thus became the legitimate heir, but he was a Protestant. That prospect was unacceptable for die-hard Catholics, who formed the ‘Sainte Ligue’ group.

Led by Duke Henri de Guise, the Ligue appointed another heir to the throne, namely the Cardinal of Bourbon, the uncle of Henri de Navarre. In this context the war resumed in 1585. Confronted by the powerful Guise, Henri III ordered to have Guise murdered in 1588. In response, the King was murdered six months later by a monk of the Ligue. Acknowledged as his rightful heir, Henri de Navarre became King Henri IV of France, and promised to receive a Catholic education.

- The ultimate phase of the wars (1589-1598)

Confronted with the fierce opposition of the Sainte Ligue, Henri IV had to conquer his realm. This long conquest lasted almost 10 years.

After being victorious at the Arques (1589) and Ivry (1590) battles, Henri IV besieged Paris.

But he realised he would never be accepted if he remained a Protestant. In 1593 he converted to Catholicism; and tradition has it that he said: ‘Paris is worth a Mass’. He was crowned King in Chartres on 27 February 1594.

On 13 April 1598 he signed the Edict of Nantes ending the Wars of Religion, after 36 years of civil war!

The Edict restored religious peace and granted the Protestants freedom of conscious, extended freedom of worship and access to all military or civilian jobs; the Catholics were granted the right to celebrate Mass everywhere.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, religious peace and tolerance were short-lived. Politico-religious conflicts flared up again under Louis XIII between 1620 and 1629. Louis XIV went further by reducing and suppressing religious liberties. It resulted in the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685.

It was not before the late 18th century that Protestants saw their religion acknowledged, and not before the second half of the 20th century that Protestants and Catholics opened up to each other in an ecumenical process.