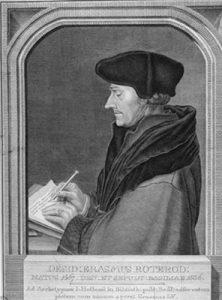

Erasmus and Luther

Erasmus (1467-1536) was a few years older than Luther (1483-1546). The former became a humanist by reading and by travelling a lot to Oxford, Paris and Bologna among other places. He had critical views on Catholic theologians: being trained in scholasticism did not entitle them to define good deeds – necessary to guarantee the salvation of the soul. That is why he became interested in Luther’s writings on the selling of indulgences, and was opposed as well to “soul trafficking”.

As for Luther, he read very attentively the scholarly edition of the New Testament Erasmus proposed in 1517. The translation of the Greek text into Latin the humanist also proposed seemed very right to him.

Despite their common views, Erasmus progressively retreated from the Lutheran circle of influence. The painter Albrecht Dürer wrote to him after Luther’s abduction, upon leaving the diet of Worms in 1521, asking him to speak to the civil and religious authorities so that he could be liberated, Erasmus did and said nothing.

Later on a controversy about how much liberty men were allowed opposed Erasmus to Luther.

A controversy about salvation through good deeds

In 1523, shortly before he died, Pope Adrian VI and a friend of Erasmus, asked him to confirm that his opinion on “salvation through good deeds” agreed with that of the Catholic Church. Erasmus wrote On Free Will in 1524, which was not even read by the commissioner, but by his successor Clement VII who was more hostile towards Luther than Adrian VI. Luther immediately answered in a strongly polemical text entitled On the bondage of the Will.

Erasmus’s opinion on salvation through good deeds was rather subtle: he considered that if good deeds opened the way to personal salvation, it all relied on the free will (freedom of choice) of the one who achieved them.

Luther considered that thanks to his willpower, as well meaning as that could be, man could certainly act, but that had nothing to do with his personal salvation (bondage); his belief alone in justification through God’s grace in Christ guaranteed this promise. The free commitment (the freedom of the christian) was then the context in which his action (and the ensuing deeds) was totally relevant.

The two opinions were closer than they seemed: for Erasmus the willpower cannot ignore piety and faith. He did not draw all the consequences because his concern was to remain within the Catholic Church, hoping to contribute to opening up the church.