Musical training

When Luther studied in Eisenach, he had music lessons along with dance and singing -so did Melanchthon and many of his contemporaries. He learned to distinguish between the different musical genres. Later on, living in a monastery where liturgy played an important role, he could refine his skills. Luther was able to transcribe folk melodies and to harmonise them, as well as to write melodies on psalms in everyday words. He met musicians, such as Ludwig Senfl attached to the Bavarian court and Johan Walter attached to the Saxon court. The latter introduced him in Rome to Josquin des Prez (1440-1521). When Frederick the Wise died, Johan Walter backed Luther, but his successor, John the Magnanimous did not share the same appreciation of music.

Reformation and music

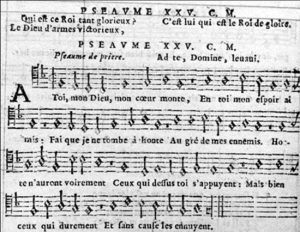

As Luther reformed the liturgy, he accorded full importance to the sermon and to community singing, see On the order of the divine service in the community in 1523. The singing called Choral singing was defined as an assertion of faith, and a spiritual commentary on biblical texts. It could be backed by an organ -chamber organs at the time-, or by an instrumental group.

To implement the change, worshippers had to be acquainted with music practice. Schools or parishes became responsible for vocal training, given by a “cantor”.

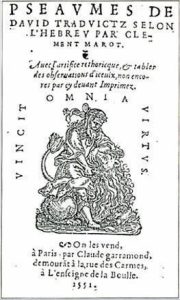

A hymn book also had to be designed and published. A team of musicians around Luther was in charge of the project that resulted in the geistliches Gesangbuchlein or small sacred song book. Luther himself composed thirty-six hymns on German texts, some based on psalms, others being spiritual commentaries, often adapted to folk melodies. But Luther did not discard the use of Latin, which he appreciated its facility in adapting it to music. Besides, some of his composer friends used both German and Latin.

Many of Luther’s hymns have survived, among which Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott (A mighty Fortress our God is still), or Christ lag in Todesbanden (Christ lay in death’s bondage).

They are still in use in their simple harmony, but the themes were taken up in great polyphonies, those by Johann-Sebastian Bach being the most impressive.

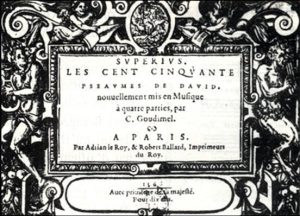

The hymns were translated and crossed borders. They were often sung in French reformed liturgies, added to psalms by Goudimel (ca 1520-1527) that Calvin had promoted. The French reformer may not have been as sensitive to music as Luther, he mistrusted choral singing as potentially distracting, as the main theme could lead to variations and involved instrumentation.

Luther's heritage: Heinrich Schütz, Dietrich Buxtehude and Johann-Sebastian Bach

The role Luther had granted to music and choral singing greatly helped the development of this art in German speaking countries. Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672), Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707), Johann-Sebastian Bach (1735-1782) often used Lutheran themes in their cantatas and oratorios. Each of them developed his own musical language and his instrumentation, but among them Johann-Sebastian Bach gave that language a creative power that had rarely been equalled. All were members of families with violinists, harpsichordists, cantors, teachers, or instrument makers.

The musical skills of Johann-Sebastian Bach’s family could be traced to Luther; in fact the first of them Hans Bach, the son of a baker, was born about 1550 and composed hymns. All his descendants down to Johann-Christian Bach (1735-1782) were devoted to music in some way or another as cantor, composer or organ-builder.