Luther's skills

Luther had studied at the University of Erfurt, where the humanities were a great influence. He gained a good knowledge of Hebrew, Greek and Latin, even if he was not as talented as Melanchthon and all those who were involved in his translation undertaking. He also had a very detailed, in depth knowledge of the German language, in its daily, political or diplomatic use:

“In my translation of the Bible I strove to use pure and intelligible German. Our quest for an expression could sometimes last four weeks without us being happy with our work. (…) In addition, I have not worked on my own: I recruited assistants from everywhere. I tried to speak in German, not Greek nor Latin. But to speak German one should not turn to texts in Latin. The house-wife, children playing, people in the street are those to learn from: listening to them teaches one how to speak and to translate – then they will understand you and know how to speak your language.” (Luther, An Open Letter on Translating)

Last but not least, Luther’s theological outlook (salvation through grace) produced wording rather different from that of the most common Latin translation, Saint Jerome’s Vulgate.

The main steps in the translating process

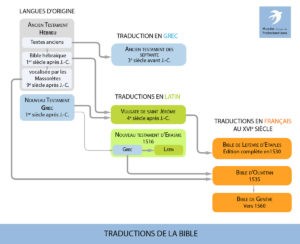

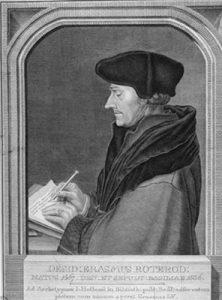

As early as 1517 Luther had already translated parts of the Bible, such as the penitential psalms, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Magnificat. Melanchthon was astounded by the quality of the translation and persuaded Luther to do a more systematic job. In 1521, while he was forced to stay in Wartburg, Luther translated the New Testament based on Erasmus’s second edition (1517) from the original Greek, and inspired by some of the choices made by this humanist in his translation to Latin.

In 1523, he translated the Pentateuch, and, in 1524, the Psalms based on the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek translation of it – the Septuagint.

Then, with a group of translators (Caspar Cruciger, 1504 -1548; Justus Jonas 1493 -1555; Mattaüs Aurogallus, 1490 -1543; who met weekly, he translated all the other books in the Old Testament, including those the Hebraic Canon had not kept because they were not written in Hebrew, but in Greek or Aramaic: the Deuterocanonical books. This great work was completed in 1534. The first edition was soon sold out. Many more followed in Luther’s lifetime, among which one was illustrated by Albrecht Dürer and another by Lucas Cranach the Elder. In 1546, 500,000 copies of the whole Bible, published in 93 cities, were in circulation. The average price was two florins.

The choices

Like any translator Luther faced a challenging task, always subject to criticism and improvement. To do the task he stayed as close as possible to the original texts in Hebrew and Greek, and his awareness of their poetry and musicality was striking.

Furthermore, there were inevitably problems with comprehension and interpretation and he clearly presented the assumptions, the angles from which he had to choose:

- In some specific cases, the reformer clearly took liberties with the text: for instance the shekel – currency of ancient Israel – became the Sibberling – the currency in Saxony at the time of Luther.

- Most differences with existing translations were based on theological choices – besides the original texts, he had read the Septuagint, the Vulgate, as well as various translations of the Vulgate into vernacular languages. He had read widely (the Septuagint, Vulgate, various translations into the vernacular, as well as the original texts) and most differences between translations rested on theological differences. For instance, he saw the Psalms as waiting for the coming of Christ, so ran the risk of misinterpretation.

In his An Open Letter on Translating (1530), Luther gave some valuable hints about his working method. Taking the Annunciation (Luke 1; 28) as an example, he reflects on the meaning of the angel’s greeting to Mary. The Vulgate offers: “Ave Maria, plena gratiae”: ”Hail Mary, full of grace”. In these terms, Mary could be considered as able to intercede with God, and this interpretation was strongly supported in the teachings of the Catholic Church. But, theologically, it doesn’t have to be this way. The Greek term corresponds to one in Hebrew, also found in Daniel, expressing a warm affectionate greeting. So Luther suggested the following translation: “Gegrüsset sei du, Holdselige”: “Hail Mary, fair (hold) and blessed (selige)”.

A number of other choices were significant: for example, God speaking to Moses in front of the Burning Bush “Ich werde sein, der ich werde sein”: “I shall become whom I shall become”. Dynamic overtones are given to account for the unaccomplished tense in Hebrew. Though Hebrew lends itself to this option, it is not always chosen. In French the most usual translation is “Je suis celui qui suis”: “I am who I am”.

Luther often made his choices clear in his sermons in which he explained his theology.

The spread of Luther's translations

Luther’s translation, thanks to the way language was used, was a great success and vital to the spread of the Reformation in German speaking countries. His work was a considerable influence on the development of the German language. The different dialects were unified in Hochdeutsch, High German, with its romanticism revealing its literary and poetical qualities.

Obviously the translation would not be without errors. Some were quickly corrected, especially those relating to the book of Job. Others became apparent with the advances in linguistics and Biblical exegesis. Although Luther’s translation has been extensively revised, the version in current use by German speakers has largely maintained the reformer’s theology.