Training

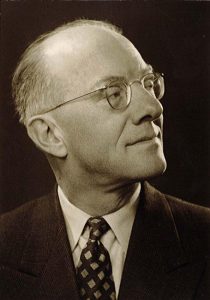

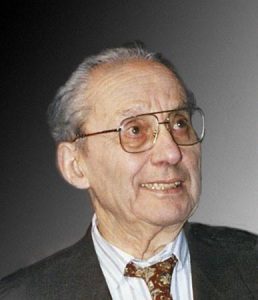

Oscar Cullmann was born in Strasbourg, then belonging to the German Empire, in 1902. He was the youngest of nine children in a Lutheran family, and his father was a schoolteacher. He studied at the Jean-Sturm Secondary School (Gymnasium), and then was admitted at the Protestant faculty of theology in Strasbourg, where he gained in-depth knowledge of Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic.

In 1925 he was admitted to the free Protestant faculty of theology in Paris as well as for the IVth section (Sciences and religions) at the École pratique des hautes études (EPHE) where he followed the classes of Maurice Goguel (1880-1955). Besides, he also attended classes of Alfred Loisy (1857-1940), elected to the Collège de France after the modernist crisis. Here he developed subjects were the basis of his book for which he was excommunicated by Pius X: The Gospel and the Church (1902); In 1916, it concerned the Epistle to the Galatians, and more generally about New Testament exegesis.

In 1926 Oscar Cullman was appointed director of the Saint-Guillaume college in Strasbourg where Protestant students of theology lived. In 1927 he was in charge of Greek classes at the faculty of theology. In 1930 he submitted his bachelor thesis on the links between gnosticism and Judo-Christianity.

Academic career

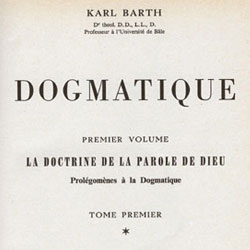

His bachelor degree enabled him to be appointed associate professor in Greek and New Testament at Strasbourg. His classes included the Gospels, Paul’s Epistles and the Acts of the Apostles. In 1938 he was seconded to the Protestant faculty of theology at Basel University where he taught the New Testament and the history of the first century Church, in German. He collaborated with Karl Barth (1886-1968). After the war he was often his interpreter in French, especially when visiting the French army of occupation in the Black Forest.

From 1945 to 1948, after the war, he kept his position in Basel but also resumed teaching in Strasbourg, once he had submitted his Doctorate thesis Time and history in first century Christianity (1945).

His work entitled Christ and Time (1946) on the history of salvation earned him international recognition.

In 1948 he was elected director of studies for the forth section at the EPHE in Paris. He succeeded to Maurice Goguel and became Professor of New Testament and Greek at the free Protestant faculty of theology in Paris (1945-1968).

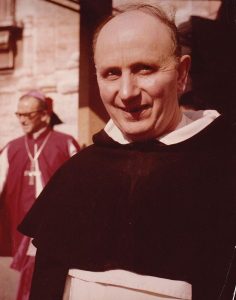

He was a long-time friend of the Dominican father Yves Congar (1904-1995), met Pope John XXIII and took part in the Vatican Council II (1962-1965) on his personal request.

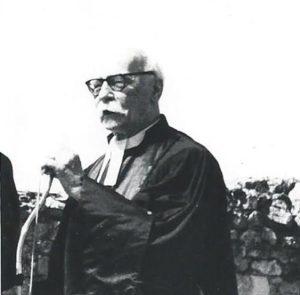

In 1972, he was elected at the Académie des sciences morales et politiques (Academy of moral and politics sciences) to take the seat of pastor Marc Boegner (1881-1970).

After 1972, he was retired but still very active. He took part in the creation and was head of the ecumenical Institute Tantur in Jerusalem that worked along with the Notre-Dame Catholic University in Illinois, U.S.A., on themes linked to the history of salvation. He also published a noteworthy work on prayer in the New Testament.

Oscar Cullmann, 96 years old, died in Chamonix in 1999.

Exegesis of the New Testament

Oscar Cullmann specialized in the exegesis of the New Testament and in the history of first century Christianity. According to him – and through his works on modernist exegesis (based on the problem of the Kingdom raised by Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930) in The Essence of the Gospel and by Loisy in The Gospel and the Church) – the New Testament could help Christians meet the challenges of the present. He insisted on Christianity being rooted in Judaism and was interested in the links with the Esseniens. About the history of salvation, according to him the final phase had already started, even though it could only be accomplished in times to come.

Oscar Cullman thus started a debate with the German theologian Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976) who considered the discourse of the New Testament partly mythical and needing to be translated into modern speech and related to the interrogations of 20th century people – cf. Jesus, mythology and demythologising, published in 1968 with a foreword of Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005).

Cullmann provided an alternative, i.e. the Bible should be interpreted, but the history of salvation cannot be considered ‘mythical’, except if a radically different faith was to be created; Jesus Christ was just as difficult to accept for the early Christians as for today’s man.

Besides academic works, Oscar Cullman published very clearly argued opuscules on practical and topical theology issues.

About baptism he recalled that the New Testament presented a number of occurrences when faith preceded baptism and also that faith was not required at the time of baptism. It was a discussion with Karl Barth (1886-1968) who, as he was writing Dogmatics, gradually moved away from a tradition favourable to baptising young children.

About the resurrection of the dead, Oscar Cullman quoted the preaching of the first Christians, and linked the notion of resurrection to themes in the Jewish apocalyptic, namely that contrary to the immortality of the soul, it implied a double discontinuity: the destruction of the being and its recreation through a renewed act of creation, understood as the resurrection of bodies.

About prayer, Oscar Cullman interpreted Our Father. Any prayer should be a meeting with God in unity with His will, which means we have to accept that the request may not be granted. Our prayers make us God’s assistants to repair the wounds of the world in which we are immersed.

Political and social involvement

Oscar Cullman based his involvement on the message he found in the New Testament. He was confronted to with an especially violent world with the two world wars that deeply impacted the civil society, and he was sensitive to injustice and concerned about practical actions.

In 1918 when Alsace and Lorraine were returned to France, Oscar Cullman exposed the excess of special courts against people accused of ‘disloyalty to the French Homeland’.

As early as 1934, after Hitler’s rise to power, he took sides with the German confessing Church against the Protestant Church of the Reich and was opposed to the Deutsche Christen – German Protestants who joined Nazism ‘German Christians’- and to their ‘tampering with the Gospel message’.

In 1945 he set up a fundraising in Basel for his colleagues at the University of Strasbourg, who were going back to Alsace after they had taken refuge in Clermont-Ferrand during WWII. He also raised funds in Switzerland for the University and for the Protestant Churches in Alsace and Lorraine.

After WWII, he lamented the silence of Churches on the crimes of Soviet Communism while they condemned the crimes of Nazism. He publicly defended his colleague Ernst Lohmeyer (1890-1946), a German theologian, falsely accused of war crimes on the Russian front, and eventually executed by the Soviets.

Involvement in an ecumenical dialogue with the Catholic Church

Oscar Cullman took part in the sessions of the Ecumenical Council of Churches. But he also developed exchanges with the Roman Catholic Church. Thanks to his contacts with the Modernist movement, through his lasting friendship with Yves Congar – a Dominican father made Cardinal in 1994 – he paid attention to the links between the Scriptures and tradition, but never opposed them. In 1948 he taught at the Waldensian faculty in Rome and attended the pontifical Biblical Institute directed by father Augustin Bea (1881-1968). During his stay, he was formally received by Pope Pius XII. His work on Peter, the apostle, was well received in Rome.

Oscar Cullman always approached the topic of ecumenism in light of the New Testament. In 1957, during the week of prayer for Christian Unity, he launched the idea of a concrete action recalling the fundraising in the community by Paul, the Apostle, in favour of the Jerusalem Church, i.e. a mutual collection between Protestant and Catholic parishes. The idea was approved and implemented in many places, but was discontinued because of the lack of support from the Ecumenical Council of Churches and the Secretariat for Christian Unity.

In 1962, father Bea, who had been appointed Cardinal in 1959 and was head of the Secretariat for Christian Unity, forwarded an invitation to attend the Vatican Council II (1962-1965) as a personal guest of the Pope, which gave him more leeway than to the representatives of other religions attending as observers. He attended every session and could take part in work sessions of the Secretariat for Christian Unity. Though he could not speak at the Council, he talked with Council Fathers during breaks and meals, and had interviews with Pope Paul VI.

Oscar Cullman stood for the idea of ecumenism not as a merger of Christian Churches but towards unity through diversity. Each would remain autonomous, but all would live in communion while respecting the others. The communion of Churches should enable common worship, and not exclude Eucharistic hospitality.

After 1972, he strengthened his contacts with the Orthodox and even visited Romania in 1975, and then Greece in 1978.

In 1980 he inaugurated the ecumenical garden at the Mount of Olives, where Christians are welcome to pray for unity.

After Oscar Cullmann by Matthieu Arnold