Captain, diplomat and councillor to the King of Navarre

Philippe de Mornay, Lord of Plessy-Marly, also called Duplessis-Mornay, dedicated his entire life to the Protestant cause.

He accompanied the King of Navarre, the future Henri IV, in his political and military struggle. He was an outstanding soldier and participated in decisive battles opposing the Huguenots to the armed forces of the League. He won fame at the battle of Coutras, on the 20th of October 1587.

Together with his military activities, Duplessis-Mornay exercised an important political role : as early as 1576, he was a councillor to the king of Navarre and ambassador.

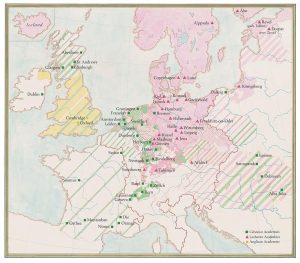

When on mission to the Prince of Orange (1578-1582) he measured the European dimensions of the Huguenot struggle. In the Low Countries as well as in the Kingdom of France, by respect of the liberty of thought, he became the protagonist of confessional co-existence as opposed to the Spanish hegemony. In 1582 he leaves the Low Countries within the hands of Monsieur, the King’s brother (François d’Anjou) and once more joins the King of Navarre.

Following the death of François d’Anjou in 1584, Henri of Navarre became the presumed heir to the throne. Duplessis-Mornay became more and more involved in national political debate and attempted to act in favour of a legitimate access of the King of Navarre to the throne of France.

The assassination of the Guise brothers by order of King Henri III opened up new era. De Mornay esteemed it was urgent that Henri III be reconciled with his legitimate heir. But the murder of Henri III by Jacques Clément in 1589 interrupted de Mornay’s attempts to reconcile the two parties.

Duplessis-Mornay and Henri IV

With the access to the throne of Henri IV in 1589, the task of de Mornay as councillor became extremely difficult. He was more and more frequently kept aside from royal initiatives taken against his advice. The King rallied the main Roman Catholic lords and promised to protect their religious stand. The pressure of the League and of Spain was such that the King announced his conversion to Roman Catholicism. De Mornay condemns this conversion but remained faithful to the King.

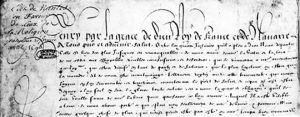

He took an active par in the negotiations concerning the Edict of Nantes. He did not take part in the wording of the Edict, but contributed to its establishment by pleading with the King in favour of the Protestants and calling for moderation. He did his utmost to overcome all difficulties.

He was regarded by the Protestants as their most obvious protector at the King’s councils, but his influence declined and he left the court in 1598. In 1600 he was definitively put aside from power, following what Hughes Daussy called « the Fontainebleau sacrifice » : his disastrous and humiliating confrontation concerning the Eucharist, with the bishop of Evreux, Jacques Du Perron whom the King openly supported.

From that time on his whole activity was concentrated upon Saumur to he was appointed governor in 1588 and where he founded the Academy of Protestant Theology in 1604.

He worked for the revival of Protestantism and founded the Academy of Protestant theology of Saumur in 1599.

The political thinker and writer

Duplessis-Mornay was not only a man of political action but likewise of political thought.

He was the inspiration of the propaganda writings that circulated throughout the entourage of Henri of Navarre during the period of 1585-1589. His aim was to prove that the Guise family compromised with the enemy, especially when, on the 31st of December 1584, they signed the treaty of Joinville with the representatives of the King of Spain.

In opposition to the League’s firm defence of the notion that faithfulness to the prince is conditioned by one’s religion, Duplessis-Mornay maintained that politics should be distinct from religion. He defends the Salic law against the law of catholicity upheld by the Guise family.

His works show that Duplessis-Mornay was not only a man of political thought and action, but likewise a theologian and exegete.

The all to unity constantly appeared throughout his activities and his thought. In politics he attempted to find a minimum consensus, while in religious affairs he tried to find and establish the principles common to all.

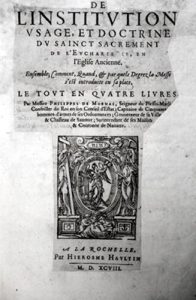

His attacks against the absolute power of the papacy in his Treatise on the Church (1578) and his Concerning the institution, the usage and the doctrine of the Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist in the early Church (1598) did not prevent him from working in favour of conciliation between Roman Catholics and Protestants, nor from upholding the idea of a religious concord and hoping for the gathering of a joint council of Protestants and Roman Catholics. He upheld the latter notion in his In favour of the Council (1600). He esteemed that between Calvinists and Catholics there were no divergences of a fundamental nature. For this reason nothing should oppose the co-existence of the two confessions.