A long-lasting prohibition

As from the end of the XVIth century, cotton fabrics printed in India (les indiennes) became extremely fashionable. They were imported by the Portuguese, and later by the Compagnie Française des Indes Orientales from its very foundation in 1664 by Colbert.

But pressure from cloth manufacturers in Normandy and silk manufacturers in Lyons succeeded as from 1686 in getting Louvois to prohibit both the importation of printed cotton from India and the printing on white cotton cloth throughout the realm.

The destruction of woodblocks used for printing on fabric was ordered by decree. As this prohibition came soon after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, numerous artisans – many of them Protestants from the Gard department – were forced into exile or into hiding. This turned out to be favourable to the establishing of cotton printing factories in Switzerland, especially in the canton of Neuchâtel. The most famous of these was close to the Bied river.

Despite such prohibitions, cotton fabrics were printed secretly, especially around Paris, where the indiennes were most fashionable. The Compagnie des Indes moreover, succeeded in getting a dispensation for shipping cotton fabrics. As from 1740, repressive measures were relaxed and in 1759 fabrics could once more be printed or painted.

Oberkampf in Jouy-en-Josas

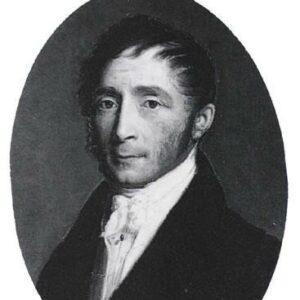

Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf (1738-1815) arrived in France at that time. A Protestant of German descent, he first worked with his father, in Aarau in Switzerland, then at the Koechlin-Dolfuss printing factory in Mulhouse, and finally with the Parisian engraver, Mr. Cottin.

He was associated with a Swiss, Antoine de Tavannes, and established a factory in Jouy-en-Josas, by the Bièvre River, whose water was renowned for colour fixing.

After initial difficulties of a financial nature, the business entered a period of strong growth.

The qualities of the indiennes de Jouy were appreciated at the court and Queen Marie-Antoinette visited the factory in 1781 and the factory was granted the name Manufacture Royale.

Building extensions were urgently needed. In 1792 Oberkampf had a sizeable workshop built : 110 metres long, 14 metres wide and 23 metres high. The production rate kept growing, while both the factory and the number of workers increased in size.

Faced by difficulties of getting white cotton from India, Oberkampf opened his own weaving factory in Essonnes in 1804.

Reasons for success

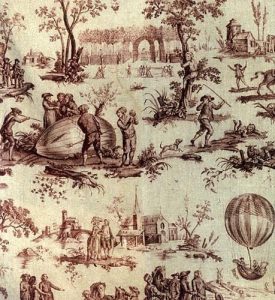

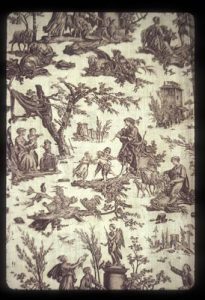

The success of the Manufacture de Jouy was the result of a good manufacturing organization and an appropriate framework for the purchase of raw materials and the sale of fabrics. Oberkampf always showed a great interest in improving manufacturing techniques, the quality of dyes and the variety of designs. The creation of the latter was very often entrusted to outstanding artists. All these factors helped to build the reputation of the Toiles de Jouy.

Oberkampf surrounded himself with various members of his family who helped him run his business : his brother Frédéric, his nephews the Widmers, his brothers-in-law the Petiteaus and later, his son-in-law Feray and his youngest son Émile.

The decline

However, as from 1808, recession threatened. The Napoleonic continental system of 1809 resulted in the stagnation of business, competitors got organized and fashion changed. The Allied invasion of 1815 caused the closing down of the workshops. Oberkampf died the same year.

His son Émile succeeded him until 1822, when Barbet, his associate, became sole manager. The Oberkampf dynasty was replaced by the Barbet dynasty known as Barbet “de Jouy”, to differentiate them from the other branch of the family, likewise manufacturers of indiennes, but in Rouen.

The Manufacture was finally closed down in 1843. The machinery was sold and most of the buildings were pulled down. Today only two wings of Oberkampf’s house still remain : one has become the town hall of Jouy-en-Josas, and the old weevils’ mill had another storey added before becoming a chemical factory in the early XXth century.