The origin of the army chaplaincy

The history of Protestant chaplaincy in the army began within the Roman Catholic Church, where protestant history usually does. King Saint Louis legalised the chaplains, but gave them no formal framework. In fact, he militarised the chaplains who accompanied lords going to the crusades.

There was then no national army. The lords, depending on their power, armed knights and lent troops to the king, mainly archers and infantry. The nobility accompanied the king.

Chaplains normally accompanied their lords to war. Until Philippe lV le Bel became king in 1302, the lords had the right to private warfare. Sometimes they fought for trivial reasons ; over a piece of land, over some customary right that had not been respected, a quarrel.

In 1531 Ulrich Zwingli, chaplain to the Zurich troops, was killed at the battle of Cappel. He was killed while helping the wounded and the dying. He was the first Protestant chaplain to be killed.

The chaplains' statute

The role of Protestant military chaplain was not acknowledged until the Crimean war in 1854. Pastor Roehrig went to Crimea with the expeditionary force, where he particularly stood out.

The legal statute for military chaplaincy are set out in the law of 8 July 1880 which superseded that of 20 May, 1874. Article 2 of the 1880 law stipulates : “Ministers of various beliefs will be present in camps, detachments and other garrisons stationed outside cities”. Drawn up under the Concordat regime, the law concerns Catholic, Protestant and Jewish worship. These provisions were not repealed in 1905 and the law separating State and Church does not apply to military chaplaincy. Various decrees ruling on public administration were promulgated in order to define the status of chaplains in the army. In implementing the rules set out in the 1905 law, the decrees anticipate that chaplains do duty in military bodies and establishments where freedom of worship would not exist without organised chaplaincies.

The ministers of these different faiths are called chaplains. Some have military status while others have a civilian contractual or voluntary status. They are recruited under the title of major which they use, but hold no rank or grade in the military hierarchy.

Three military chaplains, one Catholic, one Protestant, and one Jewish, are appointed by the Ministry of Defence, given the title of army major and oversee all chaplains, be they civilian or military. Chaplains who are not military – Catholic, Protestant or Jewish – and Muslim in the near future – are appointed by the Ministry of Defence on the recommendation of the Military Chaplain.

Transfer requests are submitted to the chief commander of the armed forces by the director of the chaplaincy of one of the three faiths, and cannot be discussed within the administrative jurisdiction as stipulated in the decree of the State Council of 27 May, 1994, of the Protestant chaplain Bourges.

Chaplains in operation

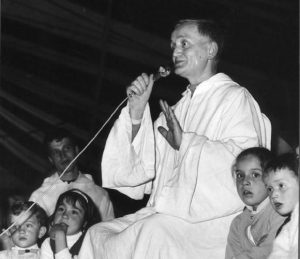

During the First World War Protestant chaplains accompanied troops on the battleground. Pastor Nick who founded the Mission Populaire (Popular Mission) was awarded, along with others, the Légion d’honneur for his outstanding ministry with the soldiers in his division. Pastors did not wear full uniform just parts of it. It was not unusual to see a priest in a mud-splashed cassock ; a pastor might wear civilian trousers and a uniform jacket, his pastoral robe tucked under his arm…

In-between wars chaplaincy was legally recognised in camps, forts and military establishments outside cities.

During the Second World War chaplaincy was organised as it is today. There were chaplains in almost every unit fighting for Liberation, either national, from England or from the French Empire. There were Protestants among the military chaplains during battles for the Liberation, like Hugues de Cabrol for instance who became director of the Protestant chaplaincy in the army.

After the war pastor Sturm settled in Baden-Baden and directed the Protestant chaplaincy in the army. He set up the chaplaincy for the occupation forces in Germany and Austria. His ministry of forgiveness and reconciliation also helped revitalise the German people. He died in office at Baden-Baden a few years later.

At the same time French troops were starting to fight in South-East Asia. French military chaplains were there too and shared a hard life in the most exposed posts, the insecure colonial roads, the fighting. So pastor Tissot came to be dropped by parachute on Dien Bien Phu to minister the troops then encircled by the Vietminh. On the fall of Dien Bien Phu on 7 May, 1954, pastor Tissot was taken prisoner and spent five months in a Vietminh re-education camp before coming back to France and to the EELF (French Lutheran Evangelical Church) in the Montbéliard region.

Then followed the war in Algeria but after that there was peace, at last. The chaplaincy was reorganised to be a legal entity in metropolitan France. The decree of 1st June, 1964 coordinated the existing Catholic, Protestant and Jewish chaplaincies. It followed the regional pattern. It was not until the Force d’Action Rapide was created in 1984 that operational chaplains were to be found exercising their ministry among the military wherever they went, regardless of the danger. Pastor Joël Dutreuil organised the Protestant chaplaincy in the Force d’Action Rapide.

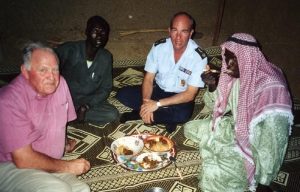

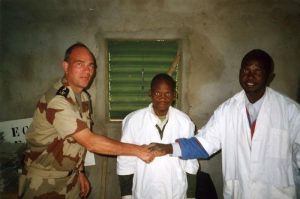

Currently, French Protestant chaplains are with French soldiers in action everywhere within the national, international, U.N. and NATO forces ; in Chad, Central Africa, Somalia, Rwanda, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Saudi Arabia (Gulf war 1990-1991), Lebanon, Cambodia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Albania, Macedonia, t o name but a few.

Protestant military chaplains are also on board ships of the national navy, including when they are operational.