An education system for Protestants

The Protestants wished to create Protestant schools with the help of various Biblical organizations in order to give every Protestant the opportunity of having a personal relationship with the Scriptures. The Secretary of the Society for the Promotion of primary education among French Protestants (SEIPF), founded in 1829, wrote in 1830 that “all Protestants must have the opportunity to read the Gospel, meditate and judge by themselves the sublime truth and the divine teachings that it contains” (chaque protestant puisse lui-même lire l’Evangile, méditer et juger par lui-même les sublimes vérités et les divins enseignements qu’il renferme) ; but this effort “breaks itself today against the boundless ignorance of a large section of the population” (se briser aujourd’hui contre l’ignorance absolue d’une grande partie de notre population – J.-Cl. Vinard, les écoles primaires protestantes en France de 1815 à1885, Montpellier, 2000).

School education policies

Below is a reminder of the successive legal steps taken concerning education throughout the nineteenth century and that form the background of the action taken by Protestants.

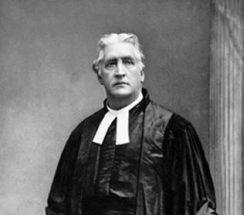

The June 28, 1833 Act, initiated by Guizot, is an essential stage in this evolution. This act makes it obligatory for local governmental organizations to create three types of schools : a primary school in each town, an “advanced” primary school (EPS) in each county or in each town of over 6,000 inhabitants, and a teachers-training school in each “department”. The act acknowledges the free right to teach since anybody with the appropriate degree has the right to open a primary school, but all schools, whether public or private, remained under the control of town or administrative district surveillance committees. In the next few years, a body of school supervisors was created, the original “infant schools”(forerunners of today’s kindergarten schools) as well as courses for adults, which had become more and more popular, were formally organized and – last of all – girls’ primary schools could be opened. However, primary education was neither secular, nor compulsory, nor free until the 1848 Revolution when these principles were proclaimed. The Falloux Act, dating back to 1850, established the freedom of secondary education, suppressed the “Advanced” primary schools and increased the teaching prerogatives of the Church.

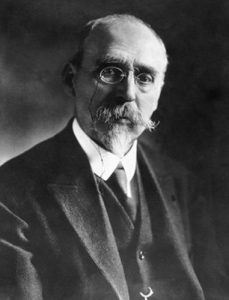

The education policy of the Third Republic – with Jules Ferry and F. Buisson, a Protestant, at the time superintendent for primary education (cf. the Protestants and Republican education) – established free primary education (June 1881), compulsory education for children from the age of six to thirteen, and a secular syllabus (March 1882). This meant that religious education was replaced by civic and moral education. The law establishing the separation of Church and State was voted on December 9th, 1905. As everybody knows, Protestants supported it and “unlike the Catholics, who increased the number of their schools, they had so much trust in the fledgling secular education that, with the exception of the one in Boissy-Saint-Léger, they closed their teacher-training schools and most of their primary schools” (à la différence des catholiques qui multiplient leurs écoles, ils font de confiance dans l’école laïque naissante qu’ils ferment leurs écoles normales, sauf celle de Boissy Saint-Léger, et la plupart de leurs écoles primaries – Marc Bœgner, quoted by J.-Cl. Vinard).

Many private initiatives were taken in areas that were not covered by the public system of education, such as kindergarten schools and vocational schools. These often noteworthy experiments widely contributed to the development of public education.