The reformation of sacred music

In the early 16th century, sacred music in the Catholic Church was sung in Latin by the clergy in the church choir stalls. The reformers aimed at giving music back to the people – to all worshippers, including the women.

Church music was to undergo significant changes, lyrics and music wise.

To enable the congregation to sing, the words had to be in the people’s own language. The texts that were to be sung had to be translated and adapted. The decision was taken to write them in stanzas in metered verse, with a set number of feet.

These texts were either Psalms from the Bible, or based on other Bible passages.

The music

Congregational singing meant relinquishing polyphony which, at the time, was very popular. People sang in unison one syllable per note, and the melody had to conform to the word stress pattern.

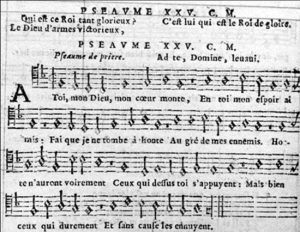

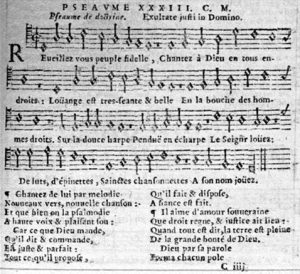

Progress in music printing allowed this new repertoire to spread rapidly. Even though not all worshippers could read, let alone read music scores, the new Psalters helped promote the new repertoire.

The repertoire varied from one Reformed movement to another.

The Lutheran movement

Luther loved music and even composed some. The result was that the Lutheran reformation warmly welcomed music.

Luther said « God announces the Gospel through music also », the Gospel being the Word incarnated in Jesus Christ. Luther wanted the service to be centred on Christ, and thus had new hymns composed that preached the incarnation, the cross and the resurrection. They were named Lutheran Chorales.

The texts were divided into stanzas, at first sung in unison, but later in four parts.

Chorale writing developed widely. The most famous example was « Ein feste Burg » (“A mighty stronghold is our God”) : the words and tune were written by Luther himself.

Neither organs or other musical instruments, nor professional choirs had ever disappeared from Lutheran churches. These enabled a flourishing production of sacred music in the 17th and 18th centuries with composers such as Schütz, Bach, etc. At the time of Johannes Sebastian Bach 5,000 chorales already existed. Bach did not produce new melodies for the Passions but harmonised some of his chorales.

The Reformed movement

The Reformed went further in music reformation and banned any reminder of the clerical stranglehold on sacred music. Choir-stall organs were even done away with.

Worshippers sang ‘a capella’, in unison and without the help of instruments. The reformed repertoire consisted of Psalms.

Why Psalms and why Psalms only ?

Biblical psalms were given by God : it was as if God himself had placed them in the worshippers’ mouths to sing his praise.

The reformed service of worship was focused on the God’s glory – soli deo gloria – and the Psalms were a most adequate expression of this glory. The Lutheran service of worship focused on the person of Jesus Christ and this resulted in the writing of new hymns : the Chorales.

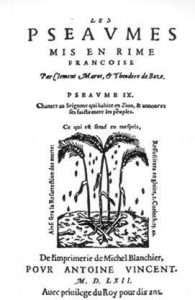

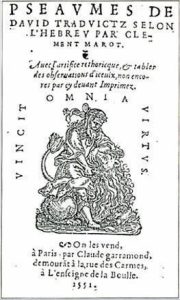

During his stay in Strasbourg with Martin Bucer, Calvin first heard congregational psalm-singing in German. Luther was first to put the Psalms into verse and stanzas in German. In Strasbourg, Martin Bucer did the same with the entire Psalter. Calvin took up the idea and asked real poets – such as Clément Marot and Théodore de Bèze – to write poetry, and real musicians to compose music for a Psalter that was to be known as the Geneva Psalter.

Other Psalters were composed in Lausanne, Basel and Mulhouse, but the Geneva one was best known for the quality of its poetry and music.

The absence of instruments to accompany hymns prompted Calvin to create a specific ministry to lead psalm singing : the cantor. Amongst the best known of these was Loys Bourgeois.

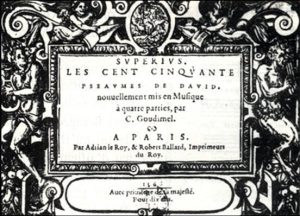

In the late 16th century, psalm singing in three or four parts was practised at home or privately. Claude Goudimel and Claude Lejeune were the most prominent composers who harmonised Psalms.

But the reformed musical production practically ended towards the end of the 16th century.