Calvin's ideas spread throughout France

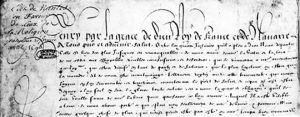

Calvin’s works spread throughout France, especially his Institution of the Christian Religion – the last edition appearing in 1560. This was an immense work written with two objectives in mind : first, to set out a doctrine and then to incite people to actually put these ideas into practice. In this way, the reformed communities, even though they were not allowed to openly proclaim their faith, acquired a clear statement of their religious beliefs, which included the basic tenets of church laws, theology and ecclesial practices.

Growth of the Reformed Churches

From 1555 onwards, many churches used this “Genevan” form of organisation.

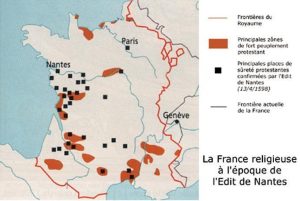

From the beginning, when it first opened in 1559, the Academy of Geneva trained pastors to come to France to make sure that churches were strictly obeying the rules set out in the « Institution ». In the space of five years, about a thousand were set up, especially in the area of Provence, but also south of Poitou, in the Loire country and in Normandy. Between 1559 and 1565 the movement grew considerably – in France there were about two million Protestants, that is to say, some 10% of the kingdom’s population. Some towns such as Montauban were exclusively Protestant. But this spectacular growth did not last long – from 1565 onwards the tide went the other way – it was with the massacre of St. Bartholomew in 1572 that the situation changed radically.

At the end of the 16th century, the number of Protestants had dwindled – there were only one million left ; however, those that remained were active and dynamic, especially in the towns.

The Church was organized on three levels

At local Church level, Protestants met together to elect a council of elders called the “consistory“, which named the pastor. It was “to deal with maintaining order, looking after upkeep, as well as the government of church”.

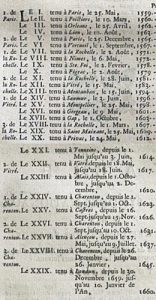

On the provincial and national level, the churches had a totally original institution called a “synod” : it was a gathering of representatives from different churches all over France. These men served as a link between local churches, each of which remained independent and all with equal rights.

An example of political organisation

Protestant thought brought about a concept of power that openly contested absolutism. In the political domain, some thought the people should have sovereign power, represented by the States General – they were called “monarchomaques”. The United Provinces of the Midi represent an interesting application of this theory : a political regime was installed which closely resembled a federative republic. It lasted for about twenty years.