The Alsatian exception

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were about 220,000 Lutherans in Alsace and in the Montbéliard region.

- In Alsace Lutherans accounted for one third of the population, and lived mostly in ancient free cities such as Munster, Colmar, and Wissembourg, but mainly in Strasbourg where 25.000 out of the 38,000 inhabitants were protestant in 1800. There were 160 Lutheran parishes and over 200 active pastors. There were 25,000 reformed and 16 pastors, mainly in Mulhouse -14.000 – which was to remain independent until 1798 and was exclusively reformed.

- The Montbélaird region, which had long belonged to the Wurttemberg prince, comprised four districts, namely Blamont, Clémont, Héricourt and Chatelot, under French sovereignty since 1676 and of the Montbéliard county annexed to France in 1793.

Before 1789, according to the principle cujus regio ejus religio, protestant churches depended on their prince, who organised the ecclesiastical hierarchy: some parishes were tutored by a superintendent, or an ecclesiastical surveyor under the control of a consistory, i.e. ecclesiastical regency, comprising lay people, generally lawyers and theologians ruling in the name of the prince. In free cities, churches were controlled by consistories the members of which were chosen by city authorities. No legal bond unified the various consistories, the role of which could be compared to that of catholic bishops.

The new revolutionary ideas were first welcomed by influential characters such as Oberlin and Blessig. When dechristianizing began, along with arrests of « suspects », services were often forbidden. But sometimes worship went on secretly in clubs, as in Ban-de-la-Roche. Like most French people, Alsatians approved of Bonaparte coming to power and restoring order.

A less divided community

The Concordat in 1802 changed the organisation of Alsatian churches as it had changed the reformed church. As for the reformed church, the Concordat only took into account consistorial churches with six thousand members, but only the wealthier people could become lay members of consistories.

- Five consistorial churches were surveyed by an inspector and an assembly, under strict surveillance, and could only meet in the presence of the prefect or sub-prefect, after government permission. At the head was the general consistory, established in Strasbourg, with a president appointed by the Head of State. They met every five years for a short session, and had very limited power.

- In fact, authority rested with the board of directors, comprising the president of the consistory, two ecclesiastical surveyors, and three lay men of which one was appointed by the Head of State.

That status was readily accepted since it acknowledged the existence of the Church on equal footing with the Catholics, and the pastors were being paid. It did modify the organisation of the Lutheran church, but the new “Augsburg confession church” still had a centralised framework, and an unofficial “pastoral conference” held yearly with all Alsatian pastors which reinforced Lutheran unity.

In March 1848, some ecclesiastical revolution took place in Strasbourg. The board was accused of being anti-republican and forced to resign, then an assembly designed a more democratic organisation of the Lutheran church, that was never adopted.

Louis-Napoleon took office and a decree voted on the 26th of March 1852 reorganised the board, further centralising it. It comprised a president of the superior consistory appointed by the government, 10 of its 27 members being nominated, and the board of directors, 3 of its 5 members being nominated and in charge of administrative matters. Centralisation, however, was not a problem because it had prevailed throughout protestant history.

The debate among liberals and evangelists was never to be as violent as the one among inland reformed. One should keep in mind that though Alsatian Protestants were constantly nagged, their rights indented under the monarchy subdued to the Westphalia Treaty, they had obtained freedom of worship and closely watched intellectual movements in Europe. They never lost the tradition of theological debates, as the works of the German school prove. Despite the action of Franz Haerter and Frédéric Horning in favour of the pietistic-evangelical movement, liberals remained the majority, following great characters such as Blessing and Haffner.

After Sedan

The Frankfurt Treaty on the 10th of May 1871 confirmed the loss of Alsace and part of Lorraine. The board and general consistory, along with the theology faculty remained in Strasbourg. Frédéric Lichtenberg’s message in February 1871 entitled Our duties to France created a great stir, and prompted a move “inland”. The Theology faculty in Paris was created in 1877, and a number of Alsatians were to become teachers there. However, the intellectual bonds between Strasbourg and France were kept, as can be seen in the works of Edouard Reuss, the great university theologian.

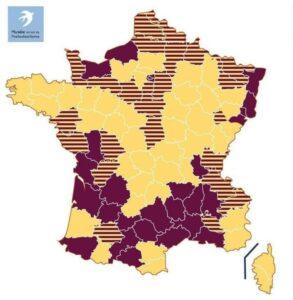

The inland Lutheran community was only 80.000 strong. A synod met in Paris in 1872, and the new organisation, under the 1879 law, observed Lutheran customs, namely both regional synods (Paris and Montbéliard) and one general synod, united through the national Alliance of Lutheran churches. In 1906 the name Church of the Augsburg Confession was changed for the French Lutheran evangelical church.

In 1918, in order to ease the union with the returned provinces, the government decided not to enforce the secession law, thus creating two protestant churches, namely the Augsburg Confession church in Alsace and Lorraine, and the reformed church in Alsace and Lorraine, and both kept their pre-1870 institutions. The new French theology faculty was re-instated, its Dean was Paul Lobstein. Charles Scheer, a francophile pastor in Mulhouse explained the « Alsatian uneasiness » and the importance of acknowledging the religious factor in the assimilation process.

Albert Schweitzer was to make Alsatian Protestantism radiate thanks to his own aura. After 1945 Charles Altorffer, mayor to be of Strasbourg, was trusted with the reorganisation of the church of Alsace and Lorraine, and of the theological faculty renowned for François Wendel.