King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

England had gradually distanced itself from Rome after a strained relationship during the 12th and 14th centuries. At issue were ecclesiastical endowments, increasingly disappearing to Rome. England had already gained some freedom in religious matters before the 16th century.

Moreover, John Wycliff (1320-1384) had denounced the Church’s abuses and insisted on the authority of the Bible he had translated into English. His influence had prepared minds for Reform ideas.

In the early 16th century, humanism had permeated England, and Erasmus (1466-1536) had been teaching at Cambridge University for two years. So he had trained a whole generation of theologians. It was also in Cambridge, in 1520, that Luther’s ideas reached a small group of academics, called “the little Germany”. Among them were Thomas Cranmer and Matthew Parker who both became Archbishop of Canterbury.

The way had been prepared for Henry VIII’s separation from Rome.

Henry VIII's divorce

Postage stamp depicting Henry VIII © Collection privée

Postage stamp depicting Henry VIII © Collection privée

Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509. In 1504, he had married Catherine of Aragon (born in 1485), the widow of his elder brother. Pope Jules II had officially sanctioned the marriage. Catherine gave birth to several children of whom only Mary, born in 1527, survived. The king, who was 36 in 1527, had no male heir. Obsessed by the need for a male heir to ensure the throne’s stability, he decided to ask for a divorce from his ageing wife to marry Anne Boleyn, a young woman he was in love with.

Henry VIII doubted that the Church would approve of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Indeed, as is written in Leviticus 20.21: “Thou shalt not uncover the nakedness of thy brother’s wife: it is thy brother’s nakedness.”

Pope Jules should not have sanctioned that marriage, which had to be annulled. But Catherine’s close relatives referred to a verse in Deuteronomy (Dt. 25.5): “If brethren dwell together, and one of them die, and have no child, the wife of the dead shall not marry without unto a stranger: her husband’s brother shall go in unto her, and take her to him to wife, and perform the duty of an husband’s brother unto her.”

With no clear solution in the content, the debate turned to the procedure: was the pope competent to give a dispensation or not? English kings during the Middle-Ages had already restricted the rights of the Holy See over their country’s Church, and claimed that the royal courts of justice had precedence over papal courts. But only pope Clement VII could annul Henry VIII’s first marriage.

The split with Rome

Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) © SHPF

Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) © SHPF

Until 1527 relationships between Rome and London were harmonious: Henry VIII had even written a book refuting Luther’s theses on the sacrament. Pope Leon X thanked him and gave him the title “Defensor Fidei”. But the request to annul his marriage was a problem for the pope. Indeed, the pope was anxious not to displease Charles V, Catherine’s nephew. The request dragged on for two years, and the king became impatient. Not able to annul his marriage through Rome, he had the divorce pronounced by an English court in May 1533. Clement VII responded by excommunicating Henry in March 1534. The marriage to Ann was celebrated by Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), the new Archbishop of Canterbury. Clergy representatives validated the king’s new marriage under duress.

In November 1534, the “Act of Supremacy” passed by Parliament granted the king and his successors the title of “Supreme Head of the Church of England”. It meant that all ecclesiastical power rested in his hands. The status of the pope was the same as that of the Archbishop of Rome, without any specific authority in England. Archbishops and abbots were no longer consecrated by the pope, but appointed by the king, who was also the only one able to take disciplinary measures and to punish heresies.

The king had an act of parliament passed which led to the dissolution of the monasteries between 1536 and 1540. Their property was gradually confiscated. The Church, who owned one third of the land in England, lost half of it to the Crown whose coffers were empty, or to the king’s close relatives. Monks and nuns left their monasteries, some became priests while others were given a pension.

This upheaval, agreed by Parliament and by the clergy, encountered little resistance, except that of Chancellor, Thomas More. He refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the king and was beheaded in 1535 – but was canonised in 1935.

Catholicism without a pope

Was England going to follow the Protestant path after the split with Rome? A few things would have made you think so: for instance, from 1536 the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed had to be taught in English, and every church in England had to have a Bible in English. That same year the sanctioning of the Ten Articles turned doctrine towards Lutheranism.

But in 1539 the law of Six Articles put an end to the hopes of the Reformers, as it reaffirmed the main points of Catholic doctrine that Luther had criticised.

On Henry VIII’s death the Church of England was not a Protestant Church but a Catholic Church without a pope.

The reign of Edward VI (1547-1553)

The Book of Common prayer (1550) © Justus.anglican.org

The Book of Common prayer (1550) © Justus.anglican.org

Edward VI, the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, was 10 when his father died. The regent, Lord Somerset, was in favour of Protestantism. He was a friend of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, who was also attracted by Reformation ideas.

As early as 1547 Reformation ideas could be publicly preached, and acts of parliament gradually imposed new practices: communion in both kinds, removing statues and altars from churches, then the allowing of married priests. In 1549 mass in Latin was abolished, to be replaced by the liturgy in English using Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. It remained in effect in the Anglican Church until the 20th century. The ritual of mass was simplified, but not done away with altogether. Some customs, such as wearing clerical robes, were kept to ease the transition for worshippers. But the liturgy was clearly Protestant, influenced by the ideas of Luther and Bucer. This new liturgy shaped the devotions of the English through the centuries.

Many reformers came from the continent – John Knox became Edward VI’s chaplain; Martin Bucer, the reformer from Strasbourg, became a professor at Cambridge University; Pierre Vermingli, an Italian, won over by Zwingli‘s ideas, became a professor at Oxford. Thanks to their influence Reform ideas spread. In 1552 Cranmer revised the Prayer Book, taking into account some of Bucer’s criticisms about the liturgy and Holy Communion. It was also in 1552 that he clarified the new doctrine in his “42 articles” largely inspired by the Reformation.

The reign of Mary Tudor

The Holy Bible – Bible translated into English in Geneva in 1560 (during Mary Tudor pde Marie Tudor) © Collection privée

The Holy Bible – Bible translated into English in Geneva in 1560 (during Mary Tudor pde Marie Tudor) © Collection privée

Edward VII died young and his step-sister Mary ascended the throne. She was the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, and a devout Catholic. Helped by Cardinal Pole – the pope’s legate whom she later appointed Archbishop of Canterbury – she tried to restore Catholic worship as well as adherence to Rome. All reforms passed under Edward VIII were repealed. Many priests and bishops were dismissed. Opponents were sentenced to be burnt at the stake: 300 or so between 1555 and 1558, including several bishops and even Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury. This earned her the name “Bloody Mary”. The courage of the martyrs provoked the crowds’ sympathy and hatred towards Rome. It was a paradoxical situation since the queen was not on good terms with Pope Paul IV so a few bishoprics had remained vacant. Upon Mary’s death, since she had had no children, the idea of restoring Catholicism in England disappeared.

The reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603)

Postage stamp depicting Elizabeth the First © Collection privée - Reproduction Parc national des Cévennes

Postage stamp depicting Elizabeth the First © Collection privée - Reproduction Parc national des Cévennes

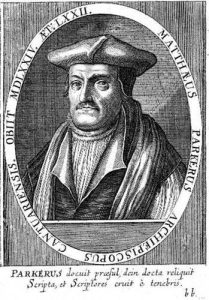

Matthew Parker by Theodor de Bry © Bibl. du Séminaire évangélique de Wittenberg

Matthew Parker by Theodor de Bry © Bibl. du Séminaire évangélique de Wittenberg

In 1558 Elizabeth I, the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, became queen. She was 25. Her religious beliefs have remained a mystery to historians. She rejected both Calvinism and Catholicism. She was brought to power thanks to the Protestants and wanted peace in her kingdom. She achieved this with the Religious Settlement, which Parliament passed in May 1559 by just 21 votes to 18. The Church of England was established at the wish of the sovereign and Parliament and was a national Church, independent from Rome and Geneva. It remained a medieval Church in its administration, institutions and laws, but became a Reformed Church in its doctrine and liturgy. That is why Anglicanism is often called the middle way.

The Settlement comprised two parts:

- The Act of Supremacy reinstated the act of Henry VIII: the queen was the Supreme governor of the Church. She controlled all the activities of the clergy. She appointed the dignitaries and could take disciplinary measures in accordance with the laws passed by Parliament.

- The Act of Uniformity dealt with the liturgy to be used in every church in the land. It was the liturgy of the 1552 “Prayer Book”, but modified to be more conservative in the hope of winning over those closer to Catholicism. The use of vestments was kept, as well as the word priest, but the altar was referred to as the “Communion Table”. The celebration of Communion could be either more traditional or more Reformed. The use of bread was forbidden, but wafers were allowed. The exclusive use of English in Church was widespread, and the population was supposed to attend Sunday service, and to receive Communion according to the new rite. Those who refused were called “recusants”, and were liable to a fine, to imprisonment, or even sentenced to death if they were repeat offenders.

In 1563 the doctrine of the Church was defined in an Act of Parliament known as the “Thirty-Eight Articles” which became the “Thirty-Nine Articles” in 1571. It was clearly Protestant-orientated, but it is difficult to determine whether it was more Lutheran or Calvinist. It was mainly against Papists and Anabaptists.

Elizabeth dismissed the bishops appointed by Mary Tudor, who refused to take the oath of allegiance to the sovereign. She replaced them with new bishops, some of whom were returning from exile in Europe and had been influenced by ideas from Geneva or Zurich. The queen appointed Matthew Parker (1504-1575), a moderate like her, as Archbishop of Canterbury. The queen’s cautious religious changes are explained by political necessity: until the defeat of the invincible Armada in 1588, she had to remain an ally of Philip II of Spain in order to protect the country from France.

During Elizabeth’s reign, the clergy and the people gradually became Protestant: competent clergymen were trained at Cambridge and Oxford universities, while itinerant preachers travelled the country. Many catechisms were published, and reading the Bible was encouraged – the most widely used version was the Geneva Bible, liked because of its notes and commentaries.

Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign most English people had joined the established Church, but tensions remained between those who wanted worship to be more Catholic and those who wanted things to be simpler, more in the Swiss style. Those who wanted a more Reformed church, with a Calvinist doctrine, were called “Puritans”.