Cambridge great Ste Mary's church © Collection Privée

Cambridge great Ste Mary's church © Collection Privée

Profoundly shocked by the violence of the French Revolution, at the beginning of the century, English society and the Church of England took refuge in conservatism. However, this changed in the 1830s and in 1838 Catholics could at last become civil servants, and in 1839 they could stand for Parliament, along with non-conformists. In 1830 the Whigs came to power and immediately began to deal with the corruption in the Church of England, and particularly the grossly unfair distribution of its wealth. There were riots against the clergy especially bishops, but also vicars who held several ecclesiastical benefices concurrently and did not reside in their parishes. In 1835 a commission was set up to reform the Church and rid it of the worst of this inequality. Although it took a long time for this reform to come into effect, it meant that the Church had to be run on more modern lines. Alongside this reform imposed from outside, a Reform movement grew up within the church, known as the Oxford Movement.

The Oxford Movement

J.H. Newman © Collection Privée

J.H. Newman © Collection Privée

This movement was a reaction to the increasing secularisation of society and the challenge to the bishops’ authority from within the Church. Its main leader was John Henry Newman (1801-1890), a fine preacher, who, with his friends, was at the heart of a new High Church spiritual Revival movement, the High Church being the wing of the church very attached to liturgy and the Prayer Book. He insisted on the apostolic succession within the Church of England and, in 1841, demonstrated that the 39 Articles, the very foundation of Anglicanism, could also be interpreted from a Catholic point of view. This gave rise to a deep controversy within the church obliging Newman to resign and, in 1845, to convert Catholicism. The movement survived but concentrated more on ritual – it also introduced liturgical practices which had much in common with Catholicism. Supporters were called “Anglo-Catholics”.

The Evangelicals

Bible sent to Madagascar by The British Bible Society during the persecution (1835) and hidden in th © Bibl. de la Société Biblique britannique et étrangère

Bible sent to Madagascar by The British Bible Society during the persecution (1835) and hidden in th © Bibl. de la Société Biblique britannique et étrangère

Towards 1850, about a third of the Anglican clergy were Evangelicals. The movement became even more powerful when many Evangelical bishops were nominated, although this did lead to a certain amount of friction in some dioceses. The Evangelicals achieved enormous progress in social reform ; they fought against alcoholism and prostitution ; they also set up an education system to help the poor. A major missionary society was started which worked throughout the British Empire, and then the Bible Society which enabled the Bible to be read all over the world thanks to its translation into many local dialects. They fought against corruption in public life and endeavoured to establish the Sabbath as a day of rest, forbidding any form of work. However, their strict, moralistic attitude, reinforced by the example of Queen Victoria, went too far and caused an adverse reaction against them by some people.

Religious liberalism : the Broad Church

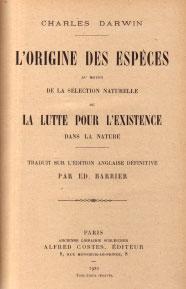

Darwin, The Origin of Species, title page

Darwin, The Origin of Species, title page

Scientific progress, and especially Darwin’s book on the origin of species (1859), led to conflict between science and religion. In addition, the German style of biblical criticism, which came to England in the 1860s, also had a strong influence. Seven theologians wrote a book defending these ideas, which stirred up a violent reaction; however, around 1875 this died down.

The supporters of the Broad Church, who believed in scientific progress, and this new style of biblical criticism, advocated an anti-dogmatic, tolerant, inclusive Church which welcomed the Non-Conformists. They often worked together with the Christian Socialists, who strove to reconcile faith and social justice.

The Lambeth Conferences

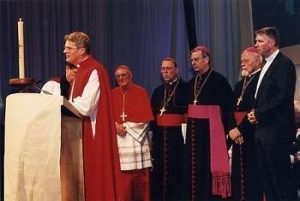

The Lambeth Conference (1998) © J. Solheim - episcopalchurch.org

The Lambeth Conference (1998) © J. Solheim - episcopalchurch.org

In order to maintain unity between the various different Anglican Churches of the British Empire, a conference gathering together all the Anglican bishops was held in Lambeth in 1867, presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury. At the third conference, the Quadrilateral agreement of Lambeth was adopted, defining the basic tenets of the Anglican Church: faith based on the Bible ; the Apostle’s Creed and the Nicene Creed as the basis of belief ; two sacraments, baptism and the eucharist ; the historic episcopacy.

These conferences, which continued to be held every ten years, openly discussed topical subjects concerning the Churches of the Anglican Communion.

The Free Churches

Lymeregis (GB, Dorset), congregational chapel © Collection Privée

Lymeregis (GB, Dorset), congregational chapel © Collection Privée

At the end of the 19th century, the dissenters, or Non-Conformists were renamed the Free Churches. They included the XVIIth century dissenters (the Congregationalists – also called the Independent Church – the Baptists, the Presbyterians, the Quakers), and the 18th century dissenters (the Methodists).

In 1828, the Act which enabled the Non-Conformists to stand for Parliament was the beginning of a long struggle for equality with the Anglicans (for example, they were only allowed to go to university in 1871).

The number of Non-Conformists increased gradually throughout the century and they built many chapels. The Congregationalists and Baptists doubled their numbers, but the Presbyterians lost much of their popularity and many became Unitarians, that is to say, they rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. Due to an internal conflict, the Methodists lost many of their number around 1840, but regained them later.

The first congress to assemble all the Free Churches together was held in 1892; in 1896 this became the Council of Evangelical Churches, which existed to further a better collaboration between its various members.