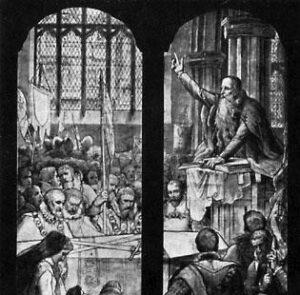

The Reform movement became established in Geneva

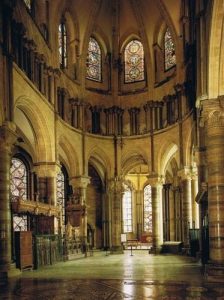

At the beginning of the XVIth century the town of Geneva was an independent state. It was influenced by Luther’s ideas from 1525 onwards and William Farel’s sermons led to the setting up of the Commune, which was powerful in the town, establishing the Reform movement in 1536. The same year Jean Calvin, author of the already well-known Institution Chrétienne, was asked to come to Geneva to strengthen the Reform movement and to transform the town according to Scriptural principles. There were many factors which contributed to Geneva being called “protestant Rome” : the wave of incoming refugees from France, Italy, England or the Low Countries, the Academy, set up in 1559, which taught many foreign students, lastly, the activities of Théodore de Bèze, who worked with Calvin and later became his successor. The institutional model of the Genevan Church, with its ecclesiastical rule by a pastor, an elder and a deacon, became typical of all reformed churches.

The Swiss cantons

During the same period, the Reform movement also became established in the largest Swiss cantons : Zurich, Bale and Berne (this included what is now the canton of Vaud with its capital Lausanne). In Zurich, Zwingli (1484-1531), who played an essential role in the Reform movement, developed a theological standpoint which differed from Lutheranism over the issue of the Last Supper ; in fact his theses were close to those of Calvin at a much later date in his doctrine of predestination.

On the whole, the Reform movement took hold in the towns, while the rural and mountain cantons remained catholic and, with the support of the pope and the emperor they formed a Christian union. The “first war of Kappel” (1529) ended in a compromise but Zwingli, ill pleased with the results, called for a second war ; this time, at the second battle of Kappel, the Zurich armies were badly defeated by the Catholics and Zwingli was killed (1531). The peace treaty which followed laid down the basis of religious division in Switzerland : on the one hand the four reformed cantons (Zurich, Berne, Bâle, Schaffhouse), on the other the seven catholic cantons (Uri, Schwyz, Unterwald, Lucerne, Zoug, Soleure and Fribourg). Glaris and Appenzell were of mixed religion. The catholic cantons, contrary to their protestant counterparts, were quite poor and with a relatively small population, but nonetheless they

had the majority of seats at the federal Diet and this catholic opposition would prevent the Confederation from expanding for a long time ; Geneva, an independent town, was only attached to it in 1815.

As for the Protestants, their religious structure differed from place to place : in Geneva, ecclesiastical rule was in the hands of the Consistory, in Zurich civil government had a certain amount of influence. Conflict came to an end with Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), the “patriarch of reformed Protestantism”. The drawing-up of the New Helvitic Confession (Confession Hélvétique postérieure) (1566) was to be the definitive basis of Swiss Protestantism.

The XVIIth century and the triumph of the «reformed orthodox Church»

At the beginning of the XVIIth century, the Catholics tried to restore their faith. Geneva remained independent and held out bravely against the military attacks of the Duke of Savoy – finally, its victorious resistance on the night of the “Escalade” (December 1602), led to freedom from the control of Savoy and reinforced its influence in Europe.

However, in southern and eastern Switzerland the Counter-Reform movement gathered momentum, under the leadership of Charles Borromée, archbishop of Milan, whose ecclesiastical jurisdiction extended into part of the territory of the Confédération. Catholicism returned to the cantons of Glaris, Appenzell and les Grisons, while Jesuit colleges opened in Lucerne and Fribourg. Religious conflict continued to hold sway because the Protestants, who were twice the number of the Catholics, did not have the majority of seats in the Diète. The peace treaty of Aarau (1712) brought to an end the armed conflict of Vilmergen and established freedom of religious belief in the bailiwicks of mixed religion.

The synod of Dordrecht (1618), gathered together representatives of European reformed Churches and could be considered as the first international Calvinist assembly. Swiss theologians voted the synod’s decisions concerning predestination. This trend of “reformed orthodoxy” established a scholastic basis for the theology of Calvin and Théodore de Bèze.

By the middle of the century, the situation had stabilized : Switzerland remained a country of two religions, with rather more Protestants than Catholics. However, in most cantons, only one form of religion was officially recognized. At the treaty of Westphalia, the independence of the Swiss Confederation was officially recognized.

Above all, the Swiss reformed cantons, and especially the Republic of Geneva, became the refuge of persecuted Protestants, said to be 80,000 in number, who were mostly French Huguenots. They contributed greatly to the spiritual development of Geneva and also to economic progress in the cantons.

It is worth noting that the Swiss cantons did not take part in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648).

The XVIIIth century and the «Enlightenment»

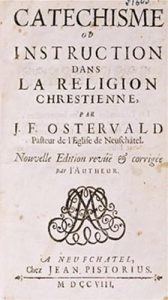

While the pietistic movement was seeking to established itself in Zurich and Bâle, other theologians, such as the pastor Jean Frédéric Osterwald (1663-1747), were advocating a “liberal orthodoxy” which was less narrow-minded. In the second part of the century, theology was greatly influence by Voltaire and Rousseau, who were both often quoted in sermons at this time. The “enlightenment theology” with its emphasis on reason, had come a long way from Calvin’s theses (in particular in its attitude towards predestination). But Geneva continued to consider itself a protestant city in the constitution of 1794, it was proclaimed that only protestants could become citizens.

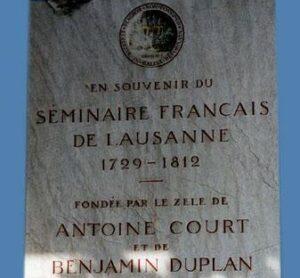

In Lausanne in 1726 Antoine Court established the “Seminary of Lausanne”, which for nearly a century trained pastors for the “Désert”, who went to preach at secret assemblies in France until the Revolution.

The XIXth century : the Revival movement in Geneva in opposition to the Company of Pastors (Compagnie des pasteurs)

The students of the Faculty of theology in Geneva reacted against this “theology of the Enlightenment” in 1910 by setting up a Revival movement. Among these were Ami Bost, Henry Pyt and César Malan. Under the influence of the Pietists and Methodists, they questioned the importance of Reason, preferring a more emotional kind of faith, a return to Calvinism and Bible reading. They were encouraged by Anglo-Saxon preachers as well as Madame de Staël and Benjamin Constant, who advocated a “religion of the heart”.

There was strong opposition between the followers of the Revival movement and the Company of Pastors of Geneva. Some pastors, such as César Malan, were relieved of their functions. The first independent Church was founded in 1818 in Bourg au Four. The Oratory Chapel was founded in 1834 under the auspices of the the Evangelical Society (Société Evangélique). Several pastors or evangelists from these Churches tried to introduce a Revival movement into French Protestantism. Ami Bost in Alsace, Henri Pyt in the Isère, Felis Neff in the Hautes Alpes ; César Malan made several missionary trips to France and many other countries in Europe. Alexandre Vinet (1727-1847), professor at the theology Faculty of Lausanne, one of the greatest theologians of the XIXth century, published “Du respect des opinions” (In respect of Opinions) in 1824 ; he tried to defend the point of view of the revivalist pastors while also respecting the ideas of the Enlightenment, thus maintaining a variety of different opinions. He was much appreciated in France, where his pastoral theology continued to be read by every pastor until the middle of the XXth century.

Sadly, conflict continued between the two religions : a short war in 1847 ended in victory by the Protestants over the separatist catholic cantons which were united together in the Sonderbund. The Swiss Federal State was definitively recognized in 1848.

The beginning of the XXth century : the development of non-religious movements

In order to re-establish equality between Protestants and Roman Catholics, the law of 1907 separated the Church from the State, who took control of the education system.

During the various different wars of the XXth century, Switzerland remained neutral – its position had to be reaffirmed several times. The writer Denis de Rougemont (1906-1985) among others, insisted on the importance of the European cultural heritage and worked at establishing the European Movement. In spite of this, the country has remained obstinately out of Europe. The identity of Switzerland as a defender of freedom in all fields, in particular bioethics, was reinforced by the existence on its territory of many organizations, some of which were ecclesiastical ; among the most important of these is the Ecumenical Council of Churches, the International Reformed Alliance and the International Lutheran Foundation, and non-religious structures such as the Red Cross.

The reformed Churches in each canton are separate and independent from each other, with different statutes according to each canton. Some are practically independent while others have a structure on the lines of the Concordat (i.e. controlled by the State).

In 1920, they became the Suisse Protestant Federation (Fédération des Eglises Protestantes en Suisse), which now includes, apart from 24 cantonal Churches, free evangelical Churches and the Methodist evangelical Church of Switzerland.

In 2005, out of a population of 7.2 million, there are 2.5 million Protestants and 3.2 million Catholics.

Switzerland has been a country with a protestant majority for a long time ; today there are about 40 per cent protestants and 60 per cent Catholics, the reason for this probably being the immigration of a large number of Catholics into the country.