The Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia was established in the XIIIth century. It consisted of Bohemia and Moravia and belonged to the Germanic Holy Roman Empire. It was at its height in the reign of Charles V (1345-1378), who was elected Emperor of the Holy Empire.

Charles V’s son, Wenceslas IV (1378-1419) was also elected Emperor ; however his reign was beset with revolts and a major political crisis, ending when the Elector Princes forced him to renounce his title of Emperor in 1400. A succession of epidemics also wrought havoc in the kingdom. The Black Plague, the “great pestilence” of 1380, which is recorded in history, annihilated nearly 10 per cent of the population. Panic was such that people thought the end of the world was coming.

During this period, the clergy (churches and convents), took possession of more and more land, owning nearly half the territory, making the nobility jealous and the people indignant. However, at this time the power of the Catholic Church was weakened by the “Schism of the West” (the Great Schism) and rivalry between the three popes – one in Rome, one in Avignon and the third appointed to the Council of Pisa.

It was in such troubled times as these that Jean Hus came onto the scene.

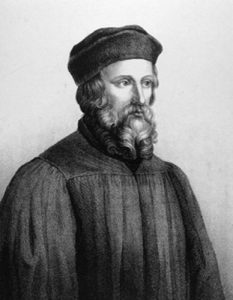

Jean Hus (1371-1414)

Jean Hus was born into a poor farming family and studied theology at Prague University. He became Rector of the University and chaplain to the Court. When he preached in Czech at the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, he caused a considerable stir amongst the local population. In 1390, he began to read texts written by the Englishman John Wycliffe (1324-1384), (who had been excommunicated for heresy by Pope Gregory XII), because he had already begun to criticize the wealth of the Church in England. Jean Hus became an avid reader of Wycliffe’s works and wrote a commentary on them, concerning himself mainly with delivering nothing but the simple message of the Gospel which was against social oppression, corruption and the inordinate power of the Church. As a true disciple of Wycliffe, he considered the Bible to be the supreme spiritual authority which enabled him to see the corruption in the Roman Catholic Church for what it was : the cult of the saints, transubstantiation, and before long indulgences. Although he was excommunicated in 1410, he was able to remain in Prague under the protection of King Wenceslas IV.

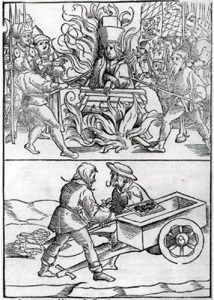

When indulgences were sold in Bohemia in order to finance a war between the Pope in Pisa and the King of Hungary, Jean Hus protested. He had to break off relations with the king and leave Prague to take refuge in southern Bohemia. In 1414, he went to the Council of Constance which had been held to try and put an end to the Great Schism. Here, he defended his point of view and put forward his ideas for reforming the Church. Indeed, the Emperor Sigismund Ist (1410-1443) had granted him safe conduct to guarantee his safety. However, when he reached Constance he was arrested and imprisoned. He was ordered to retract but refused. He was accused of heresy and burned at the stake on 6th July 1415.

The War of the Hussites

Hus’ martyrdomsparked off a violent reaction against Sigismund in Bohemia and provoked a climate of revolution. In July 1419, several of the Emperor’s councilors were thrown out of the windows of the Town Hall by members of the crowd. This “first defenestration of Prague” started the period of Hussite Wars ; Catholics fought against “heretics” but the two Hussite factions also fought amongst themselves. Jean Hus’ followers could soon be seen as falling into two groups : the moderates and the extremists. The former known as the “Utraquistes” believed in communion in both kinds (receiving both bread and wine). The latter, the “Taborites” refused to obey any form of authority, whether religious or political and only accepted to be governed by the laws of the Bible.

For nearly twenty years the Hussites stood up to the imperial army. However, when the moderate “utraquiste” faction joined the opposition, the extremist “taborites” were no longer able to survive. After the treaty of July 1436, the “utraquistes” returned to the Catholic Church but preserved some independence for their clergy in order to shield them from corruption and insisted on the right to receive both the bread and the wine at communion.

The influence of the Hussite Reform Movement and the Protestant Reform Movement

There followed a period of religious tolerance. In 1457 a new Hussite Church, the United Brotherhood was set up, which advocated pacifism. It broke off relations with Rome and with the “utraquistes” drew up its own catechism and appointed its own bishops. Its symbol was the communion chalice (which represented communion in both kinds) standing in front of a Bible (which represented the supreme authority of the Bible, above that of the Pope and the Church). Little by little it evolved and eventually became a Protestant Church.

In 1526 the Kingdom of Bohemia was re-conquered by the Hapsburgs of Austria, although it did manage to retain a certain amount of independence. Luther’s ideas began to penetrate the country from 1520 onwards, and the German Lutheran princes influenced the Czech nobility to such an extent that many were won over by the Reform Movement. In addition, the United Brotherhood sent delegates to Strasburg to meet Bucer and, a generation later, many of its members were drawn to the ideas of Calvin. Although the Huguenot Psalter was translated into Czech, the United Brotherhood did not actually become a Reformed Church. They did, however, manage to achieve the union of all non-Catholics in opposition to the absolute power of the king and, in 1575, a common confession of faith was drawn up, the “Confession of Bohemia“.

In the reign of Emperor Rudolph II (1576-1612), who resided in Prague, the Protestants held many key posts in the municipal councils. The Emperor was keen on art and science ; he brought eminent scholars, such as the astronomer Johannes Kepler, a Protestant and a theologian, to Prague University. The Lutheran merchants helped to build up a thriving commercial link with Germany. Thanks to the official letters of recommendation, signed by Rodolphe II in 1609, the various different Churches stemming from the Czech and Protestant Reform Movements were officially recognized.

At the end of the XVIth century, 85 per cent of the Bohemian population was Protestant.

The defeat at White Mountain

When Rodolphe II died in 1612, leaving no direct successor, the Diet decided to give the Bohemian crown to Archduke Ferdinand of Styria (a Hapsburg), a former pupil of the Jesuits and an ardent advocate for Catholicism. The Czechs reacted violently to this nomination. On 23rd May 1618, they invaded the Royal Palace in Prague, and threw out of the window the two imperial governors from Vienna. Although they came to no harm, this incident sparked off the Thirty Years War.

In 1619, Ferdinand of Styria was elected Emperor Ferdinand II and the States of Bohemia rose up in revolt. They decided to elect another king, Frederick of the Palatinate, whose family had turned to Calvinism.

With the support of Spain and the Papacy, Ferdinand II advanced towards Prague with a well-trained army led by Maximilian of Bavaria. The battle against the Czech Protestants took place on 8th November 1620 at the entrance to Prague, on “White Mountain” : in less than two hours the Protestant troops were overcome. The leaders of the rebellion were arrested and shot.

The defeat at White Mountain was a crucial event in Czech history, the moment when Bohemia lost its independence and religious freedom. From then on, their national history would be divided into what happened before and what happened after this incident.

The Secret Church

From that time on Roman Catholicism was the only permitted religion. The clergy of the United Brotherhood, the nobility and the middle class Protestants had to convert to Catholicism or go into exile. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 (which brought to an end the Thirty Years) forced the Czech territories to join the south, which was Catholic and belonged to the Hapsburgs. This was the beginning of the Counter Reform movement, when the country was forced to convert to Roman Catholicism. Many baroque churches were built in Prague at this time.

The “Protestant” serfs were not allowed to leave the country. They had to convert to Catholicism, and the clergy saw to it that they were “obedient” converts. This time, known as the “Days of Darkness”, lasted for 150 years until the Edict of Tolerance in 1781.

However, a Secret Church was formed. People worshipped in private houses or secret assemblies and services were held according to the rite of the United Brotherhood. Remote regions, and in particular that of Velkà Lhota, resisted the Counter Reform movement in spite of threats : rebels were sentenced to hard labour, or even slave ships, if they were caught in the act of taking communion in both kinds. Preachers, and those who organised the assemblies, could be condemned to death. Even though the repression intensified in the reign of Charles VI (1711-1740), this actually resulted in a strengthening of links between members of the Secret Church.

The Refuge

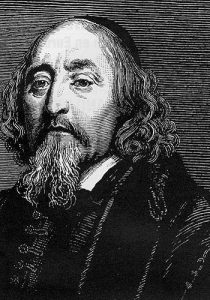

In the decade following the defeat at White Mountain 600 families left the country. What’s more, throughout the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries people continued to go into exile, in spite of the risks involved and the fact that it was illegal. The Bishop of the United Brotherhood, Jan Amos Komensky, whose name was latinised as Comenius (1592-1670), a man who was famous throughout Europe for his literary and educational work, fled to the Low Countries. From there, he would often visit other communities in exile to give them his support.

Refugees fled to several different, but usually adjacent, countries : Saxony received many of them but they did not always find a warm welcome there because they refused to join the Lutheran Church ; there was a large refugee community in Berlin ; in Slovakia they were generally well received and often helped by the Hungarian Calvinists. Some emigrated to Poland and towards the Ukraine, where some communities still speak Czech even today.

In the XVIIIth century Count von Zinzedorf welcomed refugees from Moravia onto his country estate in Herrnhut (to the north of the Czech border). They set up the community of the Moravian Brothers which gave a new lease of life to the United Brotherhood.

This thriving community was also influenced by German pietism. It sent missionaries abroad to set up new communities in many countries : the Caribbean, South Africa, North America and Greenland. They also influenced other Protestant communities, in particular the beginnings of Methodism.

The Edict of Tolerance (1781)

Emperor Joseph II (1780-1790) passed reforms which were to transform the Hapsburg Empire. He abolished serfdom and, with the Edict of Tolerance of 13th October 1781, gave the Lutheran and Reformed Churches freedom of public worship. However, this edict caused problems for the Czech refugees, who had not adopted the Lutheran or the Reformed faiths ; most of them finally decided to join the Reformed Church. Foreign pastors came to serve in these new communities. The Lutheran pastors spoke German and were understood by the local population. The Reformed pastors spoke Hungarian and were not understood, so they had to learn to speak Czech ; this meant that the Reformed Churches developed more slowly.

Some Czech refugees did not join either Church but continued to worship in secret – indeed in some remote regions they were not even aware that the Edict of Tolerance existed.

The Lutheran and Reformed Churches, known as the “Churches of Tolerance”, had to abide by a number of restrictions, which prevented their expansion.

In the second half of the XIXth century, many Czechs would have liked to set up a united Protestant national Church, but this did not come about until the country gained its independence in 1919.

Modern times

From 1800 onwards a conflict began to develop between use of the German language, which declined, and the Slavonic languages, which increased. This was only the beginning of conflict.

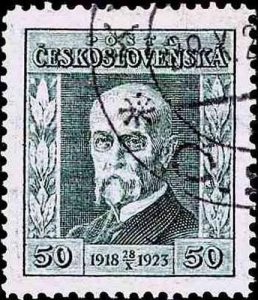

After the First World War the treaties of Versailles and Saint Germain. (1918/1919) caused the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Republic of Czechoslovakia was born : it consisted of Slovakia and the former territories of the Kingdom of Bohemia, (although this seemed somewhat arbitrary). At the same time a violently anti-Catholic movement began to influence the country, because the Catholic Church was thought guilty of betraying the Czech nation when they supported the Hapsburgs. There followed the paradoxical situation where the Czechs, although predominantly a Catholic nation, came to accept an interpretation of their national history by a Protestant, Palacky, who established Jan Hus as a central figure. A statue of him was ordered and now stands in the main square of the old town of Prague. Thomas Masaryk (1850-1937), father of the Czech Republic, became a Protestant. He was a deeply religious man and considered that the Hussite movement truly embodied the Czech national identity. He chose a phrase of Jan Hus’ as the national motto : “truth will triumph”. In spite of this, in 1910, when a census of the population was made, only 4 per cent were Protestant.

In 1918, the general Assembly of Czech Protestants voted (apart from certain Lutheran communities) in favour of the unification of the Czech Lutheran and Reformed Churches, under the name of the Evangelical Church of the Czech Brotherhood (ECCB).This Church renewed former links with the Hussite Reform Movement and the United Brotherhood ; it had a Presbyterian synodal system of government.

In 1920, a Czech Hussite Church came into being ; in churchmanship it sat mid-way between the Catholic and Protestant Churches. Some “modernist” priests, wanting to reform the Czech Catholic Church, had been accused of heresy by Rome, so they decided to found their own national Church. The Czech Hussite Church expanded considerably and now has one hundred thousand members and two hundred and fifty pastors, a hundred of whom are women.

The Second World War and Soviet occupation

Czechoslovakia came under German influence once more with the invasion of the Nazis in 1938 – the Nazis were authoritarian and violent : these were hard times for the Czechs.

As a result of the dividing up of territories by the Treaty of Yalta, Czechoslovakia came under Soviet occupation. The Communist dictatorship soon tried to put down the Church. However, in spite of persecution, the Protestant and Catholic Churches managed to survive : the Catholics in the “Movement of Priests for Peace”, and Protestants in the “Christian Confederation for Peace”. After the Prague Spring (1968), and the “normalisation” which followed, resistance movements grew up, supported by both Churches.

With the fall of Communism, Slovakia was divided into Bohemia and Moravia, which formed the Czech Republic.

Protestant Churches today

Today, only a third of the population call themselves Christian and faith is on the decline. 96% of these Christians are Catholic and 4% Protestant.

The largest Protestant Church is the Evangelical Church of the Czech Brotherhood, which stems from the unification of the Lutheran and Reformed Churches. It has 120 000 members and 230 pastors (55 of whom are women), who receive their theological training at the Theology Faculty which is part of Prague University, and are paid by the State. Diaconal service has a very important place in the Church.

The Lutheran Church has 30 000 members with 37 pastors.

The Baptist Church expanded in the XIXth century and the Pentecostal Churches in the XXth century.

Protestantism in Bohemia

and Moravia (Czech Republic)

1042, 254 01 Libeř, République tchèque