A permanent and open-minded interest in methods of education

As from the XVIth century, the Reformation is strongly linked to education of the masses :

- free access to the Bible demands the development of reading skills,

- confidence in the positive consequences of wider access to education : the more educated the people are, the sooner they will abandon “Roman Catholic superstitions”.

Religious individualism and the prominent place given to meditation arising from the reading of books made education necessary : « One of the essential aims of the Reformation was to educate the people… It wanted every man to be able to read, and which book ? The very book from which it drew its life. » (c’est la Réforme qui s’est passionnée pour l’instruction du people… Elle a voulu que tout homme sût lire, et quel livre ? Celui où elle-même puisait la vie, Jean Jaurès, 1911).

During the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, great Protestant pedagogues renovated thought on education : Comenius (Czech), Oberlin (Alsatian) and Jean Jacques Rousseau.

At the beginning of the XIXth century the example set by Protestant countries such as Germany, England, or The Netherlands caused a great impression on French educators bent on renovating the school system. When G. Cuvier – himself a Protestant – visited schools in Germany and The Netherlands, he was amazed at their advanced methods of education. Protestants founded several religious societies aimed at promoting such methods. One of the first was the Société pour l’encouragement de l’instruction primaire parmi les protestants de France (1829).

The two significant periods of the XIXth century that saw active Protestant participation in the development of public Education were the July Monarchy and the Third Republic.

Organization of Public Elementary Education

The July Monarchy

On several occasions the Ministry of Public Education was entrusted to Protestants : Guizot from 1832 to 1836, Claramond Pelet de la Lozère in 1836, and Guizot once more in 1836 and 1837.

After founding the Annales de l’Education promoting Swiss and German methods of education in France, Guizot promulgated the first major law on public Education (28 June 1833). This law did not make education free or compulsory, but it enforced the building of three types of schools by the local authorities : a primary school for boys in every town and village, an advanced primary school in the chef-lieu (administrative centre) of each département, or in every town with more than 6000 inhabitants, and a Training College for primary school teachers in every département. It establishes a distinction between

- private schools, generally run by a member of the Roman Catholic clergy, but there were also some Protestant private schools (see Protestant Education),

- Écoles communales (public schools in towns and villages), where a Roman Catholic priest may teach. They were run by a school board of which the Protestant pastor, if there was one, was a de facto member. This helped dispel the old fear of Protestant children being forcibly “converted” at school. Mme de Maintenon is said to have declared in 1685 : « I may not get the parents, but I will get the children ! ».

Napoleon had left Primary school education to the care of the Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes. By creating Training Colleges for Primary school Teachers, Guizot opened the way for undenominational education.

Was free, undenominational and compulsory primary school education based on a Protestant model ?

The Third Republic

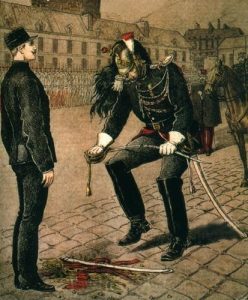

With the defeat of 1871 arose the need of a real, critical re-assessment of the situation, including the shortcomings of public education. In his book La Réforme intellectuelle et morale (1871), Renan saw the quality of protestant Germany’s education as a major reason of its success and advanced the theory that in case of conflict or peaceful competition, Roman Catholic nations were bound to lose to Protestant countries if they do not reform themselves. Gabriel Monod was an ambulance driver during the war, and in his book Allemands et Français (1872) he compares the German wounded who read the Bible to the French wounded who did not read, but played cards or relished in “bawdy talk”. For Monod, the war was won by the German primary school teacher.

A major project of the Third Republic was the reform primary school education. It was felt that the future of democracy and social stability depended on it. Great importance was given to basic learning, such as reading, writing, arithmetic, and civics. The major laws of 1880 installed a Public Primary Education that was :

- free : at the end of the Second Empire, after the measures taken by Victor Duruy, two-thirds of schoolchildren enjoyed free schooling. By the law of 16 June 1881 education became free in all primary schools and “salles d’asile” (later to become infant schools) as well. The teachers’ salaries were first paid for by the municipal authorities, and as from 1889 by the State ;

- compulsory : education in a private or public school became compulsory for all children between the age of 6 and 13 ;

- undenominational : religious education was replaced by « our forefathers’ » moral and civic education. Public school staff was to be exclusively secular, and trained at the Teachers’ Training Colleges set up in every department. Their general and professional skills were to be recognised by the Brevet Supérieur and the Certificat d’Aptitude Pédagogique.

These laws meant put an end firstly, to the traditional idea that elementary schools are charitable institutions, and secondly to the fear, for some, that education would cause corruption and disorder. Moreover, university degrees were once again the State’s sole responsibility, the law having abolished those clauses in the loi Falloux (1852) whereby clergy and members of religious orders teaching in primary schools were exempted from taking exams : teachers of public and private primary schools must have passed at least the Brevet Élémentaire. Of course, degrees were not compulsory for private school teachers. Teaching provided by primary schools and advanced primary schools was quite separate from the education provided by lycées (with their own primary classes) and universities.

Secondary and higher education : were reforms inspired by the Protestants ?

A number of changes increased the efficiency of secondary education given in lycées and recognized by the baccalauréat. The opening of lycées for girls put an end to a monopoly held by religious orders for the education of girls. Sections for scientific education are inaugurated.

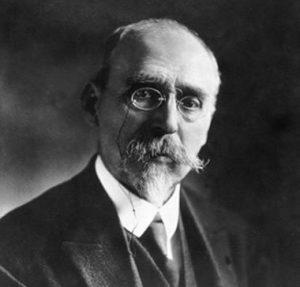

Protestants played a major part in these reforms, especially as the general context was favourable to Protestantism (see the Protestants and political power, the Third Republic). Jules Ferry was assisted by some well-known Protestants, theologians or former ministers, some of whom were to play a determining role :

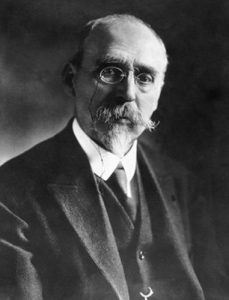

- Ferdinand Buisson, one of the leading minds behind the great Education laws of 1881-1885, set up the Écoles Normales Supérieures (Teachers’ Training Colleges) of Saint-Cloud and Fontenay-aux-Roses ;

- Félix Pécaud organized their enactment ;

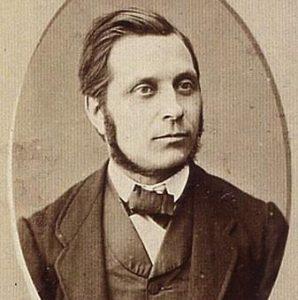

- Jules Steeg was a member of the staff of Jules Ferry who was Inspector General, at the time, for Elementary Education, and Principal of the École Normale Supérieure of Fontenay-aux-Roses.

To those names can be added those of :

- Mrs Favre, of the École Normale Supérieure de jeunes filles of Sèvres

- Élie Rabier, who for 18 years was in charge of Secondary Education at the Ministry of Education.

The part played by Protestants in the organization and the running of undenominational schools was quite significant. Seven out of the 34 newly appointed professors of education were protestant, some 12% of the authors of the Dictionary of Educational Methods were Protestant, as well as 30% of the authors of the texts chosen for the book Lectures pédagogiques à l’usage des écoles normales primaires published by Hachette in 1883. In lycées for girls about 22% of the pupils, 10% of the teachers and 25 % of the principals were Protestant.

A number of well-known faculty professors were Protestant, such as Gabriel Monod (History), Charles Andler (German), and several others. Numerous Protestants collaborated in the creation of the École Libre des Sciences Politiques established by Émile Boutmy.

The Protestants maintained their independent spirit

The vast majority of the protestant community rallied round the concept of an undenominational school, with a few exceptions (Pasteur Eugène Bersier). Although more than 1600 Protestant schools existed – most of them public in accordance with the Falloux law, and some private – the Protestants, unlike the Roman Catholics, abandoned the oversight of their schools and chose to make “a loyal experience” of the secular laws. Yet for the Protestants this secularism had to be similar to that practised in Anglo-Saxon countries : if catechism was no longer to be taught in school, religion must remain present in the general spirit and school buildings open to the representatives of the various denominations.

It has been said that the republicans made use of the Protestants because they facilitated the establishment of an undenominational school. It is true that in the early 1880s, the Roman Catholic hierarchy was violently opposed to a “Godless” school, and the Protestants, by their very presence, were of good use to the republicans, as they showed that undenominational schools were not “opposed to religion” ; all the more so since Protestants could not be mistaken for positivists (such as Gambetta, Littré, Ferry), or for free-thinkers (Berthelot, Bert). They are anticlerical, of course, but « their secularism is religious » (leur laïcité est religieuse) (P. Cabanel). Although Buisson had eliminated all religious history from the syllabus, he nevertheless insisted, with Pécaud, on man’s need for a religion : « a people do not live on arithmetic, grammar, geography or physics alone, it has superior needs that have to be satisfied » (un peuple ne vit pas d’arithmétique, de grammaire, de géographie ou de physique ; il a des besoins supérieurs qui demandent à être satisfaits). The secularism of these liberal Protestants was profoundly religious : it respected other people’s freedom. Their religion was too secular for the Roman Catholic right and their secularism too religious for the agnostic left.

From the 1890s, Protestant influence became less significant. Secularism established itself with its demand for a neutral position that does not permit any reference to religious or political choices while teaching. For Émile Combes, a former seminarist, later turned into a « monomaniac anticlerical », « the possibility of France turning gradually into a secular power of the Anglo-Saxon style – that is, anxious to preserve the neutrality of State and school among the various Churches or denominations, but not hesitating to make mention of its belief in the God of the Christians – is becoming more and more remote » (la possible évolution de la France vers une puissance laïque à l’anglo-saxonne, c’est-à-dire soucieuse de la neutralité de l’État et de l’école entre les diverses Églises ou sectes mais n’hésitant pas à affirmer sa croyance dans le Dieu des chrétiens, s’estompait, P, Cabanel).

Finally, Protestants did not hesitate to participate in the establishment of trustworthy private schools.They financed the foundation of the École Alsacienne in 1870, and carried on financing it after the Third Republic reforms. Protestants were amongst the staff of the École libre des Sciences Politiques founded by Émile Boutmy in 1870.